Obama Administration Health Care Rule Making Is a Disordered Mess

In a series of papers for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Christopher Conover and Jerry Ellig provide evidence to suggest that “the involvement of both White House and high-ranking agency staff” suggests that “the administration likely got the [ObamaCare] rules it wanted written.” To do this, it overrode the normal checks and balances used to ensure that federal regulations impose the smallest possible burden on the private sector. Rather than posting required regulatory impact analyses (RIAs) with interim rules and allowing time for analysis and comment, the White House and its agency heads dictated the rules that would be written, curbed the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) review function, and then simply declared that the interim rules were final.

In 2008, the average regulation received 56 days of OMB review. In 2009, the average regulation received 27 days of review. In 2010, the average ObamaCare regulation received 5 days of review. The RIAs accompanying the regulations were “seriously incomplete, and they fell far short of federal agencies’ normal practice.” The economic impact of the resulting regulations was so poorly understood that the authors suggest that Congress should consider establishing a review agency that is independent of politics and can “review agency regulatory analysis according to widely accepted standards.”

Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off

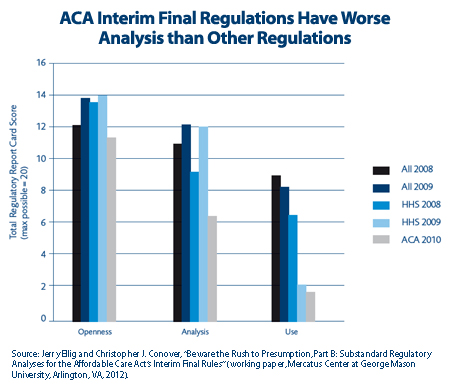

As the chart below shows, poor analysis produced poor quality regulations.

Executive Order 12866 states that RIAs should “assess the systemic problem a regulation is supposed to solve, define the outcomes the regulation is supposed to produce for the public, examine a wide variety of alternative solutions, and assess the pros and cons (benefits and costs) of the alternatives.” An RIA is then supposed to be made available for public comment before a final rule is passed. The agency must consider public comment in formulating the final rule.

Executive Order 12866 states that RIAs should “assess the systemic problem a regulation is supposed to solve, define the outcomes the regulation is supposed to produce for the public, examine a wide variety of alternative solutions, and assess the pros and cons (benefits and costs) of the alternatives.” An RIA is then supposed to be made available for public comment before a final rule is passed. The agency must consider public comment in formulating the final rule.

Rather than following the Executive Order, the “agencies decided on, wrote, and published the results without first publishing a proposal or RIA for public comment.” Specific analytical shortcomings include

- Benefits estimates that tended to be biased upwards

- Benefits estimates that were theoretically wrong, as when analysts confused transfers with efficiency benefits.

- Cost estimates that were biased downwards, usually due to a failure to consider entire categories of costs such as the efficiency losses associated with using higher taxes to finance a regulation.

- Net benefits estimates that were biased upwards, “in some cases with biases large enough to call into question whether the benefits of new rules exceed their costs.”

- Analyses that “ignored less-expensive alternatives that would be obvious to most health policy analysts.”

- Often cited benefits from increased “equity,” although the analytical effort was apparently so poor that the authors concluded that “When the word ‘equity’ appears at all, it is employed as a rhetorical embellishment rather than a serious category of analysis.”

In some cases, the regulations may impose costs that are higher than their benefits. Though the paper does not assess whether accurately calculated costs exceed accurately calculated benefits, it does find that The Early Retiree Reinsurance Program, the Pre-Existing Condition Insurance, and the Dependent Coverage for Children up to Age 26, “probably” generate more costs than benefits. Rules requiring guaranteed issue and eliminating lifetime benefit maximums “possibly” produce higher costs than benefits, as does the mandate to cover “preventive services” and the much ballyhooed, but undersubscribed, federal pre-existing condition pool. The relationship of net benefits to net costs in the rules for grandfathering health plans, the rules for claims appeals and external review processes, and the rules for calculating Medical Loss Ratios are considered “uncertain.”

The efficiency losses created by tax based finance are ignored both in the RIAs and in the public debate. They are generally understood to be large and significant costs. Since 1992, the Office of Management and Budget has required federal agencies to assign a shadow cost for the lost production of 25 cents to every $1 of expenditures. The authors note that other analyses suggest that the “deadweight loss” from taxation, the losses that occur because taxes distort the signals sent by the price system, for each dollar collected are as high as 44 cents. For the Early Retiree Reinsurance program, ignoring deadweight losses understates costs by roughly 44 percent of the program’s estimated costs of $2.2 billion.

The losses from the increased moral hazard generated by ObamaCare’s Medical Loss Ratio regulations were also systematically ignored. The amounts in question are substantial. As the authors point out, health insurance fraud alone accounts for an estimated 3 to 10 percent of annual US health care spending. Only 10 percent of the estimated fraud is actually discovered and only 10 percent of those funds are actually recovered. In view of this poor success rate, general opinion seems to hold that the biggest cost saving from anti-fraud measures comes from preventing fraud in the first place.

The authors note that the current health system “massively underinvests in fraud prevention/detection.” In view of this, the officials writing ObamaCare’s Medical Loss Ratio regulations could have decided to exempt all spending on anti-fraud activities from the Medical Loss Ratio calculation. Instead, they wrote rules that penalize insurers who spent more on deterring fraud. For example, a health plan spending $15 in administration for every $100 in premiums would be in violation of the Medical Loss Ratio regulations if it spent another $1 to prevent $5 in fraudulent claims. Spending the extra $1 would cause its Medical Loss Ratio would drop to 83 percent ($16/$100) because the $5 in fraudulent claims would never be paid, and would therefore never be entered into the denominator of the calculation.

Though insensitive to fraud prevention, the RIA analysis of Medical Loss Ratios was exquisitely sensitive to convenient definitions of equity. For example, readers are informed that the rebates required under the regulation would lead to “less disparate MLRs and value to consumers across issuers and States.”

This, as the authors point out, is nonsense. “Why equal percentages of expenditures are equitable is not explained. Indeed, if we assume the real goal is to equalize health outcomes across states, the equity claim is questionable, because differences in costs, insured populations, or market characteristics across states might require unequal MLRs to achieve the same outcomes for patients; equal MLRs could exacerbate inequality of outcomes.”

The inequity generated by the subsidized rates for people in the federal pre-existing conditions program, was ignored. Because people have to be uninsured for 6 months before enrolling, individuals in states with high-risk pools are required to either stay in those pools and pay higher premiums or go without insurance for six months to qualify for the federal program. This, as the authors point out, “arguably penalizes consumers who are currently in state high-risk pools, which appears to be a source of inequity worth commenting on.”

Parts of the rules simply seem irrational. The rules on Grandfathered Health Plans entirely prohibit changes in coinsurance while allowing copays to rise by inflation plus 15 percent. What, the authors ask, “is the rationale for limiting coinsurance changes to medical inflation plus 0 percent?” They conclude that there is no logical justification for tilting the playing field in “favor of plans that have adopted a copayment structure. Regulators apparently did not even consider an alternative that would have treated such plans similarly” even though they could have adopted a less restrictive actuarial equivalence standard.

Why didn’t the government adopt the actuarial equivalence standard? The RIA analysts said that using actuarial equivalence was just too complex and costly. This excuse does not hold water. As the authors point out, actuarial equivalence is used in Medicare Part D. It has been used to evaluate Massachusetts Connector Authority Plan benefit structure since 2006. Even more embarrassing, ObamaCare actually requires its use in structuring plans offered in the health insurance exchanges.

A problem with ill-conceived laws is the need for regulations to mitigate some of the market-distorting effects. When the regulations result in additional market-distorting effects, more regulations are needed.

As we’ve said many times in the past; whether you are a supporter or an opponent of the Affordable Care Act, the law will have to be revisited to correct some of the structural flaws.

Great post, Linda.

Regulators to regulate the regulators. Sounds like bureaucracy heaven– all with paychecks and generous government benefits. Pretty soon we will have full employment.

I think I see a pattern here. Let’s call the whole thing off!!

Love watching Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Egads. Almost speechless.

The Law of Unintended Consequences happens when people just want control, just want to continue their membership in the worlds greatest country club – Congress. They wrote a law regulating an industry they just don’t understand, and we have to live with the Unintended Consequences – like mandating children only coverage, no health questions, no pre-x exclusions – so what happens – all the carriers stop issuing children coverage. Now even the healthy can’t buy coverage. This law has ‘idiot’ author written all over it.

Agree: Let’s call the whole thing off.

Hopefully SCOTUS will do it for us – teach them a lesson – do what is right and will work, not what is you their own self interest.

For those of us out in the field–in the real world–trying to cope with the onslaught of “make-it-up-as-you-go-along” reform, your post quantifies what we are trying to deal with daily. My law firm, Physicians’ Advocates, represents doctors and their organizations nationwide. The pace of new regulations affecting the practice of medicine is not the only dizzying in its rapidity, but the content of the regs is also dizzying. The bureaucratic disconnect between how Americans really get their health care everyday and the dystopian vision that is being rushed into place by regulatory fiat is virtually impossible to navigate.

For the lawyers in my firm, it is our job to try to figure out what these regulations really mean for the daily delivery of medical care, and to advise our clients on the most prudent course of action. When regulations are spit out at such a furious speed with little or no input from those affected(contrary to the intent of the Administrative Practices Act), the only law that is sure to apply is The Law of Unintended Consequences.

Nothing is more costly to an economic system than uncertainty. When one fifth of our economy is being turned on its ear by unchecked bureaucracy to the point that the players in the economic system do not know which way to turn, it is unrealistic to think that any of the players will take risks to innovate or do anything other than charge the highest possible price to hedge against the uncertainties of tommorrow.

I am sure that those promulgating the regulations have the very best intentions, (and the regulatory swarm is undoubtedly a stop-gap strategy in case the Supreme Court invalidates all or part of the health reform legislation), but the practical effect of any new regulation is to raise costs by at least the amount necessary to comply.

Two weeks ago I gave a talk at the California Society of Health Care Attorneys, and noted, for example, that the cost of implementing the ACO strategy envisioned by the Administration (and embraced by Republicans as well) would require the greatest expenditures in health care history in America, and would constitute the most costly social reorganization since the Industrial Revolution. This reorganization of the health care delivery system–however much it may be needed–is being imposed just when America is facing the largest demographic bulge in history. Thus, the next generations will be asked to pay the tab–not only for the cost of caring for the aging Baby Boomers–but for the capital costs of integrating and modernizing a cottage industry that constitutes one fifth of the American GDP and equals the GDP of China.

One of the great problems is that governmental health policy, as embraced by politicians and bureaucrats,since the time of Herbert Hoover, has been pushing the providers into aggregated care, not truly integrated care. Thus, mass matters more than the acchievement of true efficiencies. We simply cannot afford to both provide the care needed to our aging population and capitalize the streamlining of our system into a sleek Ferrari-like machine.

Our steps need to be much less ambitious, and much more American. They must be rooted in both our belief in individual rights and responsibilities and in our traditions of community spirit. All health care is individual, so each of us needs to do what we can. (See e.g., the new IOM report on obesity.) We need to promote individual responsibility for health, then recognize that we do not have the resources nationally to continue to provide complex institutional solutions for every health problem. As a society, practically speaking, we do take care of everyone. That is our ethic, and so the debate about “universal access to care” needs to move to “how” not “whether.” We are not a nation of “Let ’em lie in the street and bleed.” Every poll and opinion sample reaffirms that we are a people who, regardless of religious persuasion, believe in the teaching of the principles of the parable of the Good Samaritan. Right now, however, we are “passing on the other side.” Our reliance on big health plans, big hospitals and big government has de-personalized health care, so that the social presumption is that health care should be delivered by a stranger. That is not the way it is in real life and that is certainly not the way it works in the rest of the world. Families need to learn how to care for one another and be supported in providing that care. (See numerous studies showing cheaper, better outcomes for treatment at home rather than in the hospital.) Neighbors need to care for neighbors. (See public studies repeatedly showing that not only do patients fare better if they have a “care-buddy”, but the care-buddy shows better health indicators too.) In short, we need to learn how to take care of one another.

That is the true health care reform we need. It is how we can reform health care from the grass roots up, not from the top down. It is how we can trim the cost of care that is threatening to bankrupt millions and millions of Americans and the country itself. It starts with us–not with the President, the Congress, or the army of medicrats. Building this awareness is the mission of the movement known as the Patient-Physician Alliance, and that is what I am devoting my time and energy too. I would warmly welcome the company of the many very smart and savvy readers of this blog.

Cordially,

Charlie Bond

The aspiring communist dictator strikes again.

BO Something Stinks in DC!

Re: ‘Parts of the rules simply seem irrational. The rules on Grandfathered Health Plans entirely prohibit changes in coinsurance while allowing copays to rise by inflation plus 15 percent. What, the authors ask, “is the rationale for limiting coinsurance changes to medical inflation plus 0 percent?”’

Coinsurance is a percent of service cost (20% of $500, for example), so the patient share automatically increases with higher costs year-to-year even if the coinsurance rate (20%) does not. Copays are fixed dollar amounts, so to just ‘keep up’ with medical inflation the explicit adjustment is required.

Nonsensical? Only if you are uninformed.

WE have to pass the bill to see what is wrong with it!