Will Longer Life Expectancy Bankrupt Medicare?

Health Care Expenditures in the Last Two Years of Life

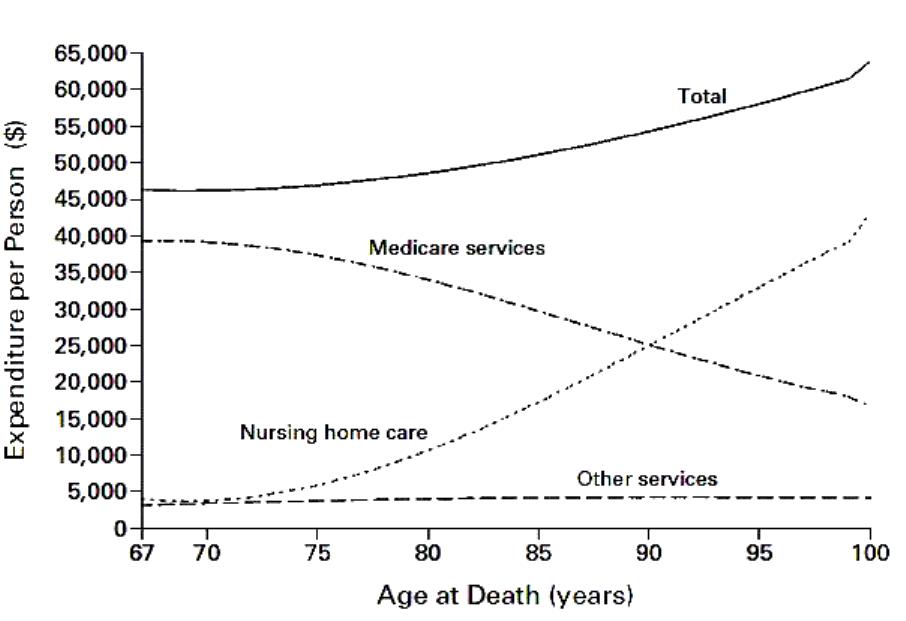

As this graph shows, the total cost of nursing home care during a person’s last two years is extremely sensitive to that person’s longevity and rises steadily as that persons attained age increases. But the cost of that patient to Medicare during those final two years actually decreases. As the article concluded, “longevity after the age of 65 has a larger effect on the costs of nursing home care […] than on the costs of services covered by Medicare.” Thus, the increasing number of persons eligible for Medicare in the future will certainly increase that program’s costs, but their increasing longevity is itself a benign factor. Or as Harvard economist David Cutler concluded, “longer life in itself will not add to Medicare costs.”

Richard Kaplan at the Health Care Blog.

That’s good news to know what longer life doesn’t translate to more medical costs. I was under the assumption that with the aging baby boomers, the cost would be unsustainable.

I wonder if there are enough nursing homes to absorb the incoming baby boomers, if not, lack of supply will mean higher prices for such services.

I concur, Wasif. I’m glad to hear that we aren’t on the hook for more.

Is nursing care cheaper relative to other medical care services Exactly what portion of health care service consumption do nursing care facilities make up?

The opening to this article: This is partly fact, partly fiction. Medicare entitlement begins when a person ages in at 65, however just because beneficiaries are living longer does not necessarily mean higher Medicare costs.

Thank god, I can feel some relief. But since we are living longer, I think we should be allowed to work longer!

This is an interesting take. I’ve read that prevention increases longevity and just pushes medical bills farther down the road. This research suggests it doesn’t increase medical bills; rather, activities that increase longevity result in higher nursing home bills.

I think I want to die at work. I don’t think I will have an identity without work. Yes, I may have an identity crisis!

As the very old population increases, the demand for residential care will likely be driven more by frailty than actual incapacity. That’s how home care assistance that allows seniors to stay in their homes can save money. Automated and robotic devices to assist them is a growing market.

More people and longer lives = More Resources

Longer, healthy lives won’t much affect Medicare.

The worrisome line on the graph is Nursing home care.

Nursing home care is presently a Medicaid expense for the most part, not a Medicare expense; but it all comes down on the same taxpayers in the end.

It’s also a cultural issue. I find it sad how isolated people can be in our culture, despite there being well over 300 million in one country. This causes elderly to be especially vulnerable to isolation.

Taylor is right. Perhaps if we were more community-based, we would be spending lots less of these types of services.

Something has to fill the void left as the role of families disappears. But whatever that is, will require more spending.

Ron, would you care to explain how being more community based would lead to less expenditures for elderly care?

I wouldn’t take this as gospel — there are always multicollinearity issues with this type of research.

I’ve seen a chart like this somewhere else and the link provided does not quite tell ncpa.org readers the whole story.

It takes a lot of work to go back to the source cited here. I think the author referenced by ncpa.org wanted it to take a lot of effort. Follow that source back to the source of this data. When you do that you will find that a New England Journal of Medicine article printed in 2000 (13 years ago) that is apparently based on 17- (1996) to 25- (1987) year-old data. Can you academics really just cite 25 year old crap like it’s gospel and get away with it in your ivory towers? Luckily they don’t let you loose in the real world

I don’t use the term “25-year-old crap” just for the blog of it. Read the 2000 NEJM article referenced by Kaplan to find out how the amount spent on octogenarians and nonagenarians is so low. The answer is apparently two-fold: (1) in 2000, the NEJM authors made up the number for many of the seniors in the Figure above (those over about age 87) because there was no data on anyone older than 87 at the time. And in making up the number for those older than 87, they of course included in their calculations the fact that for many of those made up people, there was no Medicare when they turned 65.

Talk about a pyramid of false information

In addition, because of the age of the data and the age of the NEJM article cited by Kaplan, prescription drug costs and home services are not included in “Medicare Services.” They weren’t “Medicare services” back in 1996, the year on which at least part of the 2000 NEJM article is based. Some of the NEJM analysis was based on 1987 data. Also “other services” includes Durable Medical Equipment which was not then but is now covered by Medicare.