Sorry Dartmouth, Geographic Variation in Medical Procedure Rates is Not Unique to the U.S.

The Dartmouth Institute maintains that large variation in the use of various medical procedures demonstrates the inefficiency inherent in the way that the U.S. health care system is organized. The mere fact that variation exists also means that the U.S. system is inequitable. If procedure rates vary, some people have too little access to medicine while others have too much.

Members of the Dartmouth group also claim that “geography is destiny for Medicare patients.” Its Dartmouth Atlas Project claims to show that although Medicare spends more in areas where there are more hospital beds, physicians overall, and specialists per capita, people do not get better care.

If one believes these claims, then the solution to U.S. health care spending is to remove decision making power from individual patients and physicians. Instead, government should have the power to forcibly equalize treatment and resource use everywhere in the country. Fortunately, a large amount of evidence suggests that the Dartmouth Institute interpretation leaves much to be desired and that it is possible that government control is more likely to be the problem than the solution.

For example, this 2010 Dartmouth Atlas Surgery Report from the Dartmouth Institute made much of the national variation in Medicare hip replacement rates in 2000-01. Noting that the rate ranged from 1.2 per 1,000 in the hospital referral area of Alexandria, Louisiana, to 6.7 per 1,000 in the hospital referral area of Boulder, Colorado, it concluded that

[b]ased on the data presented here, it appears that patients in some regions and among some populations may not be getting adequate access to the procedures, while patients in other regions and among other populations may be undergoing the procedures at higher rates than necessary.

Reaching such a conclusion from local hip replacement rates requires assuming that the U.S. population is composed of identical people identically distributed over a featureless geographic plain that is everywhere the same.

Unfortunately, the Dartmouth report failed to inform readers that the most common reason for hip replacement is osteoarthritis and that it is well known that the prevalence of primary osteoarthritis of the hip occurs at much higher rates in Caucasians than in other population groups. In 2010, the proportion of blacks or African Americans in Alexandria, Louisiana, was 57.3 percent. In Boulder, Colorado, it was less than one percent. Hip replacement rates also vary with age, comorbidities, socio-economic group, and employment history.

Indicting the U.S. health system for varying procedure rates also fails to address the fact that hip replacement rates vary by country even when the countries in question have centrally controlled, government run, health care systems that deliver precisely equal treatment, at least on paper.

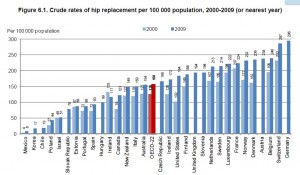

The following graph is from a 2013 OECD working paper by McPherson et al. It shows that in 2009 the hip replacement rate in Germany was more than 17 times that in Korea. Within the G-7 countries excluding Japan, the German rate was 2.5 times that in Canada.

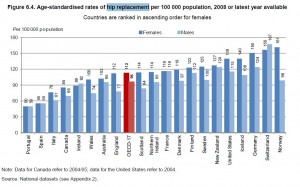

As the second graph shows, things change a great deal when rates are adjusted for population age. Age is important for the obvious reason that people over 50 are more likely to need a hip replacement and the probability of needing one goes up when people are in their 80s. The age standardized rates in Norway are more than 3 times the age standardized rates in Portugal. Among the G-7 countries minus Japan, the rate for women in Germany is almost 2 times that in Italy.

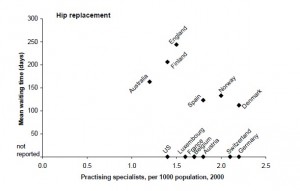

The third graph, from an OECD paper by Siciliani and Hurst, shows hip replacement rates as a function of a nation’s number of practicing specialists in all specialties.

It provides a tiny piece of evidence suggesting that the mere existence of specialists may not be quite the spending driver that Dartmouth says it is. Although the US had a relatively low number of practicing specialists in 2000, it ranked 5th in age-adjusted hip adjustment rates a decade later. Spain, which had a middle ranking in specialists, was next to last in the hip replacement rate ranking.

Although France has the highest rate of hip replacements, it is in the lower half of practicing specialists per 1,000 population. Australia has fewer specialists per 1,000 than the US but does more hip replacements.

Note that none of these graphs addresses waiting lists. In 2000, Siciliani and Hurst calculated that people who had already been approved for hip replacement surgery faced an average wait time of 244 days in England, 206 days in Finland, and 163 days in Australia. Some evidence suggests that people who have to wait for surgery incur higher economic costs and worse outcomes. (See this, this, this, and this for examples.)

“If one believes these claims, then the solution to U.S. health care spending is to remove decision making power from individual patients and physicians. Instead, government should have the power to forcibly equalize treatment and resource use everywhere in the country.”

A very scary thought, but I think that may be the ultimate goal.

I can concur in part with your contention. But I suggest your argument regarding hip replacement occurring more often amongst an older population is clearly true – and you do mention the age difference in your international comparison – without doing any research at all I would guess that Boulder – being the site of a major university – would not tend to have an older than average population – so the question not asked is why is Boulder’s hip surgery rate so high if, in fact, it is a relatively younger population?

Alexandria, Louisiana, is the site of Louisiana State University. It enrolls roughly the same number of students as the University of Colorado at Boulder.

The two parishes the Alexandria MSA covers have a couple of percent more people over 65 than Boulder County. Not much of a foundation for concluding that variations across local areas show that individuals make poor health decisions and need to be governed from above.

I am not “arguing” that older people are more likely to need hip replacement. I’m simply reporting what other people have concluded. Maybe a lot of people in Alexandria go elsewhere for hip surgery while other people choose Boulder. We don’t know.

The fact that similar variations occur in countries other than the US makes it unlikely that the US variations are the result of inefficiencies unique to US health care.

Linda one of the principal findings of Wennbergs and Capers research is that groups of people with very similar demographics nevertheless can demonstrate wide geographic variations in medical usage. The variations were not found to affect all procedures, but were pronounced in roughly the same subset of procedures across different geographical locales.

The two reaserchers theorized that difference arises because of physician preferences and practice behaviors – not becaue of demographics.

I do agree with you – and with Wennberg and Caper – that patients need more information, and need to be more involved in decisions relating to their care. That was their recommendation starting in the 1980s. I have not seen a compelling argument that they were wrong,

John,

I’m not addressing Dr. Wennberg’s work in this post. The quotes come from specific Dartmouth Institute publications. However, you might take a look at Greg Scandlen’s discussion of one of his early studies at http://healthblog.ncpathinktank.org/myth-busters-3-hysterectomies-in-lewiston-maine/.

In general, I think I’d argue that some practice variations are a function of the state of knowledge. As evidence improves variation declines, all else equal. After all, there is ample evidence to suggest that evidentiary findings diffuse rapidly. But it does not follow that improved evidence leads physicians to follow existing practice guidelines. Some of them have rather shaky evidential foundations and patient characterists are not identically distributed.

“I think I’d argue that some practice variations are a function of the state of knowledge”.

In general, that is no doubt true at some level. Still the state of medical knowledge certainly advanced between 1950 and 1980 and yet Wennberg et all first began to cite variations around 1980.

So I think there’s more to the story than the continuing advancement in medical knowledge.

Note I’m not disagreeing with your main post – just suggesting the findings of Wennberg et all are still relevant, and (I think, anyway) for largely the same reasons.

Sorry, not to disagree but LSU is in Baton Rouge, about 90 miles away. Alexandra is a poor town, near a military base.

Yes, my mistake. Thank you for the correction.

This is a Medicare study. Although Boulder has a large young population, very few of them are on Medicare as that requires you to be either 65 or disabled.

One big factor in Boulder is the reality that the elderly folk here are very active and hike and ski. I know a 91 year old who cross country skis at 11,000 feet and an 86 Y/O who climbs 18,000 foot mountains.

I don’t have the data but I would speculate that the Medicare population in Boulder is actually older than the Medicare population in Alexandria.

Were we directed from Washington when to sow and when to reap, we should soon want bread. Thomas Jefferson.

Were we directed from Washington for our medical care, we should soon be sicker or dead. Kent Lyon, plagiarizing freely from Thomas Jefferson.

If you did deeper into medical spending, it varies not just by region, but also by income, sex, age, ethnicity and by insurance status. That should not come as a surprise. Virtually all goods and services vary by a range of attributes and demographics. That is why patients need to take more responsibility for their own medical decision-making. It is well known that men don’t like seeing the doctor. If women, for example, want to see the doctor more than men, that should be their prerogative. It should also be their expense.

More than 30 years ago I was privileged to meet with John Wennberg and Phil Caper in regard to a project with them that my company was funding.

Wennbergs studies of geographic variations in medical care delivery were already well-known.

I distinctly remember Wennberg mentioning that he had found the same kinds of variations in France. I don’t recall him mentioning any other countries at the time.

Whatever

Whatever, it is certainly no surprise to find that others are saying that variations Wennberg was finding at that time have been found in other countries. It makes sense because they are a product of physician behaviors.

Btw, the notion to “remove decision- making power from patients and physicians” is diametrically opposite of Wennbergs recommendations.

I also heard and met Dr Wennberg( I think in the early 90’s) when I was a medical director of an HMO. I recall that he was also promoted the concept of Informed Patient Consent, a series of programs covering conditions such as breast cancer and prostate cancer. His hope and that of his collaborators was that, if the patient and his/her physician reviewed this information produced by Dr Wennberg et al and had an informed discussion about it’s contents, then the patient could make a better decision about whether to proceed with a treatment or procedure.

The hope was that this would contribute to a decrease in variation and, because his target market was the managed care industry (HMOs) a decrease in utilization(or the total number of procedures)

Looking back I think the product was a failure; in part because the technology was ahead of it’s time and in part because, as the economy improved into the nineties, people became less concerned about cost containment. With that said his basic research on variation was and is valuable in trying to understand why variation occurs and in trying to affect health care costs.

I have to agree that the research is valuable, although I differ with the policy conclusions of the Dartmouth team. They are an outstanding group of committed professionals.

Linda,

Thank you so much for contributing to the conversation on health policy. I’m not sure you made a strong point other than to discredit the Dartmouth report. I’m having trouble grasping your point. What does this mean, that there are variations in utilization? other than the fact that their methods and logic are flawed- bring it home for me.

The biggest issue I see is that they are only using MEDICARE data, and that may not accurately reflect the absolute number of total hips being performed. There are some joint replacement surgeons that don’t even accept Medicare because the reimbursement is so low compared to private insurance.

I think anytime you discuss variation across the country (US) you must also tie in the WILDLY drastic variation in price for Total Hip Arthroplasty:

http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1569848

I think this has little relevance to your article, but I wanted to clarify that LSU is located in Baton Rouge, LA. The undergrad enrollment there is close to 30K, very similar to UC at Boulder. The satellite campus of LSU in Alexandria post enrollment numbers just over 2,000 students.

http://lsu.edu/

Thanks!

Linda and Friends…

One thing stands out–the pre-existing biases of the researchers. If you want to “prove” that the health care system has unexplained variations in performance, you look to data that are normally collected, then you sort the data to demonstrate that, indeed, there are geo-graphic variations, from which you conclude that there are inefficiencies in the system that need correcting. Why would not researchers start with an assumption that people/patients and providers/payers vary a great deal, so the incidence of procedures would also vary. This variation picture should not be interpreted to mean inefficiency but “patient-focused care” something we allege the healthcare system wants to promote.

Beware of the larger pot of data coming as a result of the implementation of EMRs. Will all variations in care for particular diagnoses and guidelines mean low quality care? Believe me, many bureaucrats will allege that, as it justifies their power grabs via regulations.

Just wait until ICD-10 is fully implemented. Too much data is as bad as not enough.

Here is a point of view that we should take to heart…

“Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?”

The Rock, T.S. Eliot 1934.

Wanda Jones

San Francisco

Can we also look to the fact that old folks in small town, Deep South Louisiana are more obese than wealthier per capita, more healthy and less obese Boulder Colorado.