Is Consumer-Driven Health Care Hurting Hospitals? (And Should We Care?)

Dobson DaVanzo, a leading consulting firm, has produced a report for the Federation of American Hospitals, the trade association for for-profit hospitals. The report notes that the rate of change of health spending has slowed down. Indeed, the report concludes that spending is set to shrink this year by over one percent. This introduces a “paradox”:

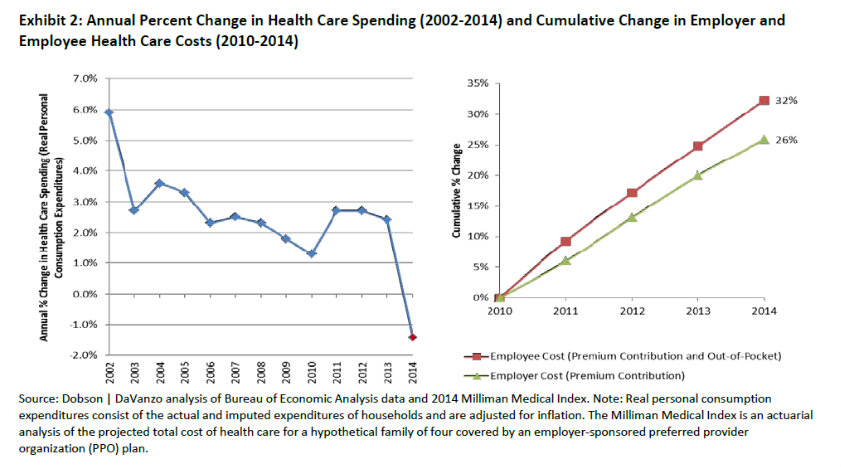

However, paradoxically, consumers perceive that their health care spending is increasing more than usual. This perception is largely a result of spending on their health care increasing faster than personal income combined with a continuing redesign of their health insurance benefits, which shifts more of the cost burden onto consumers:

- Almost 60% of Americans think that health care costs have been growing faster than usual in recent years, and more than 70% of consumers attribute responsibility for their perceived high and rising costs to health insurance companies.

- Total premiums have increased substantially over the past decade, from 14.9% to 21.6% of median household income between 2003 and 2012.

- Employee contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket spending have risen 23% faster than employee costs since 2009 (32% in cumulative growth vs. 26%) (See Exhibit 2).

We think this “paradox” is explained by consumers gradually becoming free of the money illusion that someone else (usually, the employer) is paying for their health care. This is a desired result of consumer-driven health care. One of the problems for hospitals is that consumers with high-deductible health plans get admitted and are unwilling to pay their out-of-pocket share of the hospital charges. One Congressman told me that one third of the uncompensated care provided by the largest hospital in his district was accounted for by insured patients.

This is a problem for hospitals, but should we care? No and yes. To the degree hospitals’ financial problems are caused by their buying up physicians’ practices so that they can charge higher fees for the same services, we should ignore their pleas. However, many inpatient procedures are truly catastrophic situations, rare and insured. In these cases, patients should not be faced with deductibles that are high for them but a small share of the charge. This requires significant reforms to the design of health insurance that are not possible under traditional health insurance, which levies co-pays and deductibles based on twelve-month enrollment periods instead of incidents of disease or accidents. Hospitals (and pharmaceutical companies and medical-device makers, too) should get onboard the movement to re-design health insurance along these lines.

(Recall that although hospital inpatient costs are the single largest factor in reducing the rate of Medicare spending growth, Obamacare has led to increased hospital admissions and profits.)

I think consumers being in control of their health spending is a good thing, and if hospitals are only hurting because of this:

“hospitals’ financial problems are caused by their buying up physicians’ practices so that they can charge higher fees for the same services,”

then this should clean up any inflating pricing done by hospitals. Consumer driven health plans are going to lead to more price transparency.

If hospitals didn’t want kick back from prices, then they shouldn’t be buying practices so they can charge higher prices.

Efficient prices are about competition people!

The way hospitals are loving an increase in Medicaid patients and are receiving higher profits from Obamacare, no wonder they are kicking back when consumers are in control of their health plans.

I think significant reforms are needed to combat this, in the best interest for patients and hospitals.

This is why value-based health plan design and reference pricing is important. Hospitals are great when you need them. But they are very expensive places to receive ambulatory care. There is nothing inherently different about hospitals that makes this so. It’s (arguably) a function of the fact that patients only pay 3% of their hospital bills out of pocket. When 97% of hospital bills are paid for by 3rd parties, hospitals don’t have to compete on price. Rather, they compete in other ways.

“When 97% of hospital bills are paid for by 3rd parties, hospitals don’t have to compete on price. Rather, they compete in other ways. ‘

Well said, Devon, and this does not translate to lower costs for patients.

Very interesting

Let me add to what Devon is saying.

Not long ago I had some outpatient care done at an office which had been purchased by a hospital.

The price to me had doubled.

But I was not in a hospital. I did not know I was dealing with a hsopital entity. The whole episode was about as transparent as a brick wall.

The Center for Public Integrity has some good pieces on this injustice.

Yes Bob, and the hospitals are touting these moves as “better for patient care”. Better for their bottom line is more like it.

CDHPs may indeed lower costs, but what are the effects of premiums?

If lower costs still lead to premium increases higher than income, then the battle is lost.

With premiums over 20% of median household income, it looks like we are losing the battle in controlling costs that result in real premium reductions.

Don Levit

Thank you. That is a very good point. Simply shifting cost from insurers to patients does not do much for consumer-directed health care.

Price formation, signalling, and innovation in service deliver that come from responding to patients’ needs are much more important. And this requires the whole notion of networks to be re-thought.

For years we have been told that insurance premiums were going up because of ‘overall medical inflation.’ Insurance companies actually used terms like ‘medical trends’ to justify part of their regular 10% increases.

But as pointed out in this post, we now see the medical trend going flat, but insurance premiums keep going up. What gives?

Numerous causes, but here are two to think about:

a. stagnant risk pools

The people actually covered in an employer plan may be just getting older. I believe that health costs go up 6% with each birthday.

b. flat investment earnings

Insurance companies have to invest safely and with high liquidity. i.e. the insurers are lucky to earn 2% on their cash flow.

(this is part of what drives long term care premiums up also)

Thank you for those very good comments. What you’ve written about the aging of the employer-based insured is the mirror-image of what we see in Medicare: The baby-boomers are reducing the age of the Medicare risk-pool and increasing the age of the employer-based one.

Bob:

Excellent points

Investment income used to be an important part of an insurer’s profit

Now that interest rates have plunged and insurers are limited in the stock market risk they can take

we have to go back to the fundamentals of pooling

While pools may be aging the percentage of people having high medical claims has stayed the same

As long as 10-20 percent of the pool incur 80 percent of the claims we can reward the 80-90 percent who have lower claims

Every premium dollar not used as claims is available for reserves

And it is the reserves that can be shared with those low claimants in the form of paid for benefits

Once reserves are lowered due to low claimants’ higher claims so too are their paid for benefits

The average insured will build more in paid for benefits than claims, thus increasing our reserves and increasing his paid for benefits

It is this type of long term partnership which we believe will allow National Prosperity Life and Health to flourish along with our insured partners

Don Levit,CLU,ChFC

Treasurer of NPLH

Dear John and Constant Readers:

Most of your comments were on pricing and insurance, plus consumer psychology. There is an implied belief that hospitals should price according to consumer expectations of value. It’s wrong for an MRI to cost 5 times as much in one hospital as another, for example. Transparency is a virtue. Okay so far.

But there is an implied belief that hospital prices can be modified in the short term by competition; that hospitals are just greedy if they continue to price so it gives us gas pains.

But hospitals are like giant elephants–they can’t make themselves into gazelles at will, or ever. They are the most costly buildings known to man short of a particle beam accelerator. They build in capacity for outpatient services so they can spread their fixed costs over more people. State regulators make them build that outpatient capacity to hospital specifications. So–$1,000 per square foot. As medical care naturally is migrating to outpatient settings, hospitals are now building new buildings like regular doctors’ offices. But if they include surgeries, the cost is about the same.

Most hospitals borrow the capital to build, which means they have to pay it back, making the total money about twice the direct construction cost. As hospital loans are for 30 years, the hospital can’t slash prices in the short term and still make debt service. Communities used to do fund-raising for their new hospitals–now they cost too much to do that. Look at UCSF–$2 + billion and counting, with gifts at about 25% of that.

Another underlying assumption is that costs vary directly with the number of patients and their acuity, or level of illness, so that if you refuse readmissions, somehow those costs go away. No they don’t; they are loaded onto the patients that remain. There are still elevators to fix, lights to go on, computers to buy, unions to pay, and surgical instruments that wear out. Only food and some staff plus a few drugs do vary by patient. So forget trying to influence hospital COSTS by the method of payment. As health plans pay less, three things happen, not all salutary: hospitals lay off staff, they create waiting lists for services so they only have to have part of a service open at a time, and they CLOSE–either a single service, a whole program or a total hospital. On the way, they use up reserves, then stop paying their debt service. Nobody in the hospital works for free, especially not unionized workers. People outside of hospitals are not aware that hospitals are the single most regulated business in our economy.

If health plans paid doctors more, they would take care of more patients in their offices, but they won’t compete with the ER on pricing for primary care because, even though it costs less to see a patient in an office, government patients still will not pay enough to keep the office open in competition with the ER.

It’s no good talking about global pricing, as it protects the health plan from knowing what his money is buying. FFS is difficult, but it does produce useful data. Global pricing is likely to cover services according to the political power of the various specialties. Good pay for surgery, lousy for OB.

It ain’t easy being a hospital administrator. But they do hide a lot and have done a totally nothing job of educating the public about hospital charges.

Luv to all,

Wanda Jones

San Francisco.

Thank you. We appreciate your expertise at the blog.

Unfortunately, we do not think it is always a back thing for hospitals to lay off workers or even go bankrupt. If the ASCs, for example, can do the job at lower cost, and the hospitals cannot cover their debt-servicing costs, that is the way the cookie crumbles.

One of the major problems with the non-profit community hospitals is that, because they cannot pay dividends to shareholders, the economic profits get turned into excess capital expenditure and other costs.