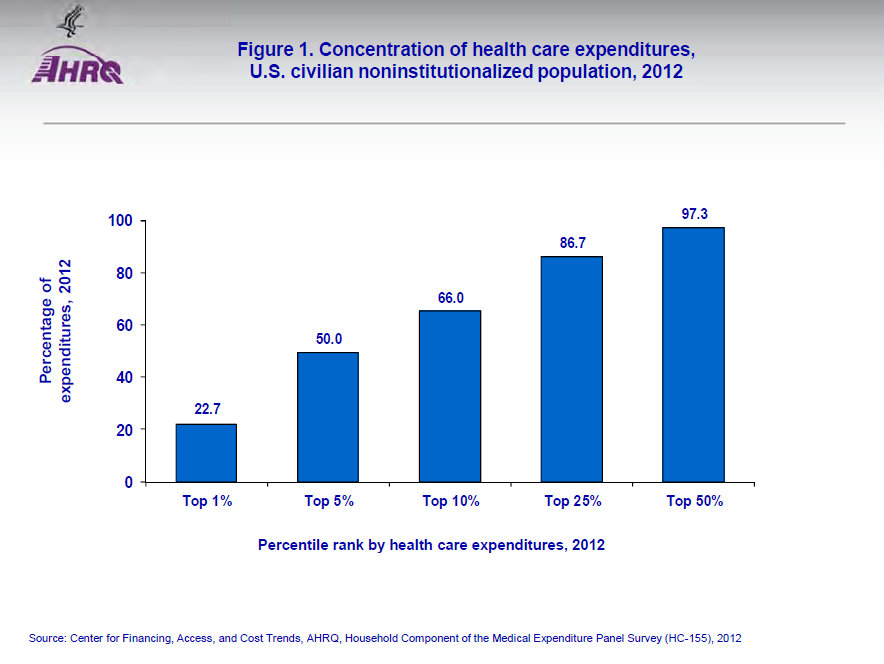

1 Percent of People Account for 23 Percent of Medical Spending

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has updated its estimate of the concentration of medical expenditures, previously reported as of 1996. In 2012:

- Total medical spending was $1.35 trillion;

- One percent of people accounted for 22.7 percent of total health expenditures, with an annual mean expenditure of $97,956;

- Five percent of people accounted for 50.0 percent of the total, with an annual mean expenditure of $43,058;

- Ten percent of people accounted for 66.0 of the total, with a mean annual expenditure of $28,468;

- Fifty percent of people accounted for 97.7 percent of the total; and

- Fifty percent of the people accounted for only 2.3 percent of the total.

This skew is important to understand for two reasons. First, it explains why “insurance” is important in health care, but why most of us should be able to happily live many years without having to interact with our health insurer until we get hit with a catastrophic illness.

Second, it prepares us for the criticism that consumer-driven health care, including Health Savings Accounts and other tools that put spending power in the hands of the patient directly, cannot control the growth in health spending. If the spending is concentrated in a small proportion of people whose illnesses are costing tens of thousands of dollars a year, we cannot get control of spending by encouraging generally healthy people to go to convenient, retail clinics instead of emergency departments.

However, this can work for higher priced services, too. When a large group’s benefit plan offered patients financial incentives to use lower priced hospitals for procedures, they save money by “reference pricing” orthopedic surgery: If patients wanted to use a higher priced hospitals, they paid the difference. American patients also take advantage of lower hospital prices in Mexico to save money.

Indeed, the more intense and expensive the procedure, the more important it is to be consumer-driven.

John- I have long promoted this as the most important number in healthcare…

Couple of additions:

1. 160 million Americans spend about $80 billion in TOTAL on healthcare in a year

2. 100% of the US Hospital admissions are by about 7% of the US population

Caveats:

While we are more likely to spend more on healthcare in our senior years, that does not mean that seniors magically become ‘high utilizers’ of healthcare

Aggregate spending numbers, when measured in the trillions, obscure the fact that, even for lower utilizers (and families where low utilizers can be together or combined with higher utilizers) $30, $50 dollars matters to US families– and why true direct pay transparency and lower regulatory costs would make a real difference to the middle class

End of life spending numbers from Dartmouth, for example, are flawed because they look at the dead population… those of us who take care of patients, in most cases, are not able to determine exactly when people enter the ‘final 3 months’ or ‘final 6 months’ of life… humility and fallibility are at the center of honest healthcare delivery.

Thank you. I believe that if we took segments of the population, e.g. all 21-year olds or all 55-year olds, we would find similar distribution.

That is: Of all health spending on 21-year olds, the top 1 percent account for about one fifth of spending.

John, I suspect you are correct, and I would add that the reasons for the expenditures would likely be very different.

For the 21-year-olds, I think we’d find more accidents. For the 55-year-olds, I think we’d find much more chronic disease.

“…the more intense and expensive the procedure, the more important it is to be consumer-driven.”

That’s an important observation. Many people tout how HSA-qualified health plans pay 100% after the maximum out of pocket spending limit has been met. This is purportedly a good thing. But, most health care spending is well above the deductible. Unless we can give people an incentive to control costs after their deductible has been met, we can never affect a significant change in health spending.

Is the problem, then, that with HSA plans the deductible is often close to the max out-of-pocket?

The problem is that HSAs create beneficial incentives to shop for medical care below the deductible (only). Most health care spending occurs in the hospital — long after patients with HSA-qualified plans have met their deductible. We need to go one step farther and create incentives to shop for care once the deductible has been met. Reference Pricing can help with that.

except Devon- remember that about 110 million Americans get insurance through a self-funded employer…

and with that, suddenly much of the spending now falls within the ’employer deductible’ (attachment point)…

structuring plan documents to incentivize patients in this environment can/will make an impact

I would think that the life time numbers would far more meaningful than these one year numbers. They would be much les skewed.

Most people could amortize a one year bill of $100,000 if they are cured and can work 10 or 20 years after that. I think that we only need health insurance because so many people have it. If we did not have it medical care would be provided by charities and people amortizing their bills after the fact and there would be much less quixotic end of life care.

Thank you. I suppose you are right, because people float in and out of the top 1%. Although, there are people who are sick all their lives and others who are healthy all their lives and then get hit by a buss. I’m sure the statistical distribution you want is out there somewhere.

I found some numbers for Canada, I would think that they would be propotional for teh USA.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2645209/

In order to calculate the distribution of lifetime costs, we estimated the Markov models using Monte Carlo microsimulation trials (Figures (Figures44 and and5).5). As might be expected, lifetime costs are somewhat less skewed than are per capita costs in any single year. However, the distribution is far from normal; costs are not tightly grouped around the mean. For women, mean lifetime costs are $89,722, with a standard deviation of $38,776. Median costs for women were $86,125. Ten per cent of women incur lifetime costs of less than $43,843. For men, the mean is $64,052 with a standard deviation of $35,331. Median costs for men were $59,819, while 10% of men incurred lifetime costs of less than $22,450.

http://un-thought.blogspot.com/2012/03/lifetime-medical-spending.html

Thank you. I believe the distribution would be about the same for any population.

I’ll make four points about this.

First, the data suggests that it pays to invest in the use of nurse case managers to help high utilizers with chronic conditions like CHF to stay out of the ER and to minimize inpatient admissions among this population. Close monitoring of weight, blood pressure and temperature which patients or family members can report daily should help. Also, house calls may be appropriate to ensure that these patients receive timely checkups to monitor their condition.

Second, it’s well known that there are wide variations among providers even in the same city in the cost of services, tests and procedures. Robust price transparency tools for use by both patients and referring doctors could help to insure that as much necessary care as possible is delivered by the most cost-effective high quality providers. Insurers can do their part via tiered network, limited network and high deductible health plans.

Third, I agree with Eric Novack that doctors can’t tell when the end of life will occur in most cases. However, I think oncologists especially could do a better job of explaining treatment options to patients and families as well as the quality of life implications of each. An honest and realistic prognosis should be offered, especially if the patient and family ask for it rather than holding out false hope at high financial cost to the healthcare system.

Finally, the primary focus of the ACA was to reduce the number of uninsured people. It’s time to shift our focus to reducing healthcare costs or at least slowing the growth rate to a level closer to the growth rate of the broad economy. To the extent that we are successful in doing that, the increase in the cost of health insurance should also slow making both healthcare and health insurance more affordable to more people.

Cooment to Eric Novack:

Thanks for your thoughtful observations. However, I am puzzled by your suggestion that saving $50 will make much difference in insurance rates.

If a health plan has 100 participants, and 99 of them choose to get a cheaper blood test, but one participant needs a heart transplant, the insurance rates for the group will still go through the roof.

I have sold health insurance and seen this happen a lot.

Note to Devon Herrick:

When you suggest that people should try and control costs above the deductible, I think you are being ideological rather than realistic.

One of the flaws of the American health system, in my rather left wing opinion, is that it expects the patient to be the kamikaze of cost control. I.e.,maybe if a few more persons choose not to get radical chemotherapy we will save money, etc.

Most other nations would move and control the price of chemotherapy instead.

I do not favor price caps for every little item in medicine, but I do favor them for the most expensive procedures.

Bob-

Apologize if I ‘under-typed’…

The point I was trying 🙂 to make was that the big numbers notwithstanding… for my real life patients, $50 makes an impact on their day to day lives– food, gas, rent, bday parties… it all makes a difference and every $50 they DO NOT have to spend matters…

And we, on the policy side, need to always go back to the basic individual patient,parent, family… and not stay stuck in the ‘mega-numbers’ that sound impressive to us in blogs, conferences, and opeds…

There was an interesting paper in Health Affairs a year or so ago that looked at the 10 million person dual-eligible population. Specifically, the authors looked at the most expensive 5% of that population that had their medical bills paid for primarily by Medicare and the most expensive 5% whose bills were paid primarily by Medicaid. Very little overlap between the two groups was found. The high utilizers among the Medicare group had chronic conditions like CHF and severe mental illness along with cancer and ESRD while the Medicaid group was primarily people in skilled nursing facilities.

In the 0-64 population, the most expensive utilizers are low birthweight premature babies, especially multiple births, those with rare diseases that need very expensive specialty drugs to keep them alive, the severely disabled who need lots of custodial care and those with CHF, mental illness, ESRD and cancer.

Several years ago, I saw a paper in the same publication that showed that in the period examined, the most expensive 5% of Medicare beneficiaries accounted for 41% of Medicare costs in any given year but they were not the same people from one year to the next. When members were ranked by cumulative Medicare claims over five years, the most expensive 5% accounted for 27% of spending. This is because some people have a serious episode like heart surgery and then recover while others die along the way.

Even among the Medicare population, the least expensive 50% of seniors account for only about 4% of costs in any given year. That suggests that routine preventive care for this population probably won’t save money while intensive management of the most expensive cases will save considerably more than the cost of the extra attention.

Thank you. One problem with dual-eligibles is that the Medicaid managers want to shove the costs on to Medicare and the Medicare managers want to shove the costs onto Medicaid.

Thanks for good info, Barry.

I am not involved in actual medical practice, so I may be wrong, but I sometimes wonder if “intensive management” would really make a cost difference for the most expensive patients age 0-64.

How can you manage a premature baby or a late stage cancer patient other than by intensive care and powerful drugs? Or in the case of a quadriplegic or late state ALS patient, other than by round the clock nursing?

I go back to my old saw that in some aspects of expensive care, maybe most aspects, the way to control costs is to set price ceilings. When the FDA approves a new cancer drug, it should act like every other health system in the Western world and set a maximum price for that drug. The same for intensive care.

We Americans keep going back to case management (in your note) or consumer choice (per Mr Herrick), because we do not have the boldness to just set price controls.

Bob,

I’m not an expert on the healthcare system either. However, I keep hearing that 75% of our healthcare spending relates to managing and treating chronic diseases. This includes virtually all of my own claims. The six major chronic diseases include CHF, ischemic heart disease, COPD, diabetes, asthma, and depression. While low birthweight babies can rack up big bills, there aren’t that many of them in the scheme of things. The same is true for patients needing organ transplants. I think case management can be quite effective for patients with one of the six listed chronic conditions. It’s not as relevant for nursing home patients, and those with cancer, ESRD, people who need organ transplants and low birthweight infants. If the Canadian experience is typical, children between 0-1 years old account for about 3% of health spending of which caring for premature babies is only a part.

I’m not a fan of price setting because it’s hard to get it right and it results in market distortions. Medicare, for example, overpays for some services, tests and procedures and significantly underpays for others. I am, however, a big believer in the value of price transparency which we still don’t have mainly because of the confidentiality agreements between insurers and providers that preclude the disclosure of actual contract reimbursement rates.

It’s also politically difficult to just refuse to pay for expensive specialty drugs that win FDA approval. At the same time, not long ago, Memorial Sloan Kettering stopped paying for Zaltrap which is used to treat colon cancer because it was twice as expensive as Avastin and no more effective. Zaltrap cost about $11,000 per month at the time and Avastin was $5,000. Four weeks after MSK made that decision, Sanofi, the maker of Zaltrap, cut its price in half. We need more of that!

Thank you. I was just speaking with a NICU nurse today who asserted that babies were kept too long in the NICU. They could go home if health insurers would pay for certain care at home, but they do not. She believed that significant savings would be made.

Eric wrote 110 million Americans get insurance through a self funded employer

Much of the spending now falls within the employer deductible

Structuring plan documents to incentivize patients in this environment can/will make an impact

Eric you are right that the employer can save money if the employees spend their health care benefits wisely

Others have pointed out how the high cost users are constantly changing

What seems relatively constant is that 20 percent of the people use 80 percent of the benefits

With Health Matching Insurance as long as the 80/20 rule holds we know each year every person in the 80 percent will use less benefits than they accrue under HMI

That means each year less money will be needed for employer reserves under the deductible or attachment point as NPLH assumes more and more of the employer’s risk with the same dollars they would have spent

A 1600 person group we wrote recently has projected savings immediately of $2 million a year

To learn more go to nationalprosperity.com

Don Levit

And structuring plan documents to include direct financial incentives based upon ‘reference style’ prices (i.e. if cost below X, company gets 50% of savings and employee gets 50%) would be powerful…

Of course, it is important to recognize that their are conditions that are very high cost that this would not necessarily impact in a meaningful way (premie babies, sickle cell anemia, early stages of polytrauma care, potentially some ca care to name a small few)…

Nonetheless, there is real opportunity to begin to shift the balance of power back to patients and families, as opposed to politicians and their pals who live deep within the world of regulatory capture or industry.

Thank you, Dr. Novack. The success so far observed in reference pricing has been for orthopedic surgery. I think for the chronic and co-morbid complex patient, it needs to be more sophisticated.

“A 1600 person group we wrote recently has projected savings immediately of $2 million a year”

Why Don, I could project such savings, too, or so could any man. But will they emerge when you do project them?

Henry IV Part I act 3 sc I.

Eric

I agree with you on the potential for real savings from reference pricing

The prices have to be carefully researched and documented

But imagine the good that can result when prices are established to benefit all parties and the need for networks and all the costs of maintaining them are abolished

John

You are right

But the employer believes savings will result

What is the downside if the employer is using the same dollars

But you are right that we will build credibility only after the real savings occur

Don Levit