Understanding Why Employer Benefit Costs Are Rising Slowly

Aon Hewitt, a leading actuarial consulting firm, has reported extremely good news about the cost of employee benefits:

2015 Records Lowest U.S. Health Care Cost Increases in Nearly 20 years

– Rate of increase was 3.2%

– Average health care cost per employee topped $11,000

– Employees’ share of health care costs have increased more than 134% since 2005

After plan design changes and vendor negotiations, a recent analysis by Aon (NYSE: AON) shows the average health care rate increase for mid-size and large companies was 3.2 percent in 2015, marking the lowest rate increase since Aon began tracking the data in 1996. Aon projects average premium increases will jump to 4.1 percent in 2016.

Aon Hewitt’s 3.2 percent rate of growth includes only premium. When employees’ out-of-pocket costs are included, the reason for the slow growth becomes apparent.

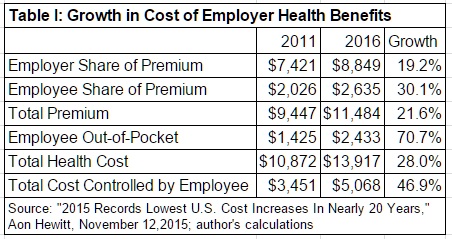

Table I shows total premium grew 21.6 percent over the six years, 2011 through 2016. However, the employee’s share of premium grew by 30.1 percent, versus just 19.2 percent for the employer. (Economically, both contributions are from the employee. The employer’s share is lost wages to the employee. Nevertheless, the employee’s share is transparent to him, whereas the employer’s share is disguised.)

Even more substantial is the growth in out-of-pocket costs: 70.7 percent over the period! This resulted in out-of-pocket costs growing from 13.1 percent to 17 percent of total health costs. That is still small, but moving in the right direction.

Americans should not bemoan the growth in out-of-pocket costs. It simply means we have more direct control of a greater share of our health dollars. It is the most obvious factor explaining relatively restrained growth in benefit costs in recent years.

Interesting material, but a couple of phrases bring out two of my longstanding complaints about the economic analysis of employer health insurance.

1. In table 1, near the bottom, the phrase “Total Cost controlled by the employee” is what Woody Allen used to call ‘jejune.’ Many workers would use a phrase more like ‘Total cost inflicted on the employee.’

2. I have long questioned the commonly used phrase “The employer’s share is lost wages to the employee.” If a state government bureaucrat has cash wages of $70,000 and a $30,000 health plan, it strains common sense to say that the $30,000 health plan is any kind of loss to him other than in a pure accounting sense. The $30,000 is a bonus on top of wages. He would not be making $100,000 a year if the employer stopped providing health insurance.

WRT to #2 Bob, I too gave thought to that one. Referring to John’s statement, one could argue that although to his point it is principally the employee who contributes (company y wants to spend x dollars on labor), the employer offers non-cash contributions such as discounts on premiums/admin fees through broker/carrier relations in addition to passing along the fundamental externalities of scale.

“He would not be making $100,000 a year if the employer stopped providing health insurance.

Well, of course not.

If the employer cancelled group medical insurance, it would free up much less than $30,000, because the employees are already paying some significant share of it. Whatever amount is freed up would be a savings to the employer’s compensation costs. The employer would then have the choice to convert all of that savings, or some part of it, into wages.

Even assuming the employer converts all of it to employee wages, the employees would not like it one bit. That’s because the additional wages would be taxable income, while the employer’s contribution toward the cost of group insurance is non-taxable compensation.

Therefore any additional wages employees could expect to receive would not be enough to allow them to purchase equivalent insurance on their own. They would be short by at least the taxes they would have to pay on the additional wages; and short by even more if the employer decided to pocket some of the savings rather than convert into wages.

If the employer dropped health coverage, the employee would need around $125K a year to make up the loss. $25K of the $55K raise would go toward additional income and payroll taxes, with the remaining $30K available to spend health insurance premiums.

Of course this ignores state income taxes.

Jimbo, feel free to point out that non-breeders would likely need less than the hypothetical $30K.

Well, if he were sent to the private sector, he would not get paid that much. However, unless there was a secular or cyclical drop in the cost of labor, he would demand at least $100,000 in cash wages. He would demand more, because if he remained an employee he would have to use after-tax dollars to pay premium, for individual health insurance. (He might get Obamacare tax credits.) Or are you suggesting he would just accept a 30-percent pay cut and not get a job elsewhere as soon as possible?

I agree with Bob about the “total cost being controlled by the employee.” Only someone who is deluded with themselves would make such a comment as the out of pocket maximums plus the premiums paid are not controlled by the consumer. I have been an independent agent for thirty years and the ACA is another acronym for cost-shifting and not consumerism.

Are these costs averaged out for employees and dependents or for employees only

According to Kaiser Family Foundation average family premiums are about $17,500 per year

Don Levit

Aon Hewitt refers to employees. Employees usually pay all (or almost all) dependent coverage these days.

Let me elaborate on why I believe that health insurance is more like a bonus from the employer, vs. lost wages to the employee.

Let us say that the going wage for an auto mechanic in Minneapolis is $40,000 a year across a wide spectrum of firms.

A mechanic in a small family owned garage may not receive any health insurance from his employer. But a mechanic who works for the State of MN in their motor pool receives a $40,000 salary plus a health insurance plan worth $15,000 to him and his family.

The owner of the small garage does not have to offer a $55,000 salary to get a qualified worker. The labor market sets this job at $40,000.

The state is just paying a bonus on a $40,000 job.

Thank you but that is not fair labor competition. There are a limited number of public-sector jobs that pay more than their private sector equivalents. If you don’t get one of those jobs, you get less.