What Food Stamps Can Teach Us about Health Care

There are about 50 million people on Medicaid in the United States and the biggest problem they have, by far, is finding a doctor who will see them. Yet this is actually an easy problem to solve if only the health policy community were not blinded by an overwhelming prejudice: The belief that for medical care to be accessible to low-income families it must be free at the point of delivery. In fact, the exact opposite is true. The quickest, surest way to create access to care for poverty-level families is to allow them to pay market prices.

A year or so ago I was in Boston and I struck up a conversation with a taxi driver, who informed me that she was on MassHealth (Massachusetts Medicaid). “How is it working for you?” I asked. “The biggest problem is finding a doctor,” she said. “I had to go down a list of 20 doctors’ names before I found one who would see me.”

“Were you going through the Yellow Pages?” I asked. “No,” she said, “I was going down a list that MassHealth gave me.”

Remember: this is what Massachusetts calls “universal coverage.”

Mark, a yen, a buck or a pound,

That clinking, clanking, clunking sound,

Is all that makes the world go ’round.

Not only is access to care a big problem for Massachusetts Medicaid enrollees, it’s also a problem for people who are newly insured in subsidized plans sold in health insurance exchanges. According to a survey by the Massachusetts Medical Society:

- Only about half of internists (53%) and less than two-thirds of family physicians (62%) accept MassHealth.

- Only 43% of internists and 56% of family physicians will accept patients enrolled in Commonwealth Care (state-subsidized health plans).

- Only about one-third of internists (35%) and 44% of family physicians accept Commonwealth Choice (non-subsidized health plans).

- Only about half (50%) of pediatricians accept Commonwealth Care and only 45% accept Commonwealth Choice.

What is true in Massachusetts, is also true nationwide.

I previously reported on a finding that enrolling children in the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) does not result in their receiving more medical care. But when CHIP pays higher fees to doctors, the children do get more care. Suppose the state is strapped for money and can’t afford to pay higher fees? Common sense answer: let the parents add to the CHIP reimbursement rate and pay a higher price. The obstacle to common sense: it’s illegal for parents to do this. In fact, it’s more than illegal. It’s actually criminal. [I know the doctor receiving the money could go to prison. Could the parents paying the money go to prison as well? If you know, tell us in the comments section.]

Think about that for a moment. We encourage families to enroll their children in CHIP, by making the coverage free. Many apparently drop their private coverage to take advantage of the opportunity.Then, when access to doctors declines and the time doctors spend with these patients declines as well, we make sure they have no other options. We make it illegal for the family to pay the market rate for their care!

When we expand a government insurance plan for low-income patients, we are spending billions of dollars in a way that doesn’t increase access to care. At the same time, we forbid the enrollees to do the one thing that would expand access to care.

Contrast this foolishness with the Food Stamp program (SNAP), which also has about 50 million participants. Low-income shoppers can enter any supermarket in America and buy almost anything the facility has to offer by adding cash to the “voucher” the government gives them. They can buy anything you and I can buy because they pay the same price you and I pay. But we absolutely forbid them to do the same thing in the medical marketplace.

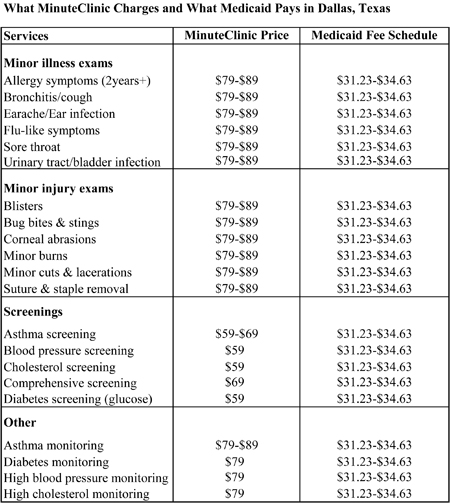

Take a look at the table below. It compares the prices charged by MinuteClinic to the rates Medicaid pays in Dallas. In general, Medicaid pays less than half. That’s why MinuteClinics usually don’t accept Medicaid. If low-income families were allowed to add from $30 to $50 of their own money to the Medicaid rate, however, in one fell swoop we could make high-quality, very accessibleprimary care available to millions of people.

Sources: MinuteClinic Medicare & Medicaid Fee Schedule 2012 and Texas Health and Human Services Commission.

Great post.

If we really want to rein in health care costs, patients have to get some skin in the game and they need to be taught how to live a healthier lifestyle. There are consequences to poor diet and a debauched lifestyle.

The big cost drivers I see in caring for patients are chronic vitamin D deficiency, obesity and poorly managed diabetes. Just addressing these three problems in the primary care setting would be a huge start.

Very insighltful. Very true.

There are several mistakes in this column.

I am the first to agree with you that the Medicaid provider reimbursement rates are at least problematic in most States and shameful (to the point of illegally inadequate) in others. (But I bet we disagree on the next steps. I think the Feds should enforce the statutory standards on reimbursement rates (sufficient to get comparable care with reasonable promptness), and I also think that providers and beneficiaries do and should have a private right of action to enforce those standards (as discussed in the recent Supreme Court case of Douglas v ILC).

But even staying within the terms of the column’s argument here, your suggested additional payment idea won’t work and misunderstands the situation. Virtually all Medicaid families and CHIP children are in managed care plans (often limited just to them without non-public enrollees). If they go out of network, the plan will generally pay nothing to the out-of-network providers, so a supplementary payment would have to equal the full cost of the service. There is, of course, nothing in law or regulation prohibiting people from voluntarily paying the full cost of the service themselves. (It sort of makes the concept of insurance pointless, but that’s not the point here.)

Keeping in mind that virtually all children and families (except in WY and AK, I think) are enrolled in managed care plans, we should keep in mind also that these plans have signed a binding contract with the state that they will provide adequate and timely services to all beneficiaries. Some State AG should be reviewing these contracts right now; if people in these plans can’t find an in-network doctor, the State and its taxpayers are being defrauded. (Note to send to Senator Grassley to look at the Texas schedule posted here.)

In turn, the States have provided assurances to the Fed that the managed care network is working and functional. Again, the HHS IG might want to look at this as potential State fraud against the Federal taxpayers.

Finally, note that some States don’t bother (inappropriately) to update their fee-for-service schedules regularly because so few of their beneficiaries are actually in a fee-for-service situation. I don’t know if that’s true for TX here, but I’ll find out. If you ever look at a fee-for-service schedule in Medicaid, be sure to check the date of the last revision.

And I’m not even getting to the question of where these people at this income level would find the money for a supplementary payment; maybe some in CHIP can, but not many. Medicaid–not even that many.

I generally learn a lot from this column that I wouldn’t learn elsewhere. I like reading it. But this one is very problematic.

Of course, the views I express are solely mine and do not represent past, present, or future employers.

TMW

Don’t you think that the next step by a government bent on enforcing Obamacare would be to tie physician licensing to a requirement tht they accept Medicaid and Medicare patients?

As I recall, a majority of physicians still treat Medicare and Medicaid patients. But, they tend to limit the ratio to a percentage of privately insured patients. I think the idea of forcing doctors to treat publically-insured patients as a condition of licensure was discussed in Massachusetts a while back.

Forcing physicians or any business to provide a service when they would not otherwise do so should indicate there’s a serious problem with the system. Why not force lawyers, teachers, or farmers to work for less than it costs to provide the service. Look at how much we could save society. Oh wait that’s different. Can you say indentured servitude…?

Lots of errors in this post. First, CHIP is NOT free. There’s an annual enrollment fee ($50 in TX) and co-pays apply. In Texas, copayments for non-preventive physician visits last year increased for those at 151% FPL from $7 to $12 and for those at 201% FPL increased from $10 to $16. Prescription drug copayments also increased from $5 to $8 for generics and from $20 to $25 for brand-name drugs. To say that families drop coverage to get CHIP completely ignores the fact you HAVE to be uninsured in 40 states to get CHIP. There are waiting periods imposed. In a state like Texas, where half of employers don’t offer coverage, it’s easy to see the need CHIP fills for kids. It’s sad to see facts twisted to fit a storyline, but especially cruel when it applies to kids.

Commenters who blithely say that states should increase payments to providers must think that states have ready access to money trees. Public programs will pay cheap rates, and it will be harder to find a doctor who will accept patients in these programs.

But – finding a doctor who will accept Medicaid/CHIP may be difficult but it isn’t impossible. Your Massachusetts taxi driver had to go down a list of 20 – so what? She found one, didn’t she? If I were on Medicaid I’d rather spend the time to search a list than pay extra, and I’ll bet your taxi driver would too.

There is no way to have easy access to all medical care for everyone who needs it; you need to stop making it sound as if there’s an easy solution. It’s CAPACITY. If everyone could pay market rates, there’d be waiting lists for appointments because the docs wouldn’t have the time.

Personally I am in favor of the UK system. You can use the NHS – no problem finding a doctor, but you may wait months to see him. Or you can pay extra for private insurance and private doctors/hospitals. What’s wrong with that?

The problem is even more severe than stated. We are on Medicare and when my wife needed a physician for her allergy, we said to forget Medicare – take us as a self pay patient and we will pay whatever the going rate would be. No one would accept this! Instead we had to go down a long list until we found a specialist who would take Medicare. What’s wrong with good old U.S. cash?

OK, maybe I’m missing something here, Dr. Goodman, but please explain why a Medicaid patient with a bug bite, as a rational economic actor, would willingly pay the difference between the MinuteClinic’s $79 fee and the $34.63 Medicaid fee, when he could go to the ER and get seen for free, assuming he places no value on the opportunity cost of a 3-hour wait?

jmitch, everybody places a value on his time. In fact, one out of every five individuals who enter an emergency room in the United States leaves without ever seeing a doctor because they get tired of waiting.

Let’s look for a second at the fundamentals that are ignored by John. When we decided that we didn’t want our fellow citizens to go hungry, we didn’t take over the agriculture and food processing and distribution systems. Instead, we left free markets in place so that they could perform their magic with regard to efficient allocation of human and capital resources. What we affirmatively did do was subsidize the needy with cash or cash equivalents so that they could enjoy the fruits (haha) of the free market. Why not take the same approach with health care? Subsidize the needy with cash deposited into HSAs in the recipients’ names, the amount determined by a sliding scale based on income, then allow them to purchase whatever sort of health care arrangements they prefer whether expensive major medical plans or inexpensive high deductible catastrophic coverage. Default them into state pools of the latter if they choose to do nothing. That approach has several advantages: it creates rational incentives for prudent consumption, it reintegrates the roles of payer and consumer of health care, it encourages transparency in pricing by providers, it creates tens of millions of lay accountants to scrutinize billing for fraud and overcharging, it disentangles health care from employment and so on.

Re: jmitch comment at April 11, 2012 at 11:57 am

I agree with Goodman that everyone puts a value on time. But even if this economically rational individual did not, the law is not what seem to think it is.

Medicaid beneficiaries can be charged a copayment for non-emergency use of an ER (even an ER within their managed care network (which almost everyone is in; see my previous comment). The CMS guidance on this copayment is clear, and hospitals definitely know about it.

And, given the limited disposable income that Medicaid beneficiaries have, it would seem to me that this copayment would be especially salient in making these decisions.

TMW

Like Michael an HSA-like debit card Family Medical Account state controlled with little or no cash gap access into major insurance coverage (by the state)coordinated by a TPA would avoid the enormous expense of HMO overhead and give ownership to families. As Joe V. Kennedy wrote: “Government policy is far more effective when it channels market forces than when it overrides them”. Individuals owning and controlling the resources that the government shares with them are likely to be prudent, while gaining equity in choice of medical care access and quality.Bob

For Eliz Reid: You are an MD? Where do you practice? For every Medicaid patient I saw in the office, for every Medicaid patient I took care of in the hospital, I received less in reimbursement than my overhead cost. Therefore, I was contributing charity, for which I received no tax credit. It was a loss which had to be offset by other income I earned. I did it because I wanted to take care of patients, period. But forcing me to accept Mcaid or Mcare as a condition of licensing would be equivalent to forcing a gas station owner to accept 85 cents a gallon from every “Gasicaid” (hypothetical govt program) customer who drove in to his station. He soon would go out of business. Unfortunately, and progressively over the past half century, being a physician has had the dual role of physician treating patients and (unfortunately) small businessman.

Joann has (to me) the right idea. Make it a two-tiered system (Medicare). The problem, Don, which you experienced first hand, is that everyone (unless still employed and covered by yours or your spouse’s plan) is forced into Medicare at age 65. You have no option to buy pvt insurance (if you go with a Mcare Advantage plan, such as United HealthCare, etc, Mcare and its price schedule still regulate which doctor you can go to, and how much they are paid). If a physician who is a Medicare “provider” accepts one dollar over the fee schedule, he/she may face a fine (roughly, as I haven’t reviewed this recently) of $10,000 and is prevented from seeing Mcare patients for two years. A new system with private availability and vouchers and Health Savings Accounts and more reasonable reimbursement would lower costs and increase availability.

Plus, Congress(ional Democrats) and Obama passed a bill which takes $500 billion from Medicare. Were that bill to become law, you would not be able to find enough doctors to see patients.

Re: Karl Stecher comment, April 11, 2012 at 6:16 pm

First, let me say that I admire your willingness to take Medicaid patients even though the low reimbursement rates meant that you were taking a loss. It’s a sad thing that these rates cannot even compensate a physician for his/her work. As my 9:47 post on this column makes clear, I think that’s not only shameful but also illegal and also (depending on whether this is a managed-care setting) possibly fraudulent. The fact that physicians like you would still see these people is the main reason that they get adequate care in some States.

I do, however, want to clarify a couple of different points that you make.

First, no one is “forced” to go into Medicare Part B (i.e., the physician payment side of Medicare). It’s an entirely voluntary program. You can even opt out of it once you’re enrolled. The “force” in this case is the private insurance market. No commercial insurance company will write individual coverage (or even small-group coverage) for people who are over 65. If they did, they’d probably place so many limitations on the payments under the policy and would probably make the cost-sharing so high that the actual insurance value you’d get would be very thin. That’s how insurance markets necessarily work because of concerns about risk and adverse selection. (This is even more true for the other people eligible for Medicare: people with disabilities, people with kidney disease, and people with ALS. I doubt those people can get insurance at all in the private commercial market.) I concede that this is a real “force” to be reckoned with by an individual, but the comment might have left people believing that the “force” was a legal requirement, not a result of the business model of commercial insurers.

Second, you allude to a Democratic/Obama supported piece of legislation that “takes $500 billion from Medicare.” I assume that you are referring to the cuts that were included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

I want to make three clarifications to that comment. First, if you look carefully at the Medicare cuts that were in the ACA, you will find that none of them affected physician reimbursement rates. None.

Second, if you read the fine print of the budget just adopted by the Republican-controlled House (authored by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI)), you will find that these ACA Medicare cuts appear to be maintained in the future, even as the expansions of the ACA are assumed to be repealed. Mr. Ryan seems to support the cuts that went into law with the ACA. (That still doesn’t mean that they’re physician reimbursement cuts.)

Third, the major legislation cutting physician reimbursement rates was the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. (That law was authored by then-Congressman John Kasich (R-IL) who is now the Republican Governor of Illinois. Mr. Gingrich was the Speaker of the House and Mr. Lott was the Senate Majority Leader. As is probably obvious, the Republicans controlled both chambers of the Congress. As is also obvious, the President was Bill Clinton, so this is indeed a bipartisan law.) That law created the now-infamous Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) and was praised for the billions of savings/cuts it would create in Medicare physician fees in the future. It is that same SGR that runs out at the end of this calendar year and that will, if not postponed, cut physician fees in Medicare by 30 percent in one fell swoop.

I believe that the Congress and the Obama Administration will find some way to postpone these SGR cuts once again, and I am glad of that (as I assume you are). But I also want to point out here (as I have elsewhere) that this allows politicians to have their budget cake and eat it, too. Republicans (and Clinton) got to crow victory about the savings in 1997 but then the Congress (no matter who’s in charge) postpones the sacrifices each year by a little bit longer. This is sham budgeting. Someone should have the courage of his/her budget convictions and either enforce the unpopular cuts or raise unpopular revenues to eliminate the cuts.

Again, the views I express are my own and should not be construed to represent past, present, or future employers.

Tim, you are not correct about the Medicare cuts under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). An independent commission is charged with reducing the spending and about their only option is to reduce provider fees.

As we have reported before at this site, Medicare’s Chief Actuary predicts that with in 8 years, Medicare fees will be lower than Medicaid’s fees. One in seven hospitals will leave the market and the elderly and the disabled will have severe access problems.

First of all, physician reimbursement is so bad, most doctors won’t take it. Same with medicare. The mayor clinic/hospital in Phoenix has totally opted out of medicare. The whole issue is not about doctors, it is about earning a living. I find it ridiculous to solve the problem of poverty level folks on welfare by making them pay “market price” whatever that means. However, I do feel very strongly that everyone should pay something for health care, especially when they can afford cigarettes and cell phones. The insurance industry has done a huge disservice by lumping all doctors in primary care and paying all docs the same fee (inadequate) regardless of any markers to check ability, learning and knowledge, experience. This has done more to devalue the medical profession in the eyes of the consumer. You can buy a Zegna or Oxxford suit for $3500, or a Jos. Bank one for $600. Tell me that there is no difference because all suits should pay the same amount.

Dr Bob Kramer

Re: comment posted by John Goodman on April 12, 2012 at 6:16 am

John,

I didn’t realize that The Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) was what was under discussion when Mr. Steicher expressed his concern about Medicare cuts. In the context of his comment, I assumed he was talking about specific cuts to physician fees (on which I still think I am right: there are none in ACA). My apologies for the misunderstanding.

But I would make a few clarifications to your response to me about IPAB. First, the IPAB provisions come into effect only if the growth in health expenditures exceeds target rates. You and I both know that estimates are just that—estimates, but it bears noting that while the Medicare Actuary projects that spending will exceed the trigger targets and the provisions will come into effect, CBO most recently projects that spending will not exceed the target and that they won’t. (On top of that, of course, there a lot of actuaries whose studies have been paid for by interested participants. I, myself, prefer to stick to the ones at CMS and CBO; that’s more than enough ambiguity in estimation for me.)

Second, the places that IPAB will turn to get cuts/savings are unspecified. There is no required targeting of physicians, hospitals, drug companies, etc. That, of course, leaves everyone fearing that their favorite Medicare spending will be the one that gets cut, but there is no real answer at this point. (I, myself, don’t like laws, regs, sequesters, or doomsday machines that command cuts/savings without making specific what their source will be. That allows politicians of all stripes to claim victory before they’ve even asked for sacrifice, much less won the fights. If they want credit, they should give the details.) But in any event, it’s unclear where the cuts will be if IPAB is triggered scenario.

Third, the IPAB trigger targets are actually lower than those Medicare targets included in the Ryan Budget recently adopted by the House. They’re both complicated plans with phase-ins, but eventually the IPAB targets settle at GDP growth plus one percent. The House Budget eventually settles on GDP growth plus half-of-one percent. Again, by shielding specifics behind the premium-support/voucher proposal for Medicare, the House budget is unclear about what gets cut, but I would argue that what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. If one assumes IPAB will cut one’s favorite spending, one should assume Ryan does, too, only more so. Or assume neither. Or ask for specifics.

Finally, I would say that I personally don’t like IPAB because it is essentially the Congress and President delegating to another entity what should be their real work. My friends who support IPAB point to the years of Medpac making thoughtful recommendations for slowing Medicare growth only to have the Congress and President ignore them; they also point at the SGR debacle as evidence of what Congress will do on its own. But I think politicians should have the courage of their convictions and not simply hand the hard stuff off to others.

The views I present are, of course, my own.

For Karl Stecher: I agree with your analogy about being forced to take less money for gas. I also think that, like frogs subject to gradually increasing water temperatures, physicians could one day wake up and find that the water has boiled around them and that the powers that be have found it necessary to enlist them involuntarily in a system that has ensnared a majority of the population.

Regarding my credentials, I am a neurologist. Used to practice in Minneapolis, wrote a few things back in the early 90s about the changes in practice we were seeing there, loved educating my patients, but disliked the drug mentality pervading medicine and the diminishing value accorded to the doctor-patient relationship. I switched to writing. I’ve written the health column for The Elks Club Magazine for the last 6 years – the editor likes education, and gives me enough space and freedom to do it – and it has a circulation of about 900,000. Moved to Colorado last year.

I’m in my late 50s and this touches on a lot of my fears (concerns).

1. IPAB, or any other medicare cost containment will use some combination of: (a) cuts in reimbursement rates, so it will harder and harder and I will have to travel farther and farther to find a doctor who will treat me under medicare; (b) cuts in covered services (no more heart by pass surgeries for patients over 85.)

2. I can’t solve this by paying for things myself, because of regulations that forbid it.

The income-graduated voucher for insurance coverage is a good solution. But it will always be characterized as “they want to take away your medicare”.

Probably the best thing I can hope for is that Medicare will cover a sure-fire painless form of self-administered euthanasia.

In re comment by molly on April 12, 2012 at 2:24 pm:

I, too, am in my late 50s and I have a lot of concerns, but i don’t think it’s going to be this bad any time soon–if ever. Medicare is not turning into the Hunger Games yet.

If IPAB goes forward (a big “if”, given current political currents) and if growth rate in Medicare is high enough to trigger cuts (an “if” that reasonable actuaries can differ on), then I would expect IPAB to make recommendations for cost containment that are similar to those already made by Medpac (and largely ignored by the Congress). They’re not so apocalyptic; they’re mostly incremental. I like some and oppose others; I’m sure other readers of this blog have differing opinions. But there’s no reason to turn to what you refer to as “self-administered euthanasia.”

Dr. Goodman: RE: “In fact, one out of every five individuals who enter an emergency room in the United States leaves without ever seeing a doctor because they get tired of waiting.” Really? That’s news to me. I can see how some urban hospitals (?Parkland) might have a 20% LBE rate, but I highly doubt that’s the national average. At my busy ED (90,000 annual visits), it’s less than 2%. I see Medicaid patients all the time who come to the ED for non-urgent problems because they don’t want to pay the copay to see their doctor.

Tim Westmoreland: RE: “Medicaid beneficiaries can be charged a copayment for non-emergency use of an ER” Yes, that’s true, they *can* be charged a copay, but they rarely pay it. Why should they? – what’s the incentive? And how do you define “non-emergency” before they have their mandatory medical screening exam?

As acupuncturists we have to study Chemistry, bicrtemishoy, all levels of Human Disease processes, all body systems of the biology of the human body, anatomy and the tcm subjects along with precise point location, Nutrition the list goes on, it’s damn hard. Some general practitioners have swapped over to this tcm modality and admit that even they with thier western medical training find the degree in acupuncture very hard. Acu is soon to be one of the most widely accepted complementary medicines