Why Can’t The Market for Medical Care Work Like Cosmetic Surgery?

Americans see their doctors more than 1 billion times a year ― and spend nearly $300 billion on physician services ― but they rarely discuss the price of a given service with their physicians in advance of receiving treatment. It gets worse. Although only about 10 percent of health care expenditures are spent on physicians’ services, doctors are the gate keepers to virtually all care that is provided to patients ― including MRI scans, lab tests, hospital admissions and surgeries. Yet doctors rarely provide a list of prices for goods and services they provide or discuss the prices of the procedures they order. Patients don’t bother to shop for medical care, and doctors don’t advertise their prices because nearly 90 percent of patients’ tabs are paid with other people’s money.

However, when patients pay their own medical bills, they act like normal consumers ― comparing prices and looking for value. And when patients act like prudent consumers, doctors who want their patronage must respond by competing on prices, convenience and other amenities.

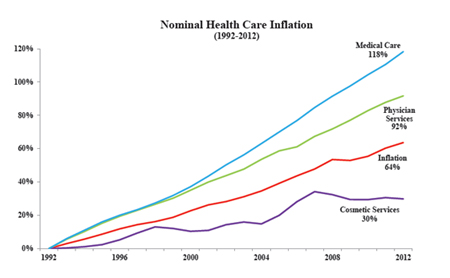

Consider cosmetic surgery, one of the few areas of medicine where consumers pay out of pocket. The inflation-adjusted price of cosmetic medicine actually fell over the past two decades — despite a huge increase in demand and considerable innovation [See Figure]. Since 1992:

- The price of medical care has increased an average of 118 percent.

- The price of physician services rose by 92 percent.

- The inflation rate, for all goods and services, as measured increased by 64 percent.

- Yet cosmetic surgery prices only rose only about 30 percent.

The price of cosmetic medicine was held in check by a variety of competitive forces: Doctors who perform cosmetic services quote package prices, and generally adjust their fees to stay competitive. The industry is constantly developing new products and services that expand the market and compete with older services. As more cash-paying patients demand procedures, doctors rush to provide them. There are few barriers to entry in cosmetic surgery. Any licensed physician can enter the field.

Entrepreneurial physicians are also on the lookout for new ways to market their services. Consider the ubiquitous deal-of-the-day emails, where Groupon and LivingSocial offer goods and services to subscribers at greatly reduced prices. These daily deal promoters offer numerous medical-related services, including Botox, corrective eye surgery, dental teeth cleaning, teeth whitening, laser hair removal, laser facial resurfacing, cosmetic fillers, spider vein and brown spot removal at highly discounted prices. This defies the conventional wisdom that a doctor would never advertise a bundled cash price — much less extend the offer to hundreds of thousands of random people sight-unseen. Yet the offers land in millions of email inboxes every day, and competition is fierce.

Consider botulism toxin injections, such as Botox and Dysport. According to surveys by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the average fee to administer botulism toxin was $369 in 2012, compared to $365 a dozen years earlier in 2000. Groupon and LivingSocial have occasionally offered Botox deals for as little as $99, with $149 quite common.

Another competitive service is laser skin resurfacing, which cost about $2,556 in 1996, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Physicians began offering less-invasive, fractional laser resurfacing that reduced recovery time. The cost of fractional laser skin resurfacing fell to $1,113 by 2012. Yet, couponing websites have offered numerous laser resurfacing deals for only $299. One Dallas-area Med Spa even offers this service, available with a one-year membership, for as little as $149 — a mere fraction of the cost elsewhere.

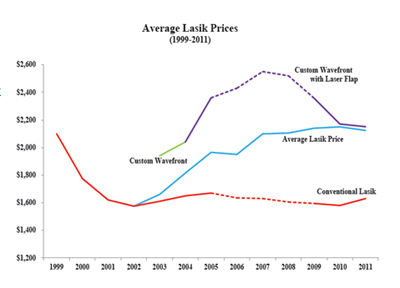

Wherever there is price competition, quality competition tends to follow. Take corrective eye surgery. From 1999 (when eye doctors began performing Lasik in volume) through 2011, the price of conventional Lasik fell about one-quarter due to intense competition. [See Figure] Eye surgeons who wanted to differentiate themselves from other surgeons, and charge more, began to provide more advanced Custom Wavefront Lasik technology using IntraLase (a laser-created flap). By 2011, the average price per eye for doctors performing Custom Lasik was about what conventional Lasik had been more than a decade earlier; but the quality is far better. Occasionally an eye surgeon will offer a daily deal at half this price.

through 2011, the price of conventional Lasik fell about one-quarter due to intense competition. [See Figure] Eye surgeons who wanted to differentiate themselves from other surgeons, and charge more, began to provide more advanced Custom Wavefront Lasik technology using IntraLase (a laser-created flap). By 2011, the average price per eye for doctors performing Custom Lasik was about what conventional Lasik had been more than a decade earlier; but the quality is far better. Occasionally an eye surgeon will offer a daily deal at half this price.

One criticism skeptics often voice in discussions about fostering patient consumerism is that a patient having a heart attack is not in a position to shop for the cheapest cardiac care from the back of an ambulance taking him to the emergency room. Few people would disagree. But only about $1 out of $20 is spent on patients who enter the health care system through the emergency room door.

Consider the experience of an insured patient whose doctor orders an abdominal CT scan. Receiving this service at a hospital outpatient department could cost the patient (or her health plan) nearly $3,000 depending on whether the patient’s deductible has been met. Yet this same service is available outside the hospital at a medical imaging center for prices that are often 85 percent less. Few health plans provide the tools for enrollees to compare prices and few patients have an incentive to ask about prices.

Doctors and hospitals don’t quote prices and don’t compete on price because most patients are largely insulated from the adverse effects of not making price comparisons and acting like consumers. Both economic studies and common sense confirm that people do not shop carefully and prudently when someone else is picking up the tab. The contrast between cosmetic surgery and other medical services is important. One sector has a competitive marketplace and stable prices. The other does not.

The medical marketplace should work more like the market for cosmetic surgery.

Study: The Market for Medical Care Should Work Like Cosmetic Surgery.

The typical response when people talk about lasik price stability is that you cannot shop for medical care on the way to the emergency room. I don’t think there is any question. It’s also hard to shop for automotive repair when being towed to the dealership. Yet, the market for auto repair is competitive — if not sometimes annoying.

Most medical care is not initiated with an ambulance ride. I’ve hard that only something like 4% or 5% of health care expenditure is on people who were brought into the emergency room.

Among the cosmetic procedures I reviewed, the ones with the highest degree of price stability were those that could be (almost) viewed as commodities and performed by trained aestheticians in a spa that was only nominally supervised by a medical doctor. Consider Botox, the price in 2012 was within a dollars of the price back in 1999.

“However, when patients pay their own medical bills, they act like normal consumers ― comparing prices and looking for value.”

This is also true in general, self-interest motivates us to achieve the greatest value. This is the primary reason that government is notoriously wasteful – the incentive structure isn’t appropriate.

The problem of not seeking the lowest price is even worse than simply using “other people’s money.” If John Beresford Tipton, Jr. offers to pay for something for me, I will probably make a prudent choice. In the case of insurance, though, I think that I have prepaid, so I want to extract the most value I can from the insurer. Any small perceived increase in the worth of the service will justify a huge increase on what I’d be willing to have the insurer pay on my behalf. That gives me an apparent higher return for my premium dollar–a factor not present in a simple OPM situation.

I think you’re correct that many people equate spending by their insurer with value for their premium dollars. It makes sense, we certainly wouldn’t want to think we’re spending money on premiums and getting nothing of value in return. However, this perverse incentive inflates medical claims.

The Doctor’s concept of price shopping and procedure education and discrimination is sound, but he misses the simple fact that people do perform these functions … through their proxies … insurance companies and Federal agencies. The proxies are the ones that keep tabs on costs and bargain with the doctors for the uninformed masses.

It looks like the CA exchange plans are bully on patient responsibility, with $2000 deductibles and multiple copays. Reduces govt. spending and places more responsibility on the consumers. Go … ACA.:)

http://blogs.kqed.org/stateofhealth/files/2013/02/CC-Standard-Individual-Benefit-Plans.jpg

@Big Al

No sir, the insurance companies and federal agencies are most definitely “not” the “proxies” for patients’ interests in healthcare cost and quality. They are working in the interest of their own “Macro” economics, not those of the individual patient. And long as these methods for managing costs prevail those “masses” will continue to be “uninformed”.

I must say using terms like “uniformed masses” takes me back to my school days when the Soviets were denying their population consumer goods in order to compete militarily with the West, and China was in the midst of its “Cultural Revolution” and “re-educating” its “masses”.

With all due respect, I must disagree. Insurers and Agencies watch and negotiate prices with providers, do they not? They are implementing quantity-muscle free market practices (since Doctors have the choice to play or not). I pay insurers to use their education and influence … thereby increasing both our bottom lines.

Big Al, you don’t seem to connect with the notion that “third party” interference in healthcare dooms the chance of economic efficiency so let’s try this scenario.

Say you want to build a house with a certain number of square feet on a certain lot. You ask for a “turn key” quote from a home builder to build this house and he comes back with a price of say $500,000. You decide that you only want to pay $350,000 for this house. Do you:

1) Negotiate further with the home builder, or

2) Go find another home builder, or

3) Tell the home builder you are only going to pay $350,000, and that he must build it or there will be unpleasant consequences for him.

Guess which option you have chosen for your healthcare.

I left a little for the imagination here Big Al, but on second thought I should be more clear. In the 3rd scenario what do you think is going to happen to the quality of this home you are having built? Do ya think there may be a few er….shortcuts taken?

The builder can cut as many corners as he wishes, as long as he follows code (ACA/Legislative System) and warantees his work (Judicial System)

So unfinished cabinets, plastic faucets, and carpet that lasts 6 months would be AOK with you? None of these are a problem with building codes or are warranty issues. And there are hundreds of other “short cuts” that you would not even know about.

Think about that when you are visiting that heart surgeon who has twice as many patients as he can handle because he needs to see that many to make it worth while to practice.

This is where the measure of quality bumps against the staircase of opulence or perfection. My progressive side simply needs a roof over everyone’s head, but my conservative side says that if my neighbor needs a gold plated toilet seat, it’s on his dime. National health care should only be the guaranteed and warranteed roof. Free market is for the parquet floors and crown molding.

Let’s be realistic here Big Al. We are not talking about “opulence or perfection”. We are talking about decisions being made between the physician and his patient vs. between the physician and an insurance company or government agency. This is not about “gold plated” hysterectomies.

That said, there is not a problem with your “progressive” inclination to have a “roof over everyone’s head”. I doubt you will find an argument to that desire anywhere on this site. Perhaps you should consider other ways to achieve that end besides diluting the healthcare quality for the entire population.

I do understand that when an insurer negotiates (dictates) what they will pay a doctor for procedures … and … holds the doctor to certain levels of performance, the doctor scrambles to see where reasonable cuts can be made. I agree that this is not optimal (gold plated) service but every trade out there is going through the same conundrum. Like it or not, people do like insurers to leverage doctor bills and if one is going to stay in the game, one has to adapt.

Ideas: I would make health care providers exempt from tort, with the exception of gross negligence, in which case criminal proceedings would be a litmus test. Malpractice Ins. could be a thing of the past.

I would invoke ‘Palin’ Rules (killing grandma) which would restrict public funds for high cost procedures based on age, health, and survivability. No more Medicare open heart surgeries for 90 year olds or premium care for stage 4 cancer. Survivability at any cost (to the public) must be addressed.

All players have defendable positions in this game of health care.

“…would restrict public funds for high cost procedures based on age, health, and survivability. No more Medicare open heart surgeries for 90 year olds or premium care for stage 4 cancer.”

Well that is the ultimate result of collectivism and the ACA. Joe Stalin would agree with all this.

Well actually it’s something like this:

I will pay $350k for this house, based on what other builders are/can build it for and in consideration of my 260 million friends looking for a builder also.

Does this builder want my business and my friend’s business?

Sorry, you miss the point. I was not inferring that the house could not be built for $350,000, only that you and your 260 million friends will get exactly what you pay for. The builder will build the quality that matches the payment he is getting.

Al, there is no way around this. Price controls have never ever worked in the history of civilization. Why do you insist that they can?

@ Big Al,

I agree that insurers and federal agencies hold medical prices down more than would be the case if providers could charge what they wanted. But as Frank notes, insurers and federal/state agencies are a poor substitute for the competitive behavior of consumers.

Indeed, patients have an incentive to consume care until it’s either work only their proportion of cost-sharing or until it’s too inconvenient to continue.

The fact that it is difficult for an insurer to refuse to allow a medical treatment or exclude a hospital from its network reduces insurer/federal bargaining power.

Patients controlling their own resources and being willing to walk away from a deal makes a huge difference in the behavior of providers competing for patients’ patronage.

I understand that to obtain the least expensive health care system, there would be no insurers or government, simply people shopping for medical help on their own dime. However, I’m afraid the consequences of that would be catastrophic. Would you agree?

Does the Doctor make actionable suggestions to existing laws in the article? I didn’t see any.

Good analysis. Devon.

Great piece on how markets work.

However, unless doctors, clinics and other providers are forced to list their prices, it won’t happen on a large scale. And markets can’t function properly without price information.

You have brilliantly pointed out THE fundamental problem with the healthcare system. In the current system the buyer (patient) doesn’t pay for services and the seller (physician) does not know what the price is. Your article points this out in a fantastic way for all to understand.

Think of how you select your physicians, both primary care and specialists. Where do you obtain your recommendations? What do you look for? Even if you have a high-deductible health plan, the probability is that you didn’t consider prices in your selections.

Yet another study has shown that people enrolled in consumer-directed health plans – plans designed for “price shoppers” – do not shop prices. Except for a mere 2.3% difference in prices for office visits, “prices paid by CDHP and traditional plan enrollees did not differ significantly.”

http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/fhep.ahead-of-print/fhep-2012-0028/fhep-2012-0028.xml

Think of the great multitude of articles supporting price competition in health care. All of them mention Lasik and cosmetic procedures. Do you suppose there might be something different about these procedures and the way you access them that might make them unusual outliers for which price shopping might be advantageous?

Outliers do not refute the fundamentals that Kenneth Arrow taught us about health care and markets.

It can’t because people would then be paying for all of their own healthcare.

The problem with comparing cosmetic surgery with a transparent market-based health care industry is that it illustrates how usually upper-middle to upper income people are only able to afford this service. Price transparency is a great concept but it then leads to issues of how to make prices affordable for all segments of the population.

Some non-profits have low prices for care for the low-income segment, so in this case, would be depend on these types of organizations?

Uhh… actually many middle class people get cosmetic surgery nowadays. It has become very affordable (largely because of this competition). You’ve never met a girl making 30 grand a year with a boob job? How much do you think a hooters waitress makes? Let alone the even cheaper and valuable (cheaper than contacts or glasses in the long run) lasik.

Exactly. This is pretty much the most obvious point in the world and yet politicians and the left ignore it. They decry a “failure of the market” in our healthcare system, but really, markets work great, just see plastic surgery, the problem is the rest of our system is not a market.

Also, as per the dubious “but but but in an ambulance….” claim. Cosmetic surgeons do not just do elective procedures, some things they do are reimbursed by insurance. Some people with very bad vision qualify for free lasik (I had it), some people ravaged by cancer or injury qualify for insurance covered reconstruction. The market forces that keep plastic surgery prices low for cash paying patients bleed over to these insurance covered patients as well.

If we had a true functioning market in healthcare, suppose say the cost of hospital beds were affected. Patients looking for elective procedures or no emergent care shop around for the cheapest hospital, hospitals, in an effort to reign in costs so they can compete for these patients push their suppliers, the manufacturers of hospital beds, to compete more on price too. The competition on price bleeds up the supply chain. The end result is the hospital is now getting beds for cheaper, all their beds. So when a patient having a heart attack is rushed in, they’re put a bed that cost less money, so the hospital can charge them less, even if they didn’t have the time to shop around on price.

This is one of the great things about markets. If Walgreens and Rite-Aid are across the street from each other, I do not need to visit both stores, enough customers will compare prices that I know they will be competitive with each other even if I don’t personally spend the time doing so. You don’t always have to be the one shopping around on price to reap the benefits of price competition.

As an anesthesiologist, I have conducted anesthetics for hundreds of purely cosmetic procedures. With apologies to Dr. McCanne for my lack of hard research to document my observations, about 10% of our procedures (costing $6000-$10000) were women who were on medicaid, but somehow could come up with a large cash payment.

In the pain management part of my practice, I frequently talk about cost and it is only appreciated by people who pay their own bills. As an example, people with insurance do not care if I use Lyrica or Pamelor for neuropathic pain, despite similar long-term efficacy; Lyrica being far more expensive.

My experience is that we could save a great deal of money, with no decrease in treatment efficacy if people were exposed to prices.

John, self-pay is certainly a factor in consumer behaviour, as you mentioned. What you did not acknowledge, however, is the fact that most, if not all, cosmeticic surgery is purely elective.

At least in the short run, most medical care is elective.

There is a wide gulf in health care between ambulatory procedures (literally, you walk away when it is done), vs. what I will call acute care (you stay one or more nights and you are attended by nurses).

I back up everything Devon says about how competition can drive down the price of ambulatory procedures.

However, as a former insurance company employee, I would estimate that between one half and two thirds of the cost of every policy derives from acute care.

Up to half the hospital admissions start in the emergency room.

Acute care is expensive everywhere in America. Even the nursing homes that pay very low wages still cost a lot of money every month.

Now we can get cheaper acute care by going to low wage nations like India.

That is how Walmart and GE drive down costs, so I guess we have to try it.

I don’t doubt that the majority of dollars are spent on acute care Bob. Don’t you think that a major part of the problem is that we treat all healthcare the same way in terms of management and insurance?

Realistically hospital acute care is no more related to routine healthcare than an oil change on one’s care is to an engine overhaul. Yet we have been tossing everything into the same management and insurance formulae for decades, and the ACA doubles down on all this mismanagement.

Bob, I am not clear about what you just said. There is plenty of care “(you stay one or more nights and you are attended by nurses)” that I would not define as “acute care”. It is elective, think hip or joint surgery, cataract surgery etc. Does that change the amount of money spent on non-elective acute care (think heart attack)? I think the vast amount of care leaves plenty of time for financial decisions to be considered.

Up to half the hospital admissions start in the emergency room.

I just checked out a RAND report (RR-280-ACEP) on emergency care. RAND discussed the increasing proportion of hospital admissions that originate in the Emergency Room in a diplomatic way. But I inferred from their discussion that many ER admissions are because patients’ primary care doctor doesn’t want to go through the hassle (or make their patient go through the hassle) of the formal hospital admitting process. You have to wonder about the admission process when it’s easier to wait in the ER than walk through the front door.

Having some trouble with these analogies. I don’t have to have cosmetic surgery and I don’t have to buy a certain kind of house in a specific neighborhood. But let’s say I am the parent of a four year old child with a bad rash, or vomiting, or exhibiting signs of distrees on a Saturday night – frankly I am not able to go “shopping” – especially in a less populated area – for the medical services I need. While an ambulance is not needed – the situation is not one where most would feel they have any normal consumer leverage with a provider. The other situations is what starts out as a normal childbirth runs into complications and the mother and/or newborn require more intensive postnatal care. An extra three days in intensive care will add thousands, if not tens of thousands, to the cost and the bill – and it does not involve ER – but it is virtually impossible to be a consumer on a ‘level playing field’ in this circumstances. While I am understanding of the prevailing competing philosophies regarding health care – in reality there are thousands of situations arising every single day that do not easily fit the concept of consumer choice in a competitive marketplace – regardless of whether there is third party coverage in whole or part.

Of course Patrick, the scenario you describe would fall into the category of “acute care”. That’s why you buy insurance. As you say there surely are thousands of these type scenarios every day, and there are tens of thousands of scenarios every day that do not involve acute care. Where is the analogy problem?

Patrick, as far as the 4 year old goes, wouldn’t you have gone shopping for a physician earlier like before the child was born and and already had one? By the way a lot of cash pay clinics already exist that can handle such a problem at what I would consider a reasonable cost. The complicated, expensive and unexpected normal childbirth, as Frank says, is what you need insurance for. I too am not sure what the problem is that you having with the stated analogies.

The problem is that even if I have a primary physician – he or she may not be available at the time services are needed…

And even if I have selected a provider, I have no idea what services I may be consuming in the maternity/surgery situation beforehand – so there is no true ability to “shop” or “negotiate”

If you deal with people living in more rural areas – you will find that the ‘cash pay’ clinics or urgent care clinics or even ‘community clinics’ just do not exist within any kind of proximity to residents

So all I am suggesting is that there are many situations that do not set up well for a ‘market’ – but I also criticize the ACA for including many situations that may work in urban areas but just do not work well at all outside of urban areas – neither market based nor public care seem to work well in these environments

That is the point Patrick. Healthcare does not lend itself to a “one size fits all” solution. Centralized top down healthcare systems do not work. People have different needs depending upon their location, health, physician access, personal finance, etc. The best solutions are developed by the market meeting needs rather than bureaucrats dictating policy.

…I am the parent of a four year old child with a bad rash, or vomiting, or exhibiting signs of distress on a Saturday night – frankly I am not able to go “shopping”…

@ Patrick

In a competitive market you wouldn’t have to shop in times of sudden distress. For instance, the prices in a 7-11 convenience store are generally less than double the cost at a large retailer.

It’s only in dysfunctional, uncompetitive markets (like we have in health care) that you need to worry about whether you have insurance and whether the hospital is in your network before entering the ER.

Anyone who thinks cosmetic surgery and Lasik are the same as real medical care should not be writing on health care policy.

Steve

Why isn’t cosmetic surgery a good example of real medical care? It’s performed my doctors with a similar level of training. Indeed, many cosmetic surgeons also perform other acute medical procedures where they don’t compete on price.

It seems that most of us agree that true health insurance is needed for acute care, however we describe it.

In the absence of regulations, people who are older and sicker will be charged up to six times more for true insurance than people who are younger and healthier.

($1200 a month versus $200 a month). I have sold individual insurance and this is what has happened in free-market states.

The consequence is that people who had to pay such high rates for insurance had no money left over to shop for ambulatory care.

A very few conservatives proposed some kind of subsidies for those who faced very high insurance premiums. But many conservative publications spent all their time talking about cheap interstate insurance for 40 year old males, and ignored the problem. The ACA has its own very clumsy attempt at a solution.

Although physicians do control much of how health care expenses are generated, except for most of the elective medical procedures discussed above, the vast majority of non-elective costs are reimbursed by third party payers. The only real control exerted by the patients are the costs of first dollar coverage—- when to seek care— and the choice of the provider which is usually limited by the third party plan. The fees reimbursed by third party payers are also mostly set by federal dictates. So the ideal market place, where non-elective diagnostics and therapeutics can compete by price, will only occur if the feds release their death grip on heath care reimbursements. And if one looks at the ACA, the current administration never intends to let that happen.