On the Anti-Cash Bias in Health Care

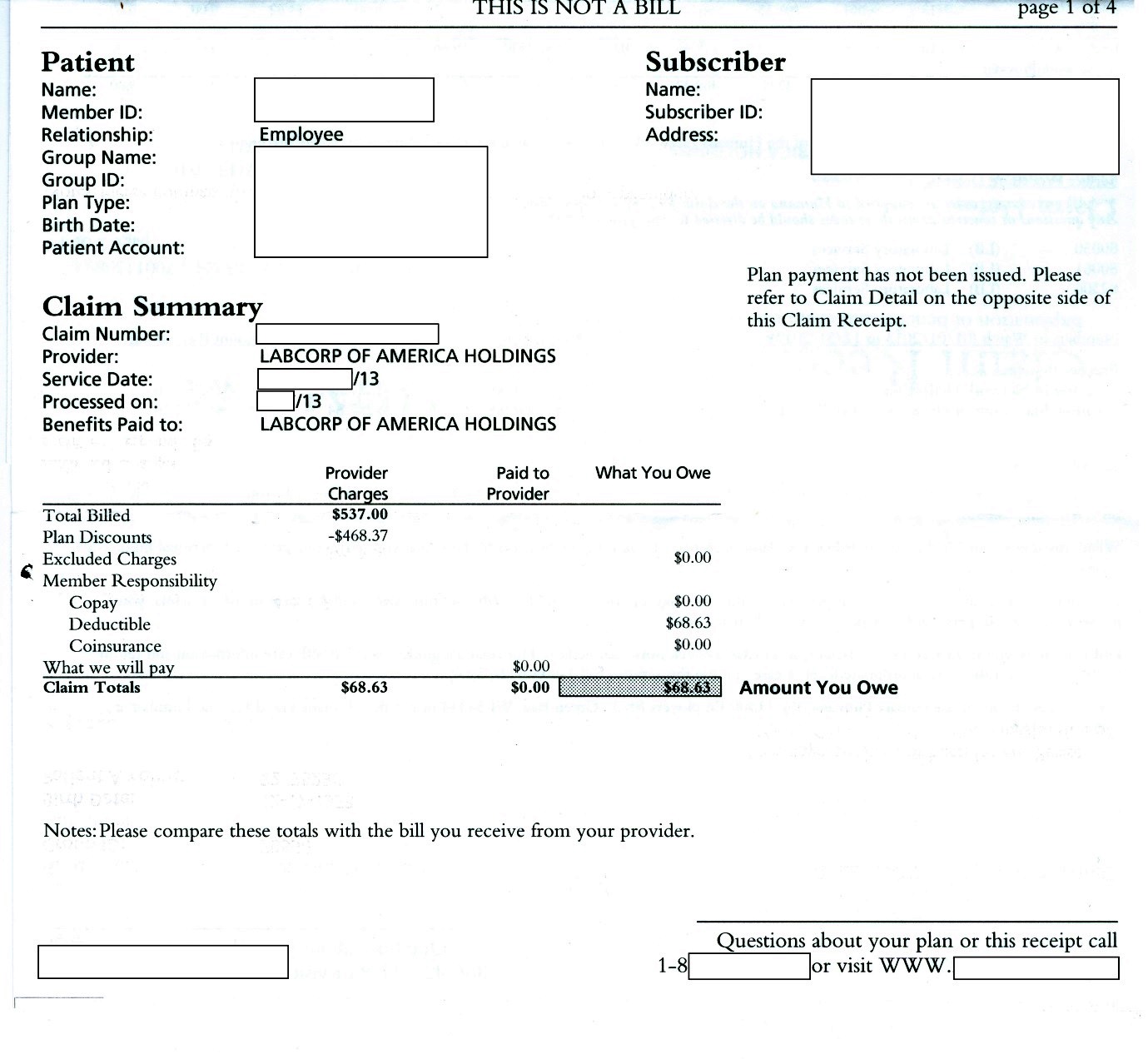

The patient needed a standard set of blood tests at LabCorp. The busy receptionist obligingly spent time querying her software to figure out the cash price for the tests. She came up with a quote of $537.00. Given the quote, the patient decided to go with his insurer’s network price.

Wise move.

As the statement of benefits shows, the network price was $68.63, a $468.37 saving over the cash price of $537.00.

This experience provides food for thought in several dimensions:

- With respect to claims by legislators that requiring providers to post their prices will help reduce medical costs, which price do you think LabCorp will post? Will this be an improvement that justifies the regulatory burden?

- Based on a variety of anecdotes (and if one has enough anecdotes they become data), smaller medical entities like individual physician practices and stand-alone therapeutic facilities are almost always willing to offer a cash discount. So are hospitals, when approached by firms in the business of arranging cash discounts. ObamaCare rules are designed to replace small health care businesses with large networks run by hospitals or insurers. What will this do to people’s ability to negotiate lower prices using cash payment?

- Medicaid managed care, which emphasizes contracts with big networks, has long been promoted as a cost reducing alternative to Medicaid fee-for-service, which pays individual physicians for their services. Accumulating evidence suggests that, contrary to expectations, Medicaid managed care ends up costing more than fee-for-service. What role does organizational size have in resisting pricing pressures?

My question is, what is the real cost to perform those tests? I’d wager it’s somewhere between the $70 and $500. Hospitals overcharge insurance companies and self-pay patients to make up for the money lost by accepting Medicaid/Medicare.

The answer to question 1 is this:

If Labcorp exists in a vacuum they will post the higher price. If they don’t exist in a vacuum they will post a price that is competitive in their local market, assuming Testcorp across the street also has to post prices. Lapcorp will price at $400, then Testcorp at $380, then Labcorp at $350. And they will compete until a fair price is reached. Meanwhile smart people in Silicone Valley will create new websites that collect and aggregate price information allowing customers to more easily find the best price. They will perhaps sell ads to Labcorp and Testcorp who will then advertise their new low prices.

Quite frankly, its a silly question, you might as well ask “Why doesn’t McDonalds charge $30 for a bigmac?”

If products and services are sold with prices on them and consumers are shown the price and make purchase decisions based on that price then the free market will eventually come to a fair price for the product. This is the same for any product or service, there is nothing special about medical services that would prevent this, and indeed it doesn’t prevent it in the realms of cosmetic procedures. The only problem is, right now, medical services aren’t sold with prices on them, consumers are never shown the price, and consumers do not make purchase decisions based on price (because they’re not the purchaser in the end, only the consumer).

Have we forgotten that the medical care industry ought to be the most service-oriented industry out there? However, it FAR from being a service-oriented industry as the service provider has a dysfunctional and non-direct relationship with the patient. If it were what it ought to be, prices would already be much lower, negotiations would be with those of lower income and more people would have more say over their own health care decisions.

It’s just so ridiculous that providers often struggle to back up any price quote they come up with because they know it is a fabricate price that is not backed up by anything other than a distorted industry.

This is such a convoluted system. No industry gives an 87% discount to good customers. Basically, the list price is fake — nobody is expected to pay for it.

We’ve seen the efficacy of large federal hospital networks, a la the VA. The really exciting part for me is that most people have no clue how much they’re paying. IA + Double Marginalization = undisclosed financial interests for legislators and certain analysts.

I’m actually curious about point 3.

This is a very enlightening insight, I am glad I read this post.

My takeaway:

Never pay list price for anything, ever!

Chris, you make a good point. The bottom line is that care providers should never be hiding prices from patients in the first place. Granted, there’s some of us that won’t hesitate to get our quotes before going into the doctor’s office. However, there’s some people that simply don’t think of these things and they are punished at the end with a ridiculous bill that makes no sense. Providers should be in favor of being transparent to their costumers, at the end of the day it’s a big reward to provide a service to someone in need knowing that they knew exactly what they were getting and they accepted it. I think.

The problem isn’t with the doctor or the lab. The problem rests in the simple fact that with a third party payor, the patient is no longer the client – the payor is. Therein lies the problem.

I find it interesing that the cash price was so much higher.

I recently had a physical, paid cash, and found out the insurance “list price” was more than twice what I paid in cash (actually a credit card).

The ACA seems to provide for not having a network of providers – giving people the ability to see whomever they choose – and actually setting boundaries on what non-network providers can charge.

I find this very encouraging.

Don Levit

In regard to one of the comments about what is the “real cost” to perform those tests… Who cares?

I don’t ask Lays potato chips how much the “real cost” of the potato chips. I make the decision based on my out of pocket in the grocery store. The out of pocket cost is how patients make their decisions. Of course, medical and health care is not as substitutable as potato chips – so the analogy is weak.

Patients (and their employers) have ALREADY done their shopping on price! They settled on a per month premium. They have paid an insurer to then get the BEST price for those services through the network. I am not foolish enough to believe that insurance financing is the same as actually buying health care, but many employers and employees (patients) do.

How do patients/employees then shop for medical and health care? They shop on convenience and reputation. Price shopping has been addressed and relegated to an afterthought by the benefit structure (which employers have PAID for and put into place).

To make customers care about spending (not cost – that is never known to a consumer), it has to be completely in their control AND they must feel the consequence of poor price decision making.