Medicaid Expansion Does Not Create Healthcare Jobs

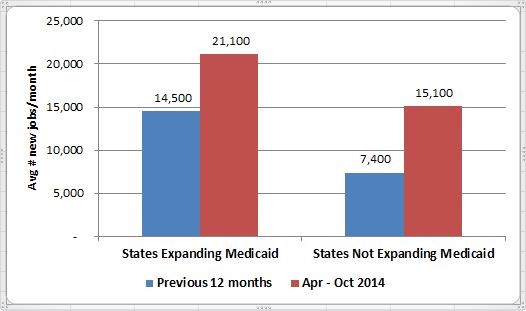

Ani Turner of the Altarum Institute has examined the growth in healthcare jobs in states which expanded Medicaid versus those which did not expand Medicaid.

This preliminary analysis shows that the recent acceleration in health care job growth should not be attributed primarily to Medicaid expansion, in part because (1) overall job growth accelerated, (2) the impact of expanded coverage on demand may turn out to be small compared to other forces, and (3) an expanded coverage effect may be present in both groups of states to a greater extent than we expected. It is important to emphasize that this is not a test of whether expanded coverage increases jobs but whether the recent acceleration in health job growth can be attributed to expanded coverage, as measured by Medicaid expansion status.

Ms. Turner’s entire blog entry is a valuable contribution to the debate over the effect of Medicaid expansion. What I found especially interesting is that healthcare job growth in the 12-months before Medicaid expansion was twice as high in the states that expanded Medicaid (14.500) than those which did not (7,400). This suggests that growth in healthcare jobs causes Medicaid expansion, rather than the other way around.

How? States with more healthcare jobs will be subject to more powerful lobbying by hospitals to expand Medicaid. Hospitals want to shift the costs of charity care off their books and onto state and federal taxpayers, which is why they lobby for Medicaid expansion. So, the extra cash flow solves a fiscal problem for hospitals but does not necessarily lead to more healthcare jobs or increased care.

Although, a caveat to this is that Ms. Turner looked at healthcare and social-service jobs overall, not just in hospitals (which I addressed in my entry on the last employment report).

There is an old theory that medical care is subject to provider-induced demand. The theory assumes… if you build it, patients will come. That is the logic behind certificate of need requirements in states where new health care ventures (or expansions) are only allowed after applicants can certify there is a need for their new capacity. In this case, I believe what we are seeing in these states is providers lobbying for expansion so they will have a financial reason “to build it.”

“So, the extra cash flow solves a fiscal problem for hospitals but does not necessarily lead to more healthcare jobs or increased care.”

This is entirely the case for physicians for whom Medicaid parity expired as of the first of the year.

Therefore, any hope that Medicaid expansion would result in more Primary Care for these patients is unlikely now.

Medicare/Medicaid payment parity hardly existed beyond the pages of the PPACA. Most states are moving away from Fee-for-Service (FFS) Medicaid to Medicaid Managed Care. Administration officials found it is difficult to boost physician fees for docs working with Medicaid managed care. The last I heard of the issue, most of the physician who actually treat Medicaid enrollees never experienced an increase.

That is my understanding as well, Devon. I am a physician but practice in Occupational Medicine, so I don’t deal with either Medicare or Medicaid (thankfully), but many of my colleagues in Primary Care do.

It is a difficult population to deal with due to lack of adequate ongoing medical care, as well as numerous social issues that lead to problems with treatment and follow up. Many physicians are more than willing to step up and help some of these people, but can only go so far with so little reimbursement.

Even in the first year, we saw little if any improvement due to the pay boost. As we’ve discussed frequently on the blog, visits to Emergency Departments are up and free clinics have converted to clinics that charge Medicaid and other payers, likely resulting in no increase in supply of services.