Government Health Spending Growth Outstrips Private Sector Growth in Both the UK and the US

Here are some data suggesting that health spending increases are, as theory suggests, difficult for the public sector to control. If true, a long run strategy that seeks to control expenditures by increasing the fraction of health spending under government control is more likely to increase expenditures than reduce them.

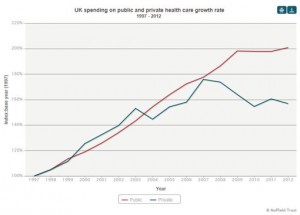

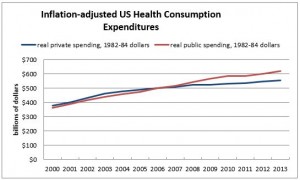

The two charts below show different measures of inflation-adjusted spending by the public and private sectors in the United Kingdom and the United States.

The first chart is from the Nuffield Trust for Research and Studies in Health Services, a British foundation devoted to “evidence-based research and policy analysis for improving health care in the UK.” It shows that inflation-adjusted UK public spending on health has increased by more than 200 percent since 1997. Inflation-adjusted public spending increased by 68 percent between 2000 and 2012. Private spending increased by 26 percent. Over the same time period, the population of the United Kingdom rose from about 59 million to 64 million, an increase of almost 7 percent.

The next chart shows the growth in US public and private health consumption expenditures. US public spending rose more slowly than in the UK but more rapidly than in the US private sector. From 2000 to 2012, inflation-adjusted spending rose 67 percent in the public sector and 44.5 percent in the private sector. Expenditure growth was slower even though the US population grew by 27.3 million people or 9.7 percent, a larger percentage growth rate than in the UK.

In the US, private spending on health consumption includes out-of-pocket spending and spending on private health insurance. Public spending on health consumption includes federal, state, and local spending on Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, the Department of Defense health program, school health programs, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, workers’ compensation, and other programs. Consumption expenditures do not include investment. Data are from the National Health Expenditure Accounts. The 1982-84 Consumer Price Index was used for the inflation adjustment.

Interesting data. Thanks, Linda Gorman. And, while this isn’t your fault, the Nuffield people mislabeled their graph in two ways. First, the heading should not include the term “growth rate” because the graph doesn’t show the growth rate directly: it shows the absolute level. Second, the vertical axis on the graph should not have the term %. It’s an index.

You are saying that indexes don’t go up or down. I think they do, so I see the idea behind the graph.

I do agree that percentage increases and decreases ought not be the sole consideration. That can lead to misleading information, if one is unskilled in interpreting such stuff.

I’m not sure what to conclude from these data. While population increase is mentioned, is that the correct adjustment? Would it not be the population covered in each category; i.e., numbers covered by public and private programs? If so, does it change the rates of increase?

For me a more helpful statistic would be inflation adjusted increase per capita (and how are dependents counted?) in each category.

I completely agree about standardizing the population and so on. It would be nice to be able to statistically correct for everything. And thanks to David Henderson for catching the labeling.

Unfortunately, standardizing data between two different countries is not a simple thing to do. Which is why I stuck with expenditure growth rates.

The point of this post is that we are continually told that US health spending increases will moderate if we move from a decentralized (“fragmented”) system to a centrally controlled (“integrated” “clinical pathways” “best practices” “pay for performance” system). As a general matter, these assertions are supported by surprisingly limited evidence.

Economic theory suggests that top down management is unlikely to perform well in an organization sized to serve the populations as big as those in the US or UK.

Theory aside, what happens in practice? It seems to me that if those assertions are in fact a solution, then we should be able to see much smaller spending growth in countries that have already instituted them and, like Britain, have in fact had them in place for decades.

As a first approximation, the rough expenditure increase data presented here do not support the contention that shifting to a centrally controlled system automatically moderates spending growth.

Last time I looked, just over 10 percent of British citizens had private health insurance. There is a self-pay system operating in parallel with the NHS. A 2011 Telegraph article said that it is used by an estimated 250,000 people a year to avoid NHS waiting lists. [http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/personalfinance/insurance/privatemedical/8438496/Whats-the-cost-of-beating-NHS-waiting-lists.html]

Population increase? It caught my attention, but totally different from your take. The USA has an illegal immigration problem. People no longer come here for Americanization, they come here for benefits. Statistically, even those who do some work, the benefits provided by the government outstrip their contribution to the tax rolls.

Then, look at the, if you will, “organic” growth in population whether it be with US citizens or illegals, we are producing a nation of dependents.

It’s mostly outflow, which fiscally is destroying the USA. Your idea is fine, but way too complicated. Bill Earle said it all, “when your outgo exceeds your income, your upkeep will be your downfall.” That says it all.

The US national government has no business being in the welfare business. The Constitution doesn’t allow for it, but the politicians and bureau-rats make get their power by continuing the hoax.

I suspect the health care spending, specifically that portion paid for by the Federal Government , will continue to increase, possibly at an accelerating rate. The Federal Government can and will continue to issue more debt, scoffed up by the Federal Reserve Bank with “printed money” , in order to pay for Medicare (that portion not paid for by beneficiaries) and Medicaid and the VA and other programs.

As most of the care is provided and paid for domestically, this dynamic can go on and on unless or until such time as some entity or entities (other countries) say enough is enough.

Of course all this increased the demand for care and, in turn , drives up the cost. This puts more cost pressures on private payers – individuals and insurance companies and the like – and drives more people to government paid for care.

Where, when and how it ends is anyone’s guess.

While I agree that it is hard to control spending in a centralized bureaucracy, there is another explanation (at least for the US) for why government spending increased faster than private spending. The US government covers a different population than the private sector. Poor people and old people may see higher spending growth. The switch in what sector spent more came around 2007 or 2008. At that point, we see more baby-boomers going on Medcare and more people becoming eligible for Medicaid (due to the recession). This appears to be less of “bureaucracies cannot control costs”, which would suggest a difference in per capita spending (adjusted for health status), than just more people are on government health roles.

Plus Medicare Part D drug benefit kicked in during the period. But I am not sure that is the point. The have been no similar additions to the British NHS during the period, and yet public spending increased.