Do We Really Spend More and Get Less?

The conventional wisdom in health policy is that the United States spends far more than any other country and enjoys mediocre health outcomes. This judgment is repeated so often and so forcefully that you will almost never see it questioned. And yet it may not be true.

Indeed, the reverse may be true. We may be spending less and getting more.

The case for the critics was bolstered last week by a new OECD report that concluded:

The United States spends two-and-a-half times more than the OECD average health expenditure per person … It even spends twice as much as France, for example, a country which is generally accepted as having very good health services. At 17.4% of GDP in 2009, U.S. health spending is half as much again as any other country, and nearly twice the average.

Similar claims were made recently in The New York Times by former White House health advisor, Zeke Emanuel, who added that we are not getting better health care as a result. The same charge was aired at the Health Affairs blog the other day by Obama Social Security Advisory Board appointee Henry Aaron and health economist Paul Ginsburg. It is standard fare at Ezra Klein’s blog, at The Incidental Economist and at the Commonwealth Fund. It is also unquestioned dogma for New York Times columnist, Paul Krugman.

What are all these people missing? On the spending side, they are overlooking one of the most basic concepts in all of economics.

You can’t always get what you want.

When you and I buy something, the cost to us is the price we pay for it. But that is not necessarily true for society as a whole. The social cost of something may be a whole lot more or a whole lot less than what people actually spend on it; and that is especially true in health care.

In the United States and throughout the developed world, the market for medical care has been so systematically suppressed that no one ever sees a real price for anything. Patients never see the real price of the care they receive; doctors never receive a real price for the care they deliver; employees never see a real premium for their health insurance, etc.

In the United States, for example, a typical doctor is paid one fee by Medicare, a different fee by Medicaid, and a third fee by BlueCross. Moreover, there are different fees for all the other insurers and for all the employer plans. These fees do not count as real market prices, however. Instead, they are artificial payments that often reflect the bargaining power of the various payer bureaucracies. When government accountants sum up all the spending on health care, therefore, they are adding artificial price times quantity, for all the separate transactions, to arrive at a grand spending total.

Here is the kicker: since each separate purchase involves an artificial price, no one knows what the aggregate number really means. To make matters worse, other countries are more aggressive than we are at shifting costs and hiding costs. They use their buying power to suppress the incomes of doctors, nurses and other medical personnel much more than the United States does, for example. In addition, formal accounting ignores the cost of rationing in other countries. In Greece, patients spend nearly as much on bribes and other “informal” payments as they do on “formal” costs such as insurance co-pays. Yet these bribes do not show up in the official statistics. Bottom line: in comparing international spending totals, we are usually comparing apples and oranges.

Let’s take doctor incomes and government health care programs. One way to pay doctors is to pay market prices — whatever fees are necessary in order to induce them to voluntarily provide medical services. Another way is to draft them and pay them little more than a minimum wage — as the government has done in the past in times of war. Obviously, the second method involves a lot lower spending figure. But to economists, the social cost is the same in both cases.

The reason? To economists, the social cost of having one more man or woman become a doctor is the next best use of that person’s talents. Instead of becoming a doctor, the pre-med student might have become an engineer, say, or an architect. So what society as a whole must give up in order to have one more doctor is the loss of the engineering or architectural goods and services the young man or woman would otherwise have produced. This cost, called “opportunity cost,” is independent of how much doctors actually get paid.

The principle also applies to other medical personnel and to buildings and equipment. The opportunity cost of a hospital, for example, is the value of a commercial office building or some other use to which those same resources could be put.

The concept of opportunity cost allows us to see that if we don’t trust spending totals in the international accounts, there is another way to assess the cost of health care. We can count up the real resources being used. Other things equal, a country that has more doctors per capita, more hospital beds, etc., is devoting more of its real income to health care than one that uses fewer resources — regardless of its reported spending.

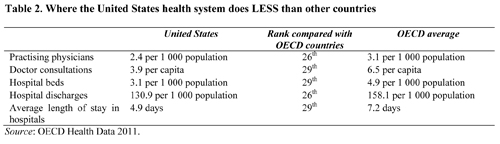

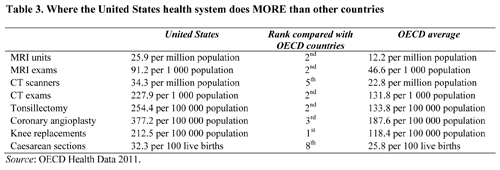

On this score, the United States looks really good. As the table below (from the latest OECD report) shows, the U.S. has fewer doctors, fewer physician visits, fewer hospital beds, fewer hospital stays and less time in the hospital than the OECD average. We’re not just a little bit lower. We are among the lowest in the developed world. In fact, about the only area where we “spend” more is on technology (MRI and CT scans, for example), as is reflected in the second table.

Almost a decade ago, Mark Pauly estimated the cost of health care across different countries based on the use of labor (doctors, nurses, etc.) alone. The finding: The U.S. spends a lot less than such northern European countries as Iceland, Sweden and Norway and even less than Germany and France!

What about outcomes? Do we get more and better care for the resources we devote? Here the evidence is mixed. As the second table shows, we replace more knees per capita than any other country and it’s hard to believe that any of these are unnecessary procedures. On the other hand, if you think that there are too many tonsillectomies and Caesarean births, our ranking there (2nd and 8th, respectively), may be less admirable. Avik Roy has a nice presentation of cancer survival rates. The U.S. basically leads the world.

What about life expectancy statistics — a favorite of the critics, since Americans don’t score very high? It turns out that when you remove outcomes doctors have almost no impact on — death from fatal injuries (car accidents, violent crime, etc.) — U.S. life expectancy jumps from 19th in the world to number one!

This isn’t to say we don’t have problems. There is a lot of evidence of waste and inefficiency in U.S. health care. Still, it’s not clear that we have any reason to feel inferior to the rest of the world.

very interesting perspective. Good Post.

Excellent post as usual. I worked in Canada for 13 years as a physician prior to coming to the US. People totally gloss over the cost associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment when accounting for health care costs of a country. If you wait a year or two to have an illness addressed, what of the lost productivity? It is not factored into costs. My brother suffered very serious morbidity from markedly delayed cancer diagnosis in Canada. I am positive, it would have been diagnosed a full year earlier in the US. The treatment required was therefore far more radical than it should have been resulting in serious morbidity. He has had to take early retirement as a result removing about ten years of productivity from his career. The loss to the economy will never be accounted for as part of health care costs.

Why be proud of being number 1 at replacing knees and having the best technology, when we rank below average at providing basic care and when it comes to practicing physicians, doctor consultations and hospital capacity?

If truth really matters…

If we took the expenditures per enrollee on Medicare and multiplied them by the US population, and divided it by the GDP, we would spend 22.52% of GDP.

If we took the expenditures per enrollee on Medicaid and multiplied them by the US population, and divided it by the GDP, we would spend 18.00% of GDP.

If we took the expenditures per enrollee on private insurance and multiplied them by the US population, and divided it by the GDP, we would spend 12.90% of GDP.

The United States spends more on health care than other countries. We are often criticized for not getting our money’s worth. The only reason this is even a topic for discussion is because taxpayers pay the tab for half of all medical care. Another 40% is paid by 3rd party insurers. If medical care were just another good or service — like transportation — people would decide on the amenities they prefer and pundits would have little cause for concern.

These are good arguments. Great post!

Hmmm…we spend more but don’t really spend more. We don’t live as long but really live longer….

Some specifics: (1) few knee replacements are unnecessary….except maybe in Fort Myers? You know that data;(2) link to Avik Roy went to article unrelated to cancer outcomes, so I can’t comment; (3) US life expectancy for age 65+ women lower than most OECD countries. I doubt that many of them die from fatal gunshots. At least, haven’t read any studies showing that.

This column is too much of a stretch to take seriously….doesn’t pass the laugh test.

I have long thought that the US has the best healthcare system in the world, and that we are destroying it through political pandering to economically ignorant voters who want more given to them. I am old enough to remember the doctor coming to my grandmother’s home, examining her and dispensing pills from his black bag. Unfortunately, health care is not the only thing we are destroying. I fear that there will be a fiscal collapse, followed by a social and political collapse. People in30 years will envy us. On the plus side, I have pulmonary fibrosis, so won’t be here for the looming disaster. I will link to this from my Old Jarhead blog.

Robert A. Hall

Author: The Coming Collapse of the American Republic

(All royalties go to a charity to help wounded veterans)

For a free PDF of my book, write tartanmarine(at)gmail.com

Why would prices deteremined as a result of a bargaining process, whereby each participant uses their individual leverage to their own advantage, result in an “artificial” price? In fact, I would agrue the exact opposite, if an individual were to ignore their bargaining power and accept any other price than that which was most favorable to them, then that price would be artificial. By this logic Bulk pricing (lower prices for by greater amounts) would be an “artificial” price. The reason large insurance companies can negotiate a price for health services is that they have a large pool of potential patients and lower reimbursement risks, therefore healthcare entities that contract with large insurers will increase the size of their market and be relatively more certain of receiving payments, albeit reduced due to the negotiated price. If we were to compare physician fee schedules between countries instead, this analysis would be wholly unrelated to market prices at all due mainly to the interference of third party payer contracts. The comparison should be made on actual expenditures, including implicit costs, and actual outcomes.

The U.S. has by far the highest per capita national health expenditures and only mediocre outcomes, yet, with a little song and dance…

Soft shoe routines worked well in vaudeville, but they’re not so hot in health policy, unless your policies are designed to obtain the same results as Jackie Gleason’s famous soft shoe routine.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jow_qpHzNEk

John, has anyone looked at USA medical care spending compared to other spending such as food, housing, clothing, energy, life staples, as a percent of GDP, and then compared to other OECD?

I would contend because of our standard of living and cost of living efficiency, we spend less on these other aspects of our lives and can spend more discretionary spending on the medical care we desire. When we get a knee replacement mostly is elective.

Medical therapy vs angioplasty for CAD? Which parameter do you put at the top, 5 yr. survival vs angina control? And who makes the choice?

The answer to your headline question is ‘Yes’. The problem is that there is too much ‘moral hazard’ in the insurance-ladened US system. Because we pay on average only one-eighth of medical expenses out-of-pocket, there is no way the prices of medical services reflect their incremental value to us. Much of the time we over-consume these services, because we play the game with insurers well, while they defend against this by setting such stringent standards, that others can’t get what they really need.

Final comment: consumption rather than GDP is a better measure out of which to calculate the medical spending percentage, since it represents a better reflection of the ‘opportunity cost’ of alternative spending. As of 2009, medical spending was 21 percent of total consumption.

POST UPDATED:

The link to Avik Roy’s article on cancer survival rates has been corrected. Should have been http://www.forbes.com/sites/aroy/2011/11/23/the-myth-of-americans-poor-life-expectancy/

Sorry about that!

Yes.

Thanks for the correct link.

The argument was what I expected – a comparison of 5 year cancer survival rates. This only tells how early people got screened, not how well they get treated. It’s an almost meaningless statistic.

Here’s why: take a group of people who die from cancer at age 70. Some get screened at age 60. Their 5 year survival rate is 100%.

Others get screened at age 68. Their 5 year survival rate is 0%.

But they all die at age 70!

A meaningful statistic is aged adjusted cancer mortality, say for prostate, breast etc. That suggests how well treatments work….but it’s not included in this analysis.

As I suggested above, this article stretches too much, doesn’t pass the smell (or laugh) test.

Dr. John, It’s nice to get some explanations behind the #’s. We are learning to questions all ‘studies’, to not accept the news media’s slant on their 90 second spot.

John,

Excellent post.

2 points to consider:

1. The opportunity cost to patients of delays, and need for retreatment. The US has one of the highest worker productivity rates and GDP per worker. The US also has a high percentage of population in the workforce. The value to a patient of faster access to medical care (for themselves or for someone in their care who they would have to care for and miss work), faster diagnosis and faster cures is higher in the US than in most other countries. This productivity opportunity cost makes the value (not the cost) of medical care higher in the US and thus adults in the US are willing to pay more for quicker medical care, diagnostic technologies and new, more effective drugs. US medical care will increase its services, lower its access times, pay more for new technologies and drugs, etc., until medical costs equal value. With a higher value, the upper limit of medical spending will be higher in the US.

2. Even in a non-market price system, total cost to a patient (or caregiver), which includes the patient’s or caregiver’s opportunity cost, should approach the total cost in a market system. What is saved in the dollar payment for medical care in a managed price system will be spent by the patient in opportunity costs of access delays, need for further treatment, ineffective medicines, misdiagnosis, etc. Most of the plans to lower US medical costs are not based on productivity gains in medical treatment but are really just cost shifters that lower accounting costs in the medical sector, while increasing patient opportunity costs through delays, older, less effective technologies and treatments, etc. Too often, government and many economists, treat cost shifting as a cost savings, especially in medical care, and ignore opportunity and productivity costs as above and as you mention.

What we do get is the longest life expectancy in the world after fatal injuries are removed. We also get the highest 5 year cancer survival rates in the world. Is that worth paying for? You decide. http://www.medibid.com/blog/2011/11/the-myth-of-americans-poor-life-expectancy-forbes/

Wow! That’s an eye-opener!!

“This isn’t to say we don’t have problems. There is a lot of evidence of waste and inefficiency in U.S. health care.”

My bet is that essentially all of that is the result of government intervention at all levels (federal, state, local) in the health care market place, interfering with the correct pricing and correct delivery of health care. I am unaware of any significant waste in industries where government is nearly inactive, such as clothing or personal computers or soccer balls or ball point pens or refrigerators or fast food, etc., etc.

John;

Again, we are losing our way in the morass of so much bureaucratic bull shit. When will the non-physician business folks realize that there is no model based on business economic strategy that even comes close to the way to approach good medicine, with good knowledge that the cost of health care increases when competition is more prevalent?

Normally when competition increases, the cost of goods will come down to keep that vendor in the game. But health care is just the opposite…when a new technology hits the health care marketplace all the hospitals advertise that they are the only one that has this new technolgy and to justify their ROI, the cost goes up. The greed part of the equation is seen everywhere in our community. The cost goes up out of fear that they will be short-changed when the competition comes up with a new and better device or a better diagnostic tool. The amount that is spent on massive billboard ads as well as TV spots adds nothing to the true value of a superior physician whose main task is to transfer what he has learned in school to achieve better results. And I missed that class in medical school that encouraged us to not perform all of our efforts to deal with the patient only that which will provide him with the largest fee.

The economics of health care is all messed up, because the system rewards speed and turn-around time.

Dr. Bob

Lies, damn lies and statistics. At best, this was a nonsensical article. At worst, a grave collection of lies and mis-statements. With the corrupt American liability system and the massive infrastructure that we have developed to carry out billing, collections and audits therein…prior authorization, referral screening, drug justification to insurance companies, it is beyond belief that we would be anything but close to the bottom in terms of efficiency. For the 40 million, or whatever it is, uninsured Americans, I am pretty sure that their health care costs are close to nothing, until they die in an ER or hospital from complications of advanced “name your disease.” Most OECD countries have a single payer system, push for more generalists, suppress the over supply of specialists and cover fewer end of life care costs and high tech analytical testing with almost no liability cost. To say that the US is more efficient in ANYTHING compared to most of these countries is ludicrous.

Thought-provoking piece. We’re a New York City startup focusing on bringing transparency to the health-care marketplace, and we’re really interested in the question of costs and prices. We also see a lot of anecdotal evidence suggesting that the costs and prices are all over the map: here’s a blog post about a $1,416.51 markup on a drug that could be bought for pennies:

http://clearhealthcosts.com/2010/11/the-1481-drug-markup/

Also we’ve been collecting prices in the New York city area for cash payments, finding that an MRI can cost $400 or $2,300, and even more:

http://clearhealthcosts.com/get-info/

We’d love to know what you think!

have you tried calorie-counting? My mom is a dibtiaec and needs to loose major pounds… her Dr. suggested calorie-counting (it’s been three months and she has lost 40 pounds!!)… search calorie counters on google (or yahoo) and you can type in a food… and it will give you the amount of calories in that food! I would suggest cutting your calorie intake down to a maximum of 1500 calories per day… it isn’t easy… but tell yourself ‘this is a lifestyle choice’. also record your calories on a notebook or computer… it will help you!GOOD LUCK! Was this answer helpful?