Our Corporate Tax Code is Unhealthy for Medical Innovation

(A version of this Health Alert was published by Forbes.)

It would be fair to say markets were blindsided by the U.S. Treasury’s 300-page plus batch of regulations that blew up the merger between Pfizer and Allergan. The deal was widely described as a so-called “inversion,” a deal whereby a U.S. domiciled company reverses itself in to a foreign firm for the purpose of reducing its U.S. tax burden.

Pfizer has been trying to invert itself for a long time. It has not been easy. In May 2014, Pfizer gave up its dance with AstraZeneca, a British-based global pharmaceutical company. The problem for a huge biopharmaceutical firm like Pfizer is that it cannot just collapse itself into a foreign shell.

As I discussed in an article published in the wake of the failed AstraZeneca deal, the newly consolidated company has to have a minimum 20 percent foreign ownership to qualify for tax inversion. That means the target has to have a market cap at least 25 percent that of the U.S. bidder – and that is only if the deal is fully financed by equity. Not that many companies are big enough to fit the bill for a company like Pfizer.

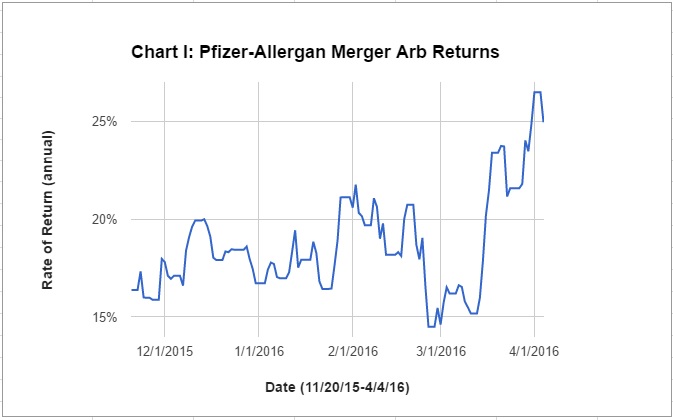

The deal with Irish-based Allergan was first disclosed provisionally on October 29, 2015, and confirmed on November 23. Since then the return to an investor who arbitraged the merger by buying one share of Allergan to exchange for 11.3 shares of Pfizer (the terms of the all-equity deal) ranged between 15 percent and 21 percent until March 17 (assuming one year for the deal to close, and taking account Pfizer’s February 3 dividend of $0.30. See Chart I.)

Not until after the middle of March did the spread widen to around 25 percent, suggesting something was indicating to investors they needed to demand a higher risk premium. Still there is nothing indicating Treasury’s regulations were leaked before being released on Monday and blowing up the deal.

I will leave better minds to wrangle with whether the new regulations are legal or not. To me, dropping these new rules into a merger that has been disclosed for over four months looks perilously close to a violation of the Constitution’s prohibition on ex post facto laws; or even a bill of attainder, because it so clearly targets Allergan.

The rules target “serial inversions,” and Allergan is the world champion serial inverter. The key to inversion is that the foreign parent can lend money to its U.S. subsidiary. The interest on that debt is a deductible expense (like all interest expense), thus reducing the company’s U.S. tax burden. The new rule significantly reduces this advantage. Treasury now proposes to ignore U.S. assets acquired by inverters over the previous three years. This rule is clearly aimed at Allergan, which is the result of a number of inversions, starting with the 2013 inversion of a New Jersey drug-maker into an Irish one.

The Administration’s frustration with inversions is sort of understandable. According to the President’s Plan for Business Tax Reform: An Update, “The Congressional Research Service identified 23 inversions since 2012, compared to only three in total in 2010 and 2011.” However, the president also understands why these inversions are necessary:

The U.S. corporate income tax combines the highest statutory rate among advanced economies with a base narrowed by loopholes, tax expenditures, and tax planning strategies

The system also is too complicated, and that complexity hurts America’s small businesses and allows large corporations to reduce their tax liability by shifting profits around the globe.

The fact that U.S. firms face a relatively high statutory rate but do not pay similarly high rates on marginal investments suggests the need for a reform of the corporate tax system that lowers the statutory rate while broadening the tax base to maintain at least the same level of revenue.

Those paragraphs could have come from any libertarian or conservative think tank! Yet, the president has chosen to disrupt the stable rule of law governing corporate transactions rather than work with Congress to solve a problem upon which there is universal agreement.

Here’s the worst of it: There is no saying how much of Pfizer’s and Allergan’s valuable management time has been chewed up trying to figure out this inversion. Uunder a low U.S. corporate tax rate and a tax code that was easy to navigate, pharmaceutical executives could seek merger partners based only on acquiring and developing sustainable competitive advantage in medical innovation.

Indeed, in one of my first Forbes columns, five years ago, I wrote about the pressure from Wall Street on Pfizer to break up because it was too big! (Followed up here.) The company can hardly execute such a plan if the U.S. government forces the C-suite to prioritize finding a foreign shore where it can find cover from punitive American taxes.

A corporation by definition cannot pay taxes. Only people pay taxes. Unless a corporation can reduce the cost of operations through technology or other process improvements, a corporation must collect the taxes it owes from…

1. Customers – by raising prices

2. Employees – by reducing compensation

3. Owners – by reducing profits.

But, in a global economy, the rate of return for owners and other capital investors is protected to a large extent because they can seek better returns overseas and when they do, we lose US based jobs.

Congress knows that it is US based customers and US based employees who actually pay the corporate income tax and the entire Payroll Tax but since they want the tax revenue and fear voter reprisal, they hide the truth from the voter by taxing the corporation and other businesses, thereby harming the US economy in the process.

For the health of the US economy and the US job market we should never tax US based production or US based labor. We should only tax US consumption.