Is Pet Health As Dysfunctional as Human Health Care?

Health policy analysts have long blamed the inefficiencies that befall the U.S. health care system to our over-reliance on third party payment. About 89 percent of all medical care is paid for by third parties — either employer-sponsored health plans, Medicare, Medicaid or individual medical insurance. Indeed, about 90 percent of the U.S. population have some type of health coverage. Thus, one could make a valid argument that medical markets devoid of insurance should function more like normal consumer markets. For instance, there is significant evidence that cosmetic medicine and corrective eye surgery both experience lower price inflation than medical care. These services are rarely covered by insurance. Another notable medical market that does not rely on insurance is veterinary medicine.

Health policy analysts have long blamed the inefficiencies that befall the U.S. health care system to our over-reliance on third party payment. About 89 percent of all medical care is paid for by third parties — either employer-sponsored health plans, Medicare, Medicaid or individual medical insurance. Indeed, about 90 percent of the U.S. population have some type of health coverage. Thus, one could make a valid argument that medical markets devoid of insurance should function more like normal consumer markets. For instance, there is significant evidence that cosmetic medicine and corrective eye surgery both experience lower price inflation than medical care. These services are rarely covered by insurance. Another notable medical market that does not rely on insurance is veterinary medicine.

A new report from the National Bureau of Economic Research, by Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein and Atul Gupta, looks at veterinary medicine. Veterinary medicine is different than human medicine in important ways. The rate of pet insurance among pet owners is thought to be less than 1 percent. There are no government programs to provide veterinary care to indigent pets or elderly pets. A logical extension of the argument that third-party payments is to blame for the poor performance of the U.S. health care system would assume pet care would function similar to the way cosmetic medicine functions. Yet, despite this theory, the authors of the NBER study found:

1) Spending on care for pets rose faster as a share of GDP during the past 20 years than medical care. 2) Spending is correlated with income. 3) There has been rapid employment growth in the veterinary sector. 4) Pet care also experiences significant spending on end-of-life care.

These are all characteristics of medical care for humans.

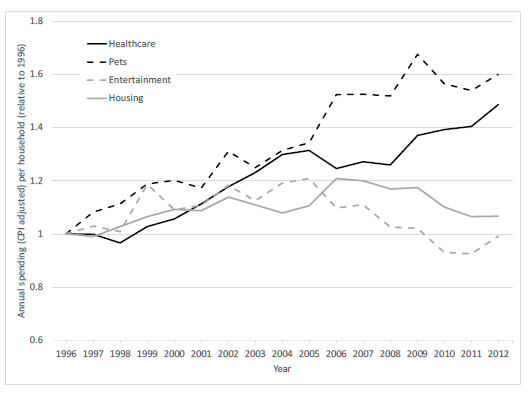

As the first figure illustrates, human health care spending increased by about 50% from 1996 to 2012. However, spending on pets increased faster — by 60%. The authors compared medical care and pet care spending somewhat arbitrarily to spending on housing and entertainment. Housing and entertainment increased modestly with entertainment acting dipping below 1996 levels finally leveling off to 1996 levels by 2012. [See figure.]

It is easy to look at the graph and identify the Great Recession. Medical care dipped briefly, housing trended down and entertainment took a nose dive. Pet care, by contrast, shot up peaking around 2009. People may have been cutting back on their own medical care, but still spent on care for their pets.

The analysis also found comparisons of spending across income groups, illustrating how pet spending and health care share similar growth patterns that are somewhat correlated to income. The richer people are, the more likely to spend on medical care — and pet care. [See more here.]

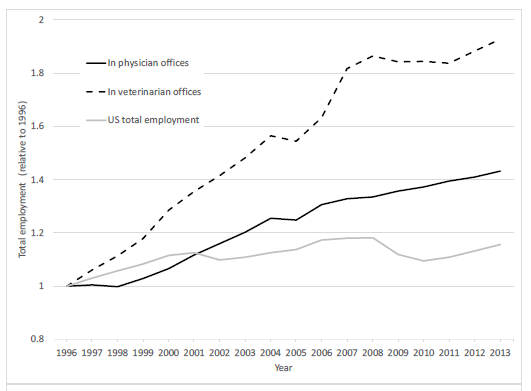

U.S. employment growth grew about 18% from 1996 to 2012. Employment in physicians’ offices grew at rates more than double that amount. Veterinarian clinic employment almost doubled during that time period. [See the second figure below.]

Finally, as a proportion of average spending, spending on end-of-life care was also much higher for dogs with lymphoma than humans with lymphoma. In the last two months of life, average monthly spending was about 50% higher than average spending for humans than prior to their illness. Average monthly spending on dogs with lymphoma was 350% higher than prior to their illness.

Discussion. Pet insurance is far less common than health insurance and the regulation of veterinary medicine is not as rigid as human medicine. Yet, veterinary medicine looks similar to human medicine in many ways. The authors suggest that some of the same characteristics that make human medicine inefficient may also make pet medicine inefficient:

- Spending is often episodic and difficult to forecast.

- The decisions are often emotional.

- Training of veterinarian is similar to medical doctors.

There are arguably other positive and negative spillover effects from human medicine to animal health. Technologies that are developed for humans find their way into pet care sooner or later.

I suspect there are other factors not explored by the authors that may also explain some of the similarities in human and pet medicine. Not only is veterinary medical training similar to physician training, the supply of veterinary schools is relatively constrained to one school in each state.

People often make trade-offs on their own medical care but may not do the same with children or pets. Parents may feel compelled to aggressively care for a pet in its final days because their children are attached to the pet. There is also an element of compassion. Pets are increasingly considered members of the family. Then there is also the old Kenneth Arrow argument: Information asymmetry. You cannot ask Fluffy where it hurts. Thus, diagnostics may consume some resources before a decision is made to stop therapy.

I would argue envy and elevated expectations may play a role. Veterinarians are addressed as “Doctor So and So.” Comparisons to medical doctors, their fees and lifestyles, may make veterinarians look for ways to tap into the concept of pet medicine as a costly service. An army of consultants tells vets how to market and adopt “best practices” from human health care. Industry consolidation, with valuation consultants brokering sales to corporate entities, is also a common occurrence.

It has been my observation (and friends and neighbors, who use a lot of vet care) that the way it often works is a veterinarian is a sole proprietor, who hires young veterinary graduates to help out. Many young graduates cycle through the practice on their way to someday opening their own shop. Fees are reasonable and care of the animal and consideration for its owner are the primary concerns. It’s a labor of love. When the vet wants to retire, he or she looks to find someone to take over. Younger veterinarians may not have the working capital to acquire an established practice so a corporate entity often acquires the firm. Corporate entities have deeper pockets, access to capital and have efficiencies of scale.

Often times a primary difference between sole proprietors and the larger, veterinary chains is experience with revenue enhancement. Basically, corporations and their consults have more knowledge about demand for veterinary care and the elasticity of demand. They know what the market will bear and understand how badly you (and your young children) want to keep Fluffy or Spot alive. After acquisitions like these, the new owners hope all the same old clients continue to patronize the vet practice, even though the prices may gradually rise and recommendations for more aggressive care interventions becomes the norm. I noticed a difference when I moved to the city from a farming community. Prices tended to be much lower in the country than in areas of the city with high median incomes.

Of course, it isn’t always corporations that learn how to enhance veterinary practice revenue. It may be a sole proprietor who begins to hire younger veterinarians and enlarges the practice. Or maybe it becomes necessary in a small practice, once the veterinarian has spent years practicing only to see revenue growth stall. The veterinarian may be a member of a country club and run into medical doctors who share stories and strategies from our dysfunctional health care system.

Shortly after my wife and I adopted an underweight rescue dog, we took her to a new holistic vet for what I thought was a wellness visit. Our dog was a picky eater and we went to seek advice on ways to boost the dog’s appetite in order to get some weight on her. About $800 later — and after checking some Internet Yelp reviews — we discovered $600 to $800 was the standard cost for a visit to this vet. Many of the Yelp comments were complaining about being blindsided by $600 bills for care. One commenter even stated that she had paid numerous bills of $600 or more and had no problem with them. But she was angry over a treatment that she thought should have gone better.

A few days later we got a call saying our dog’s blood count was odd and she needed another ($500) treatment. We sought a second opinion from another vet who though the blood chemistry was within the normal range and worked with us for about $50 to $70 a visit!

One thing I should have made clear in the post is that consumers have numerous options when selecting a veterinarian. I’ve had great ones; and I have had ones I decided to leave. Regardless of whether they are sole proprietors, small group practices or corporations, the key is how they treat their patients (and their patients’ owners).

I’ve had young vets who worked for bigger practices treat me great because they felt no pressure to “sell me” on a therapy. I’ve had young vets which I assume were working commission because they tried to sell me costly treatments they basically admitted would not likely to work.

Woof, woof woof woof woof woof. Woof woof! Meow.

Roughly translated:

“Pet insurance is expensive. However, it’s cheaper than vet bills. Meow.”

One thing that I have noticed over the years in both pet medical care and human medical care is that the costs associated with mergers and aquisitions are directly translated into higher prices to consumers. The capitol is aquired by the corporation through banks and other sources, but when you add the cost of repaying the loans, interest and margin, the consumer is the one who pays. Your article touched on this, but while the corporation gets paid through revenue enhancement, and the banks get paid in fees and interest, and the doctor’s get paid for their practice, all are paid by the consumer in the form of higher prices, triple the price of a doctor who derives his income from a practice.

My term revenue enhancement was mostly a euphemism for aggressive sales strategies and aggressive fee increases (rather than growing a business through price competition or mere expansion).

The veterinarians (or investors) who figure out an effective strategy to raise fees and over-sell services can outbid those who consider veterinary care a calling or a labor of love.

Hi Devon:

As one who has devoted over 40 years to helping the medical profession, I have not attempted to dissuade my daughter for one minute from pursuing her lifelong dream of being a veterinarian.

In my career, I have seen the corporatization of medical care and the resultant higher costs. At the same time I have watched in despair as physicians have ceded their professional stature and prerogatives to others–whether they be hospital CEO’s, employers or the “authorizers” at Medicare and health plans who second-guess care and eat up valuable hours of uncompensated time.

The result is a nationwide depression suffered by virtually all physicians I know. I know very few docs who are not dispirited, frustrated and exhausted. The notion of high incomes and Wednesday golf have been traded for a status akin to permanent residency.

By contrast, most vets I know are really happy. They get to render care without outside interference–And very few puppies sue for malpractice.

My daughter is doing what she loves. She gets to pursue a healing art and enjoy patients who don’t complain and, if she does a good job, only wag their tails or purr.

Cheers,

Charlie Bond

Hi Charlie, glad to hear it. Veterinary employment has doubled in the past 20 or so years, while pet care expenditure has shot up. According to an analysis from several years ago it’s almost entirely due to rising demand. The owner of our veterinary practice (the cheaper anecdote above, not the expensive one) spends a good part of his year living in Hawaii.

Maybe veterinary medicine needs more “fur in the game!”