Selling the Same Thing for a Different Price is Normal Market Behavior

Understanding the price of ketchup may go a long way towards explaining why mainstream health reformers give such bad reform advice.

Per capita health spending varies a great deal. It varies by geography, it varies by health status, it varies by demographics, and it varies by individual patient characteristics. Academics and government officials decry this variation. They think that health care spending and utilization should be the same everywhere. Despite ritual hand waving about the importance of clinical differences, their policy recommendations generally attribute variation to inefficiency, overuse, and waste.

As inefficiency, overuse, and waste are bad, reducing variation, any variation, has become one of the lodestars of mainstream health policy. Obamacare’s insurance provisions were designed to reduce variation by standardizing individual insurance. Its competitive effectiveness research provisions will reduce treatment variation by standardizing individual treatment. Its ACOs will reduce delivery variation by standardizing the structure of medical practice. Its payment reforms will ensure that all services are paid for in the same way.

Systems controlled by central planners tend to prize administrative simplicity. They standardize everything in order to reduce complexity. They require clients to fit the system. The usual result is fewer choices, higher costs, and tremendous administrative friction.

Markets vary the systems to fit the clients. Private markets thrive on variation. They accommodate diversity by letting suppliers and those who use their products tailor individual products, prices, and contractual arrangements.

Mainstream health policy would be a lot more useful if its adherents would realize that price variation is normal, stop trying to arbitrarily squash it and start thinking instead about how to give patients the power to control costs by controlling who gets paid. The reason is that even the simplest products sell at different prices in the same area because those who buy them vary in their location, their shopping habits, and their willingness to trade time for money.

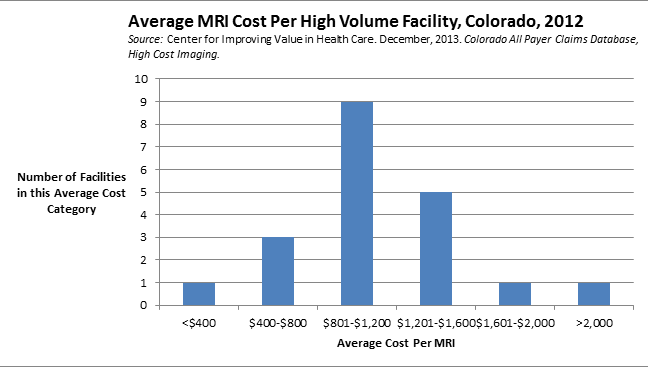

Think this is nonsense? Here’s the variation in average cost per service for MRIs done at the 21 highest volume MRI facilities in Colorado in 2012, a variation that at least some people think needs to be tracked and controlled:

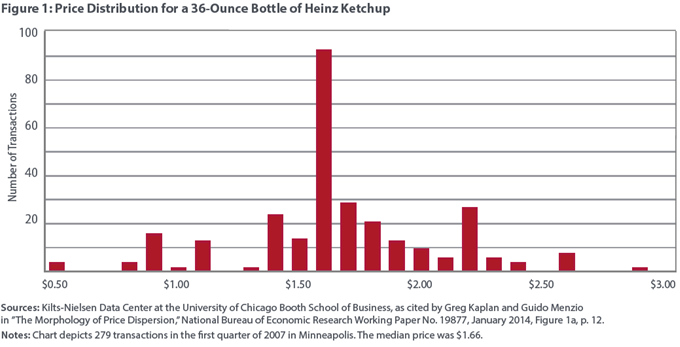

Here’s the variation in cost for 279 purchases of a 36-ounce of Heinz Ketchup in Minneapolis in 2007 from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond’s July 2015 Economic Brief. If the cost of a 36-ounce of ketchup varies this much, why shouldn’t MRIs?

Thanks, Linda!

This is an interesting piece on price discrimination. The only thing that concerns me about wide variation in medical prices is the perverse incentive OPM — other peoples’ money — has on the decision to buy.

With respect to ketchup, people are buying it at different prices for a variety of reasons. A mother buys hotdogs for dinner at the grocery store and realizes they’re out of ketchup on the way home. She swings by 7-Eleven and pays $3.50 for the convenience of not driving back to Walmart. Maybe she is at Krogers because they have a sale on meat and she doesn’t want to stop elsewhere just for cheaper ketchup. (For that matter, maybe she buys Heinz because her kids gripe when she buys Store Brand ketchup.)

I don’t have a problem with people who buy Heinz ketchup at 7-Eleven any more than I care if someone pays $100 more (out-of-pocket) to see Doctor Adams, rather than Doctor Brown. I’m a little more concerned when an MRI is $2,000 more expensive at Hospital A than Radiology Clinic B — if the price disparity is because consumers doesn’t know there is a difference and don’t have an incentive to ask about pricing.

If search costs are a high percentage of the cost of the goods sold and a high percentage of potential cost savings there will be little incentive to search for and seek out lower cost sellers or substitutes of the item. Ketchum falls into this category since it is a lower cost item and search costs for cheaper ketchup will erase the potential cost savings. The selling price of ketchup should have a high standard deviation. MRIs are expensive relative to search costs and potential savings, and should have a lower standard deviation of their selling price than ketchup. The problem is that most consumers do not benefit from undertaking a search for a lower cost MRI because insurance or the government is paying the cost of the MRI. If consumers had an incentive or benefit for seeking out a lower cost, MRI, they would and the standard deviation of the cost of MRIs would shrink from the competive pressure of consumer preference.

Thank you. That is very well put.

There is nothing wrong with price discrimination as long as the buyer has transparent price information in advance of committing to the purchase and perceives incremental value in exchange for a higher price.

In the case of the ketchup example, convenience has value whether it’s being able to get in and out of the store quickly or finding a seller close to home which saves both time and gasoline vs. a more distant alternative. For airlines and hotels, customers may opt for a non-refundable rate booked well in advance in order to save money as opposed to booking at the last minute and paying a higher price but being able to cancel without penalty if needed.

For the MRI example, assuming there is no material difference in either the quality of the equipment or the competence of the radiologist interpreting the image, it’s hard to imagine that anyone would knowingly pay several times more than necessary at a hospital to get a scan that can be scheduled well in advance vs. a much lower price that an independent imaging center would charge. Of course that assumes the patient is spending his own money and can get accurate price information ahead of time. If insurance is paying and the deductible was met and there is no difference in the copay, the patient isn’t likely to care one way or the other.

At the very least, if we expect patients to make informed choices about where to get care, they need accurate price and quality information that they can rely on in advance of committing to the service, test or procedure. Such transparency remains glaringly absent in healthcare and both providers, especially hospitals, and insurers seem to prefer it that way.

Check out Ralph Weber with Medibid

Don Levit

The MRI example may be somewhat compromised, in this sense:

Look in detail at the facility which charged the most:

a. how many customers did they have?

b. where did those customers come from?

c. how much money did they actually collect?

If the facility charging $2100 actually collected $600, and the facility charging $600 actually collected $600…….

then what?

When it comes to Medicare, the $600/$600 scenario happens all the time.

The $2100/$600 really does matter for the uninsured and those with high deductibles. For this growing minority of patients, we do need firm consumer protection laws. My preference would be a statute that requires a provider to give a binding quote before scheduled care. If the patient ignores the quote, any extra cost is on them.

Many patients of course will not ignore the quote, and the high priced facilities will have to defend their product in the way that Linda Gorman describes.

This is a very good point. However, there are very few highly priced goods for which the transaction price is as transparent as a bottle of ketchup. I doubt there is a market in the U.S. in which retail customers negotiate for individual bottles of ketchup.

However, the variance in charges by MRI facilities should cause no more disturbance our sense of outrage than the variance in charges for automobiles or hotel rooms or whatever else where transaction prices differ from posted prices.