Is Medicaid-Associated Overuse of Emergency Departments Just a Temporary Surge?

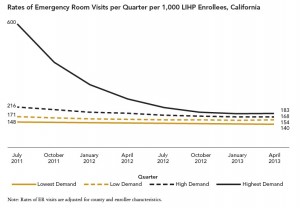

Research from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research suggests that increasing Medicaid dependency does not result in a secular increase in use of hospitals’ emergency departments (EDs). Rather, the jump in ED use is just pent-up demand being satisfied, which then drops off. This is the conclusion of a study that examined ED visits by California patients newly enrolled in a government program similar to Medicaid, called the Low Income Health Program (LIHP).

The study suggests different consequences of Medicaid expansion than the Oregon Medicaid experiment showed:

Although our results are not directly comparable to those of the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, they suggest that the higher costs and utilization among newly enrolled Medicaid beneficiaries is a temporary rather than permanent phenomenon. To the extent that California’s experience with the pre-ACA HCCI and LIHP programs is generalizable to other states, policymakers and service providers can expect a reduction in demand for high-cost services after the first year of Medicaid enrollment.

If true, this contradicts a long-running theme of this blog, and it should make us happy that the new Medicaid dependents will get timely, quality, preventive care that will reduce their need to go to EDs.

“We found that the surge doesn’t last long once people get coverage,” said Nigel Lo, a research analyst at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the study’s lead author. “Our findings suggest that early and significant investments in infrastructure and in improving the process of care delivery can effectively address the pent-up demand for health care services of previously uninsured people. Fears that these new enrollees will overuse health care services are just not true.”

Well, maybe. The new Medicaid dependents were enrolled in county-specific managed-care plans, and I’ve recently suggested that those Medicaid programs perform better than Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS). Nevertheless, the conclusion evangelized by the authors is unconvincing.

In the first three months after enrollment, there were six ED visits for every 10 new beneficiaries in the “highest-demand” group. This is the group which was previously uninsured but had not used county indigent services prior to enrolling in the government program. It comprised 37 percent of the newly insured. However, there was no barrier to them using the ED when they had been uninsured: Nine percent of the newly insured had used EDs before getting coverage. (The rest of the newly insured had been on another government program, Health Care Coverage Initiative, which was cancelled.)

What is important to remember about Medicaid and similar programs is that you can sign up when you need care. People with private insurance can only sign up during open-enrollment periods.

Sure, the people who sign up for Medicaid will consume a lot of medical care and then drop off. But they will also drop out of Medicaid until they need it again. Meanwhile, eligible people who become sick will sign up next month. It never stops.

And it certainly does not address the problem that Medicaid provides poor access to physicians. If it did, the newly covered would not have had to flood hospitals’ emergency departments.

Hi John:

Until we incentivize patients to take responsibility for their own well-being and share in savings they can generate, the inefficient use of resources will continue. To paraphrase Bill Clinton’s motto about the economy: “It’s the patient, stupid.” We must make them responsible, motivated participants in generating health care savings while improving their own health and outcomes.

Have a very Healthy and Happy Day!

Charlie Bond

Medicaid has always been associated with emergency room (ER) visits. It may be that Medicaid enrollees lack of a regular doctor; maybe they cannot get a timely appointment, or maybe a lack of planning. It may even be related to a population that is accustomed to seeking care in the ER, and doesn’t quite fathom that primary care in the ER isn’t the normal way to access care. Whatever the reason, it’s not likely to go away. All the above reasons may be involved. However, I suspect that it’s mostly due to the inability to get timely appointments.

Devon,

I think it’s all of the above. It’s all well and good to promise people access to insurance, and it may alleviate issues with catostrophic illness. However, it does not ensure access to primary care, nor does it ensure that if that access is offered, it will be taken.

“a population that is accustomed to seeking care in the ER, and doesn’t quite fathom that primary care in the ER isn’t the normal way to access care.”

Devon, I’ve recently had the opportunity to speak with hospital workers in DFW who all speak to that; race and culture in addition to subsequent information and education undoubtedly play pivotal roles.

What I see in southwestern Ohio( where Medicaid has expanded) is that the Medicaid recipients use urgent care or the ERs. Most other primary care is provided by community health centers which are understaffed (hard to find physicians because of compensation and other issues) and do not appear to be run with objective of meeting needs of population.

The physicians employed by hospital systems will see some Medicaid to protect the hospitals’ 501(c)3 status; however, only a small percentage of visits, about 5 %, are for Medicaid. The reimbursement for a typical 99213 visit is not enough to cover costs; so physicians in a private practice largely avoid Medicaid.

Thank you. Are you referring to physicians whose outpatient practices have been rolled up by hospital systems? We’d value your insight on why hospitals consistently lobby for Medicaid expansion. I’ve written about it lots at this blog. It makes no sense given your statement.

All of which raises the question as to how often do people in countries with national health insurance access their system? Is it more or less than what Americans access Medicaid? For example in Great Britain people pay “nothing out of pocket” to access care. A comparison of this nature would be “interesting” to see. I do know that Americans visit doctors “less” on a per capita basis than do people in most of the rest of the developed world.

Thank you. There are long waiting lists for doctors’ appointments in the U.K., Canada, and other countries. I refer you to The Fraser Institute’s book, Reducing Wait Times for Health Care: What Canada Can Learn from Theory and International Experience, edited by Steve Globerman, published in October 2013.

Notes to Jerome:

Doctors in those other countries do not owe thousands of dollars for their education. They can work for much less. I believe the average doctor in France makes the equivalent of $55,000 US.

As for hospitals:

Most of the hospital’s costs are covered by taxes. They do not need to worry if the reimbursements do not ‘cover their costs.’

“Doctors in those other countries do not owe thousands of dollars for their education. They can work for much less.”

Well said, Bob. You raise a very crucial point: the hyperinflation of higher education has adverse effects beyond just personal debt.

Medical school debt would have little effect on salaries unless it’s effects physician supply. What I suspect we have in the United States is a system that compensates physicians well, which boosts demand for medical education. That demand means medical schools can charge high tuition, and must pay high salaries to faculty. On the other hand, France probably restricts entry into medical school, but pays most of the tuition costs. When medical graduates begin to practice, they discover the dominant payer uses monopsony power (maybe outright price controls) to hold salaries down.