High Deductible Health Insurance

Question: If I asked you to point to the most obvious examples of wasteful health care spending, where would you direct me? This is a no brainer. There is nothing more wasteful than first-dollar health insurance coverage. Even deductibles as low as $1,000 or $1,500 are incredibly wasteful in many places. By that I mean that if you choose a higher deductible, the premium savings is greater than the additional expense you are exposed to. That means you can put some of the premium savings in the bank to cover the additional risk exposure (dollar-for-dollar) and still come out ahead.

Second question: When is the last time you saw an article in Health Affairs or any other health policy journal pointing out this obvious way to eliminate waste? My guess is that your answer is “never.” I’m sure you have seen articles about the hazards of high deductible insurance. Why are the journals so reluctant to focus on the benefits?

Every serious study that has ever been done on the subject has found that patients spend less on health care when they are spending their own money. The latest study by the RAND Corporation estimates that families with high deductible plans and Health Savings Accounts spend about 30% less than families with conventional insurance. And that’s with HSA plans designed by Congress. Think how much more effective the accounts could be if they were designed by the marketplace.

Further, no patient group was harmed by the switch to high-deductible insurance — not even vulnerable populations. This echoes the earlier findings of the RAND Health insurance experiment more than 30 years ago.

Ooh I’m driving my life away,

looking for a better way,

for me

In the 30-year period since the RAND experiment was conducted, a number of experiments — both within this country and abroad — have explored ways to create greater patient cost-sharing without encouraging people to forgo needed care. These include Medisave Accounts in Singapore (dating from 1984), Medical Savings Accounts (MSAs) in South Africa (dating from 1993); and in the United States, an MSA pilot program (dating from 1996), the current Health Savings Account (HSA) program (dating from 2004), Health Reimbursement Arrangements (dating from 2002), and even cash accounts in Medicaid. Many of these experiments have been subjected to considerable academic scrutiny.

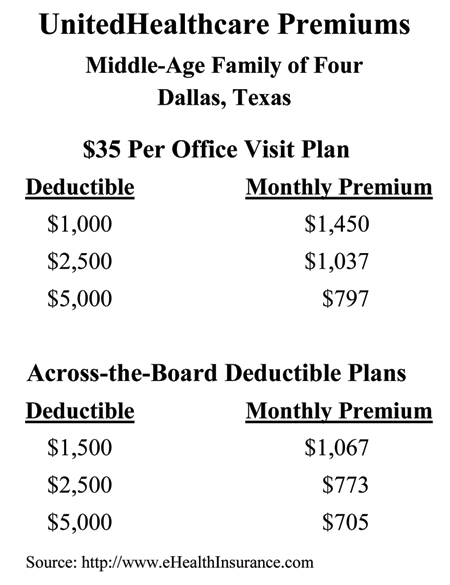

The table below shows the premiums charged by UnitedHealthcare for various policies for a middle-aged family of four in Dallas. Consider the first group of plans, with a $35 co-pay per office visit. The monthly premium for a family of four with a $1,000 per person deducible ($2,000 per family) is $1,450—or $17,400 per year.

In moving from a $1,000 annual deductible to a $2,500 deductible, the family is exposed to an additional risk of $1,500 per individual ($3,000 per family). (Note: The annual family plan deductible is twice the annual deductible per individual.) In return, they can save almost $5,000 a year in reduced premiums. In moving from a $1,000 to a $5,000 deductible, the family takes on an additional $4,000 of risk per individual (but no more than $8,000 per family). But the premium savings is nearly $8,000.

If you think about it, why would anyone buy the $1,000 deductible plan?

Gerry Musgrave and I discovered the same phenomena when we studied individual insurance premiums around the country two decades ago. At the time, I decided that as more people began to understand deductibles these oddities would disappear. I was wrong. If any reader can explain why these offers persist, please do so in the comments section.

Note: Dallas is a high-cost city and the savings from higher deductibles may not be as large in other areas. Also, the savings from higher deductibles are generally smaller for group insurance.

When I worked as a health insurance broker, one of the reasons small employers did not want a plan with a higher deductible was because they could write off the full cost of the premium on their taxes but they would have to use post-tax dollars to pay the plan deductible. S-Corps and sole proprietors can’t use HRAs to reimburse the owners tax-free for their deductible expenses; and in many cases, setting up an HRA was not cost-effective for smaller groups.

It always amazes me how little research is being done on this by the vaunted “health policy community.” Here is the greatest health care financing experiment of our lifetimes taking place under their noses, and they pay no attention.

It really is a tragedy, because there is so much we need to know — what are the optimal deductibles for different situations, the value of pre-enrollment education, what sort of information resources and health education work best, how to get provider buy-in, whether certain conditions should be exempt from the deductible, how much difference does cost-sharing beyond the deductible make?

All of these issues could help us design better programs. But we are left to grope for answers because no one is doing the research.

John, you have shown us these tables in previous posts, but they continue to be jaw-dropping in what they demonstrate. There are two primary reasons for the premium differential (and we won’t get into the complications added by virtue of guessing at exactly of what the $35 office visit benefit consists) – one is an actuarial one (at least I expect it is the case), that United’s actuaries parse the claims data between blocks of people who have these different benefits, and people who choose the lower deductible have much higher utilization of claims all along the spectrum versus people who “choose” the higher deductible. A claims continuance table for everyone combined could never produce, arithmetically, an example of where the pure claims cost differential between two deductible points exceeds the dollar difference between the deductibles – not possible. But when you split the populations, and build that into your marketing premiums, with the added loads of the administration, sales, etc., then the result reflects what the anticipated behavior is going to be. This can only be sustained, of course, so long as the higher utilizers don’t wise up and switch to the higher deductible to save on the difference, since the arithmetic you point out should work for everyone, not just people who are not high utilizers. The second reason people knee jerk to the lower deductible is the “fear of the sudden shock” syndrome that exists when people think of the worst that can happen – they need the total deductible “right now,” early in the plan year. For a lot of people, they want to avoid that situation as much as they possibly can, so they are willing to “budget” the difference in the form of premium, rather than self-insuring the “timing” risk during the year by saving that difference and then having it available if and when they actually have the “big hit.” Programs that would provide a short term financing of that “hit” balanced by a required savings program for the premium differential to pay it back (a sort of variation on “completion insurance”) would theoretically take care of this. There are HSA protector “gap” products that have been developed to do this, but they are not widely known, and are usually bundled in an expensive package with high marketing and administrative costs. An employer could certainly do it more efficiently. Sorry, this has gotten long and leaves a lot of loose ends. Thanks for your post, as always.

One reason people aren’t viewing high deductible plans as way to save money is that they expect the employer to pay all or most of the premium, regardless of the deductible level. So, in the employee’s mind, there’s nothing to gain from choosing the high deductible plan. Two things would help: (1) help employees believe that they are foregoing higher wages when the employer has to pay higher premiums, and (2) encourage employers to consolidate plan choices and only offer high deductible plans (preferably with funded HSA accounts).

All of this might be good for the consumer. What I am hearing from the physician and hospital communities are growing A/Rs.

Unfortunately, partially due to the lack of cost transparency, patients have no idea what a doctor, lab, imaging or hospital visit (particularly a hospital visit)is going to cost them.

When they receive the bill they are incredulous at the sheer size of the bill versus their perception of value and relative worth. They do not feel the same responsibility to pay a bill they hadn’t agreed to upfront to pay. Further, they haven’t had time to save for these large bills.

We need price transparency to go along with that high deductible.

I think it’s psychological. People think “If I’m paying for insurance, I want it to cover me; I don’t want to have to think about money when I’m sick.”

I had a boss who was quite wealthy; he wouldn’t hesitate to order a $100 bottle of wine at a restaurant. Once he complained about his very painful foot. I asked why he didn’t go to his doctor. He said that he couldn’t get an appointment. So I asked why he didn’t go to a different doctor. He said that other doctors wouldn’t be covered by his insurance and that he would be damned if he would pay $35 for an appointment when it was already covered by his insurance!

I think the way to overcome this is to very widely publicize the facts that John has presented.

In addition to the skewing effects of tax policy, I think Bob Blandford has captured the essence of the right answer to the question: People are irrational about money in many healthcare circumstances. Otherwise affluent people will choose first-dollar coverage even though it is obviously a bad deal for people with disposable income or savings. (I like Reinhardt’s characterization of it as “haircut insurance.”)

Part of it is just about who gets the money (It’s not unlike the example that a tax professor of mine once gave of clients who willingly spend $120 in legal arrangements to avoid $100 in taxes simply because they hate taxes–something I bet otherwise rational people on this blog might do.)

Part of it is about the emotion and security and magical thinking. The prospect of being sick or injured is scary; the emotional reaction may be globalized to be fear of even routinely predictable costs. Magical thinking makes it feel like first-dollar coverage will prevent you from getting sick or injured.

It’s just one other way that the health marketplace is different.

Thanks for the chart. I’ll use it in my class.

John, Greg…you saw the chart in my book comparing a family of 4 with a $10,000 deductible, to the same family with a zero deductible. The cost to eliminate $10,000 worth of deductible was an additional $12,600 of premium. Who would pay that? And we know that with health plans we’re only getting an 80% ot 85% return, plus paying for stuff we’ll NEVER use.

Ralph@MediBid:

That sounds like a no-brainer that even my neurosurgeon thought it was a good deal.

What we are attempting to do with Milliman, an actuarial firm, is split the population into two groups – those at $25,000-$50,000 of deductible and above, and those below.

At $25,000 deductible, the savings off a traditional plan is about 60%. At $50,000, it is about 80%.

Then, we provide a plan that is primary that builds paid-up coverage, each month, such that in 2-4 years, one could have $25,000-$50,0000 of paid-up coverage, at affordable premiums.

The only remaining premium is for the catstrophic coverage, at a 20-40% discount.

In that 2-4 year period, one buys “gap insurance” at community-rated premiums.

We should be hearing from them this week on the actuarials, and then the tweaking begins!

Don Levit

@Don,

If anything the GAP coverage should not be community rated, otherwise you’re paying for everyone else. If you have a C-Corp, just set up an HRA and pay as you go.

Funny…. Consumer Reports never makes this obvious comparison…. wonder why?

If most people bought their own health insurance, I’m sure the logic you outline would be accepted wisdom just as in purchasing car insurance you select a deductible that balances the price of the insurance with how much risk you are willing to accept.

But since most of us get our health insurance through our employers, I don’t think you can get the same savings in return for higher deductibles. I’ve been a federal employee and not a federal retiree for many years, and every open season I check out all the different options. I could only save a few hundred dollars a year by picking a high deductible option because the gov’t pays the bulk of the cost.

I assume other employers who provide health insurance create the same situation for their employees. Once folks get accustomed to full coverage with minimal deductibles it’s hard to break the habit.

This was a great summary of the psychology of the deductible issue; how consumers just have an almost tribal intent to be taken care of when sick. To make the highest and best use of the HSA feature, policy-makers should both explain the economics and supply an incentive strong enough, as a bribe, to lure people out of that way of thinking.

Wonder how far this could go if providers gave high deductible holders a discount for cash at time of service, at the level they would normally be paid by insurance. I know that some plans have a rule against that, but it seems very attractive to providers.

By the way, John, would you consider an issue devoted to a common consumer question: “Why are healthcare costs so high?” Meaning prices. This is another topic rarely dealt with comprehensively.

Wanda J. Jones

President

New Century Healthcare Institute

As a current insurance agent/broker with 35+ years of experience, I can tell you the answers are as many and varied as the comments of the 13 respondents so far. From my experiences, I long ago determined a key “deductible debate” driver was the emotion tied to becoming sick in America….not just the logic of the discourse.

Add in two other factors, those covered by employer subsidized group insurance think and buy differently than individual purchasers AND too many consumers just plain don’t have any savings outside of their employer sponsored “qualified” plans, and you begin to find the underpinnings of why high deductible plans seem unattractive to most.

Some have already answered that the logic of subsidized group coverage removes most from the effects of the premium savings to be had when promoting higher deductible plans. A sort of “why should I?” mentality is definitely at work. When an individual purchaser faces the unsubsidized, completely out-of-pocket premium lineup, he/she is far more likely to select a money saving higher deductible plan.

I’m a huge (and longtime) proponent of HSAs, yet only about 65-70% of my new business sales to individuals are for an HSA plan. The remainder are non-savers (or their money is tied up in “qualified” employer plans) OR, they are simply adverse to the potential and timing of the “shock claim” described by H D Carroll (above).

As proposed in another answer, far too many are more satisfied by the “budgeting” effect offered by the higher monthly premiums with the lower deductible/copay type plans.

It confounds me, even after you can show how the combined premium and tax savings associated with an HSA will better their position. Even after showing them they will get the carrier’s discounted pricing for provider fees and Rx costs (Wanda Jones, take note…it’s already taken care of in most PPO situations during the deductible accumulation phase).

I shudder when thinking about the amount of money that is tossed away and only purchases “sleep” insurance. If consumers would just realize what they could do for their retirement plans with the savings from a HDHP (not to mention the recapture of the lost opportunity costs), we’d all have a better chance of helping them change their points of view.

Ralph:

The community rating of the gap coverage is for 2 reasons:

1. It gives higher claimants a price break on the cost per thousand.

2. If we form a 501(c)(4), one of the primary tenets would be community rating. The Blues going to experience rating from community rating was a huge factor in the demise of their federal tax-exemption in 1986, with the passage of IRC section 501(m).

This part of the program, the community-rated gap coverage could be funded by the employer. The paid-up monthly contributions would be an employee-pay-all arrangement.

In any case, these would be individual policies which they will take intact with them wherever they go.

Jerry:

I am in agreement with you what the employees could do for their retirement savings by reducing health insurance premiums.

Our m to place a percentage of the health insurance savings in their 403(b)s. We think a for-profit life insurer who is heavily into that business will be willing to let us form a 501(c)(4) subsidiary, so that new reserves will not be needed – even from government loans!

Don Levit

Jerry B, your experiences with clients is typical, and in my view it is simply a process. Put another way, attitudes on healthcare and insurance have developed over many decades and are firmly entrenched. The HSA concept (and consumer directed healthcare in general) is a relatively new approach, and has been handicapped by a government hostile to the notion of personal responsibility. In fact, the only way we were able to even have HSAs was to bring it in the back door through the Part D Medicare legislation.

In spite of this HSAs have had relative success, but in order for Consumer Directed Healthcare to really mainstream there will have to be political involvement (starting with the demise of Obamacare). If we have a new government in January perhaps people who have a clue such as DeMint and Coburn will be in a position to bring focus to legitimate reform. That will force honest discussion and media attention to the realities of healthcare financing as John Goodman illustrates above.

@Don Levit: Your product confuses the heck out of me and I (try to) earn a living studying these things.

There’s not much use having a high-deductible plan that’s even more confusing than what we already had!

I agree with the comments on price transparency. People are scared to bear any significant deductible because they don’t believe that they can master the spending below the deductible. That’s not true for other types of insurance (auto, et cetera).

Although I am a huge fan of consumer-driven health care, I also thhink we are nowhere near “consumer-driven” health care. As Dr. Goodman states, this is Congressionally designed CDHC, not market-designed CDHC.

The fact that Congress effectively outlaws long-duration health plans (as discussed by Prof. John Cochrane in the WSJ (“What to do on the day after Obamacare” 4/2/12) means that we are stuck with annual deductibles.

What kind of sense is it to define a deductible by the number of days it takes for the earth to revolve around the sun? In a market-driven system, co-pays and deductibles would be customized to health status, not the calendar year.

Under Obamacare, “previentive care” is “free”. So, a friend of mine had a “free” annual physicial. Because of an indeterminate pap smear, she had to have another one for a cost of hundreds of dollars. If anything, it should have been the other way around.

John Graham writes

“In a market-driven system, co-pays and deductibles would be customized to health status, not the calendar year.”

John, can you explain how you envision this in practice?

John:

The actuaries at Milliman were confused for the first couple hours of our first meeting.

Then, in the last hour, they got it!

I believe the problem lies more within our culture than you or Milliman individually.

As the actuaries testified “This is a cutting edge plan, one unlike we have ever seen!”

I can assure you it is more simple than any other plan out there I have seen.

If you want a bit more explanation, feel free to E-mail me at donaldlevit@aol.com.

Don Levit

I can try. Do you agree that a deductible that ticks over every year makes no more or less sense than one that ticks over every month or every five years?

How can that do the best job of making me optimally sensitive to the price of a medical good or service?

Suppose I am chronically ill, such that I need to use bottled oxygen – which I choose as an example because that is one of the Durable Medical Equipment (DME) categories often identified as too expensive. Such a patient should experience different co-pays for different providers, but I don’t think a deductible makes sense at all.

Suppose I’m suddenly struck with cancer: What good does a deductible do me? Instead, the insurer should either cover all the costs or pay a fixed amount for me to go to another insurer who specalizes in covering people with my type of cancer.

If an insurer “subsidises” a certain drug, will that reduce hospitalization? If so, the co-pay should be zero. But there is no general theory: It depends on the condition and the therapies available, which always change.

I doubt the large group insurers can master the complexities of this. Each disease condition will have its own unique characteristics that will determine how “consumer-driven” it is.

In a world of health-status insurance, as described by John Cochrane, this would result (perhaps) in hyper-specialization of insurers.

But that is predicting the future, which is a dangerous game!

My own experience in selling health insurance is that at older ages, the price spread between low and high deductible plans is not as exciting as Dr. Goodman suggests.

A $250 deductible plan for a 60 year old might cost $600 a month in an average market.

But a $5000 deductible plan still costs close to $450 a month, last I checked.

So the consumer only saves $1,800 a year, in exchange for which he has $4,750 more in personal liability.

My gut instinct is that a $5000 deductible plan should be close to free, given how seldom it will pay clains.

Actuarially I can understand the tightness of premiums. 60 year olds do generate some very large claims, and a 60 year old who really wants to buy insurance is kind of a suspect risk in the first place.

But emotionally, a high price for high-deductible insurance still feels like a ripoff.

And if I feel this way, with a fair amount of industry knowledge, just think how the average person feels.

I see what you are getting at John. You are right that it creates great complexities from an actuarial standpoint, especially with regard to moral hazard. But in keeping with your train of thought, I am intrigued with the idea of more emphasis on coinsurance and less on front end deductibles. If the idea is for the insured to always have “skin in the game”, there are other ways to get it done and not confuse the poor insurance carriers.

For example, instead of a $5000 deductible, then 80% up to an “out of pocket maximum of say (another) $1,000, perhaps a $200 deductible (just to avoid nuisance claims) and then a 60% benefit up to an out of pocket maximum of $10,000. At least the deductible is a non factor, and if all was right in the political world this type of plan could qualify as HSA eligible. Just sayin’.

I know that ‘European’ ideas are not popular on this blog, but let me offer a European perspective anyways.

Which is that deductibles and coinsurance are a cowardly and cruel way to control health care prices.

In Germany, France, or Japan, the government essentially decrees that the price of an MRI shall be $250.

In America, we do not have the political will to do this, so hospitals and clinics are allowed to charge $2500 if they can get away with it.

We then put high deductibles into our insurance policies so that individual patients will have to confront the $2500 charge, and I guess get so mad at it that they will shop around until they find a provider who will take $250.

To a European this shopping around is a monstrous waste of time, plus it harms the doctor-patient relationship, plus a lot of patients are economically harmed because they don’t or can’t shop around.

My post is written in a rather breezy style but I am serious. A more professional phrasing of my anti-free market ideas can be found in the writings of Uwe Reinhardt and Joseph White.

Bob Hertz, The Health Care Crusade

John:

The design of my plan is intended to pay very large bills intermittently, say every 4 years.

It is not good coverage for chronic diseases which require fairly large benefits each year.

Philosophically, we are not responsible for the size of the medical bills.

That is determined outside of our control.

We can attempt to whittle them down, of course.

Insurance is most effective at paying large bills on an intermittent basis.

I believe one should always have some type of co-pay or co-insurance, for if not, the person tends to think he is in this game of life alone.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Instead of complaining about what the insurance does not cover, people should be grateful for what it does cover, particularly if you look at benefits paid versus premiums paid.

Again, it is not our fault a 10-day hospital stay may cost $200,000. It is our responsibility to attempt to pay off the bill to the best of our ability.

Don Levit

“In Germany, France, or Japan, the government essentially decrees that the price of an MRI shall be $250.”

Bob, do realize that price controls have been tried in all manner of economic scenarios and they never ever are successful? Had there been “price controls” on imaging technology before the advent of “MRIs”, MRIs would have never been invented.

Healthcare reform is about long term workable solutions, not political expediencies. Insofar as the European distaste for “shopping around”, perhaps that is a clue for the economic mess that most European countries find themselves. I’ll pass on emulating that philosophy.

From Frank (April 11 at 9:24): “Had there been “price controls” on imaging technology before the advent of “MRIs”, MRIs would have never been invented.”

So does this mean that you believe that all the rest of the world (with their price controls) are free riders on the prices paid by US private insurance-premium payers and US taxpayers (supporting public insurance programs)? Are you really suggesting that it’s only the US that provides the profit margin sufficient to induce innovation?

I find it hard to believe (although I could be convinced with evidence (which cannot be produced since there’s no transparency about pricing decisions by device or drug manufacturers) that the profit margin built into the fixed prices of industrialized nations’ health care systems (not including the US) is insufficient to produce innovation.

This premise dubious given the extensive intellectual property protections (patents and, increasingly important, exclusivity protections) that such manufacturers enjoy. And it’s really hard to believe when the innovation is a near-replication of the previous products (aka “me-too” drugs and devices) but enjoys the same protections and pricing advantages that the true innovator enjoys.

But I guess it comes down to the default setting of what we believe without any true evidence. I believe that we can reward manufacturers less without affecting incentives. You apparently do not. (Manufacturers concur with you, but they and their studies have some serious conflict-of-interest questions about the outcomes.) Unfortunately, that fact-free decision (which the US government appears to share with you) is worth billions and billions of dollars.

Where are the free-market data hounds when we need them?

My apologies. I should proofread my comments before submitting them.

The sentence in the previous post that reads,

“This premise dubious given the extensive intellectual property protections (patents and, increasingly important, exclusivity protections) that such manufacturers enjoy.”

should have read: “This premise seems especially dubious….”

My mistake.

Tim, you wrote

“I believe that we can reward manufacturers less without affecting incentives.”

It seems you have changed the subject from the question of free markets vs. price controls to whether or not the government should be providing tax incentives to certain industries. That is a completely different question, and although certainly part of the economic discussion it has nothing to do with my comments on price controls.

In answer to your first question I would say absolutely, at least in terms of the general premise that “managed economies” are free riders on the backs of free market economies. This is not to say that there has never been a useful product that has originated in a controlled economy, although I am hard pressed to think of any not related to the military.

Perhaps I miss your point.

Re: frank timmins April 11, 2012 at 2:24 pm

Sorry I was not clear. I am NOT talking about tax incentives.

I’m talking about the high market prices that manufacturers extract from the US and its citizens when our patients, their commercial insurance companies, their ERISA employers, or (in the case of Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) their public insurers pay for the new products (like the original example of MRIs). That’s what I meant when I said I believe we can reward drug and device manufacturers less without affecting their incentives to bring new and better products to market. That is to say, I believe we could control drug and device prices in the US and there would still be lots and lots of innovation.

Again, I acknowledge that I cannot prove this point. As long as there’s no transparency about pricing policy from the companies and as long as intellectual property protections provide monopolies, no one knows where the tipping point is. But our continued assumption in the US that the drug and device companies will stop innovating if they are required to charge a penny less than they want to charge is costing us all billions and billions of dollars–all on an unproven hypothesis. [I will say that I think that the suggestion that these otherwise successful and shrewd companies are taking losses when they sell their products in Europe is laughable, but I can’t prove that what makes me laugh is actually wrong.]

I was also trying to say that the intellectual property protections of extended patents and market exclusivity in drugs and devices have compounded this effect, allowing manufacturers to extract uncontrolled monopoly profits from US patients and US insurers (private and public) for a longer and longer period of time.

As for your answer that there have been no useful products originating in a controlled economy, I would reply that I think that that’s no longer an answerable question or even a meaningful question. Drug and device companies do not exist only in the US or Europe or Asia anymore. They exist both everywhere and nowhere. Their innovations will “take place” wherever FDA regulation (or the equivalents in industrial nations) says that the innovation should take place for expediting drug- or device-approval processes. If the US FDA were to accept trial data from Papua New Guinea, then the innovation would take place there. The fact that many trials take place in the US reflects the fact that FDA may give preference to domestic trial data as more reliable.

And, given that the drug company scientists may be sitting in Zurich or Paris or London, it’s just not possible to say where the innovation actually is taking place. But certainly the fact that Switzerland, France, and the UK have drug price controls in their insurance systems is not driving companies to move all their smart scientists to the US to “innovate here.”

Finally, I do have other views on tax incentives, but that’s not what I meant to be talking about here. Sorry I was unclear.

TMW

Whoa, whoa, whoa. Intellectual-property law does not grant monopoly. Monopoly describes a market, and patents protect products from being copies. They do not prevent competitors from entering the market. If they did, there would be only one lipid-lowering drug, for example.

The recently slow pace of pharmaceutical innovation is largely the fault of the FDA’s foot-dragging and risk-aversion, not patents.

John’s comment on the FDA actually preventing competition is very interesting. I am surely no expert on big pharma so I am sure willing to listen.

I would have to ask Frank if he or a member of his family has had to do any serious medical shopping. I guess i am a classic American in that I dislike haggling anywhere. But haggling with doctors is humiliating, plus it destroys the good will that you need to heal.

I should have been more precise than to describe German or French health care as price controls. What I think happens is that associations of doctors and hospitals meet with insurers in a kind of massive collective bargaining that sets prices based on an overall budget.

That is not pure price control, and I see no evidence that it fails.

As for Japan, they do have something close to pure price control, and I think Frank is plain wrong. It is not a massive failure.

John, you’re generally right that first dollar, even $1,000 to $1,500 deductible health insurance is wasteful. MediBid has found a way to engage consumers even in low deductible plans with benchmark, or defined benefit plans. I have engaged many employers this way where say an employee needs a knee replacement, and the median price is $15,800. The employee pays extra if they chose a knee replacement that costs more than $15,800

Bob writes, “I would have to ask Frank if he or a member of his family has had to do any serious medical shopping. I guess i am a classic American in that I dislike haggling anywhere. But haggling with doctors is humiliating, plus it destroys the good will that you need to heal.”

Indeed, it seems that semantics are involved here to some extent. I’m not sure what you mean by “serious medical shopping”, but I have many personal experiences with medical shopping. Some were very frustrating, but not for the reasons you suggest. It is not about “haggling” in the sense of someone buying a used car or a sombrero in Tijuana. Rather it is about pricing transparency and true competition, which brings into play your other comment.

The process you describe of doctors and hospitals meeting with insurers and setting prices based on some sort of budget is precisely the overriding problem. Do you not recognize that the most important element of the economic process is excluded from this “agreement”? That would be the customer (patient). I believe this is indeed price control, In this particular case it is not the government, but it is still third parties fixing prices without the input of the consumer. And no, it doesn’t and hasn’t worked well at all. We have been experimenting with it in this country for decades (third party contracting), and you see where it has led us.

I think that my exchange with Frank shows the gulf between left and right on health care.

To the left, where I mainly reside, the consequence of high deductible insurance is that people will decide not to see the doctor or buy drugs if they are broke, or if the price seems too high.

This will cut down on some frivolous care. But it will also lead to terrible health consequences in some cases. Anyone in medical practice can find many many examples, in both young and (before Medicare) the elderly.

There is probably a workable solution, which would involve some services being available to anyone, either free or highly subsidized. The care of young children should be next to free, accidents and injuries should be next to free, etc.

When generous employers go to high-deductible insurance, they usually “seed” the HSA accounts with some employer money, so that the patient is not overly stingy on their preventive care. I have no problem at all with that. It combines the economic good sense of high-deductible insurance with a little real world compassion.

But believe me, in most parts of the insurance market, people are forced into high deductible plans and they have no HSA whatever.

Show me a way to minimize the disasters of individual choice and I will gladly move rightward on this issue.

@Bob Hertz

Check out my website, you might find that it answers your request.

Bob Hertz,

Your comment raises a whole lot of issues. Let’s start with this — The very idea that you, Bob Hertz, would know better than I, Greg Scandlen, when I should go to the doctor is offensive. A few months ago I missed a doctor’s appointment because I was waiting in his office for 45 minutes past my appointment time. I got up and left. Is it your job to intervene in that decision?

Next, a lack of money is always a problem. But it is every bit as much a problem when paying health insurance premiums as it is when paying directly for a health service. If someone doesn’t have the money to pay for a doctor’s visit, they probably don’t have the money to avoid having to pay for the doctor’s visit, either. In fact, we get FAR more value from spending a dollar directly on the doctor than we get from spending that same dollar on an insurance premium.

Yes, I know — our employers “give” us the insurance but we have to pay for the doctor directly. But surely you know the employer doesn’t give us anything. Every dollar they spend on insurance premiums is a dollar we don’t get in wages. That is the main reason wages have stagnated so much in recent years.

I’ll leave it there, but I appreciate this opportunity to have a civil conversation.

Greg,

You bring up a good point abut employer contributions. Since 1954 when the IRS made contributions pre-tax, employers have shifter growth in overall employee compensation from salary and towards benefits, which is why benefits inflation greatly outpaces wage growth and cost of living. I wrote about that in MediCrats. But that is changing now. Employers have caught on to the fact with the MLR, that only 80% of their dollars are paying for medical care, and that “insurance discounts” are not as low as they are getting by paying physicians directly, as they do with MediBid. I think it’s about to come full circle Greg.

Bob, I agree there is probably a workable solution as long as left leaning people are truly interested in finding the solution (like yourself). Unfortunately with too many others it is not about finding solutions. Rather it is about using the healthcare issue to gain political and economic control over the American citizens, and I am pretty sure you who falls into each category.

Aside from the editorial (sorry), I agree that there needs to be some government subsidy. The question is how should that subsidy be organized, and who gets the subsidy? There is a difference between people who need a subsidy and people who are unable to “manage their lives” for various reasons (age, disability, etc.). We simply must stop attempting to “top down” manage the economic business of individuals,other than those who truly cannot manage themselves.

If people would recognize this then there certainly are ways to solve healthcare problems.

Bob:

Regarding high deducyible health insurance and the underlying coverage:

As my plan is currently designed, the underlying paid-up coverage starts from dollar one.

But, the premium for the coverage gap, up until the catastrophic beginning of $25,000 is based on assuming the underlying coverage IS the deductinle.

For example, a person has $10,000 of paid-up coverage. The next $15,000 of premiums is community-rated assuming he has a $10,000 deductible.

Don Levit

Don’s program sounds terrific. I am left wondering how much it costs to build up $25,000 of paid up coverage. Seems like it would cost close to $25,000.

Let me go back to medical shopping.

I have no problem with shopping for drugs, lab tests, and medical equipment.

Hooray for Walmart and their $4 drugs, hooray for Quest Diagnostics and their $35 lab work, etc. Keep health insurance away from these services, please!

The key to good shopping is to have some disposable income. That sounds kind of crude, but it really goes to the heart of where I am going in my posts.

People who have no income in America can get Medicaid in most states, and under the ACA will get Medicaid in greater numbers. They don’t get many choices but they do almost always get care.

People with high incomes and savings can also do well with medical shopping and high deductible insurance. Shopping is fun when your charge cards have high limits and low balances.

My concern is for those people in the middle who have layoffs, divorce, more kids than they can handle, etc. For them, high deductible coverage feels like no insurance at all. This is the group that has bad teeth, untreated diabetes, etc.

I would agree with Greg and Frank and Mike Tanner and others that a trilliion-dollar single payer plan is not the way to help the group above. (It would help them, but be a national disaster very shortly.)

The solution may not involve health insurance at all. It could involve medical food stamps, which Thomas Saving has brought up. You would get what amounts to a voucher, say $500 per child per year. This is much cheaper and more targeted than first dollar insurance.

The vouchers would be good at any private clinic, and the clinic could charge a little more if they wished to. The food stamp program does not cripple the nation’s grocery stores with rules and regulations.

I am not sure how to establish eligibility for the vouchers. I dislike any federal program with a ‘cliff’, where you get a nice benefit at $29,000 of income and lose it at $30,000. But that is a detail that can be worked out.

Bob:

we should be meeting next week with Milliman. The hope is 2-4 years, based on contributions between $100 and $400 per month.

More details next week.

Don Levit

Re. Hertz’ voucher proposal…. would these be like food stamps which are widely resold and turned into cash?

From an actuarial perspective, much of the cost differential may hinge on whether or not the insurer segments the risk pools by deductibles that tends to reflect a self selection of good risks purchasing high deductible plans (good health, higher income, more educated).

Insurers that cross subsidize plans will not show as large a premium differential. These type of internal ratings are never disclosed to consumers and as such many purchasers of HSA eligible plans never get the full benefit of their lower claims experience. This is also why many HDHPs are not as favorably priced for initial sales.

Keep in mind that insurers are not all that interested in lower revenue income from lower premium products (nor are agent interested in lower commissions). John, another key to why your prediction of closing the deductible/savings gap did not come true is that insurance is more sold than bought. The market is not even close to an educated consumer free-market where an economist and economic models would see financial discontinuities closed over time.

Ron:

In our dealings with Milliman, we truly want to give the actuarial price break, the larger the deductible.

As I have tried to explain, the underlying paid-up plan pays up to the ever-rising deductible.

With no cross subsidization, I am concerned those with lower underlying paid-up benefits and correpondingly lower deductibles will be “overpaying,” whole those with large paid-up balances and higher deductibles will be underpaying.

We are trying to address this with community rates up to the catasreophic point of $25,000.

Any thoughts?

Don Levit

@Ron,

Good point, and that often seems self evident by the rates. In states like CA, where HDHP’s are overseen by the DOI, and PPO and HMO plans are overseen by the department of managed care, do they still cross subsidize?

I agree that insurance is sold rather than bought. However, that’s true for lots of financial services. It did not stop the rise of price competition.

For example, if you want to sit across the kitchen table from an insurance agent selling you a variable annuity, you are free to fall for it. However, you can also buy term life online from a highly creditworthy carrier for a reasonable premium.

Similarly, if you want your savings devoured by management fees, you are free to go to a full-service broker or actively managed mutual funds. But if you want not to waste your money, you can go to a discount broker and invest in plain-vanilla ETFs or indexed mutual funds.

People are free to get gouged if they want. However, the government should not force the rest of us to be gouged too!

John,

I agree on principle with you. Some financial professionals provide a lot of value to earn their fees, some simply accept a commission. Likewise some clients are happy to manage their own affairs, while others prefer the services of a professional and do not mind paying for that.

Having said that, a one-size-fits-all approach, where everyone is charged the top level of service when not everyone needs it is an abuse of legislative authority.

I relish, lead to I discovered exactly what I used to be looking for. You have ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

Great discussion. Disappointed that it stopped so abruptly. I am currently looking for an aggregate maximum deductible amount for the whole company or membership companies, I am putting together a product that will blow the market. Any further comments on Gap aggregate coverage will be appreciated. I hope some people are still reading this column.

Mine perspective is from a solo medical practice vantage point. Patients typically will not pay their medical bills during the so called deductible season. This season strategically falls during and after the major winter holiday season when insurance companies know people are over spending on foolishness and will stubbornly refuse to pay for that from which they derive no immediate gratification, especially if they deem the cost to be particularly high. By remaining in solo practice, we are actually saving patients money, but they don’t see it that way. During deductible season, i have had to lay off employees and draw from lines of credit to pay our bills. If I try more enthusiastically to collect from the patients who owe us money, I’m a monster who does not understand Christmas and a million other silly expenses people can name. The lesser educated patients will tell me that healthcare is their inalienable right and that they should be getting it free of charge. Believe it or not, I also have people asking to be put on a six month payment plan for bills that are under $200.00. I would like to see the end of the traditional deductible season. I believe that patients who have purchased insurance have the right to receive the insurance company’s contracted write off on all of their bills and that the deductible costs should be spread out over the year. That way, the six month payment plan is already built into the bill. Yes, more people would go to see their doctors during the winter months, but more frequent office visits usually save money as far as people with chronic disease processes are concerned. If we are able to see these people more frequently, we are able to intervene before an issue becomes critical enough to require emergency hospital admissions. I hope someone comes up with better solutions, soon, or we’re going to have to fold the way so many other practices have, and people like Greg will have to wait even longer than 45 minutes to see their doctors … or maybe they’ll just have to end up going to see one of the claims processors for their insurance companies, since many of them think they are more qualified to practice medicine than most doctors.