How Government Payments Inflate Medicaid Expenditure

Real health care reform would adopt reimbursement policies providing a level playing field for all providers regardless of the form of business organization (proprietorship, partnership, corporate, etc.) they choose, their profit or non-profit status, or the level of subsidy provided to them. It most definitely would not distort production outcomes and promote inefficiency by paying “reasonable costs” to favored providers while imposing lower rates on others.

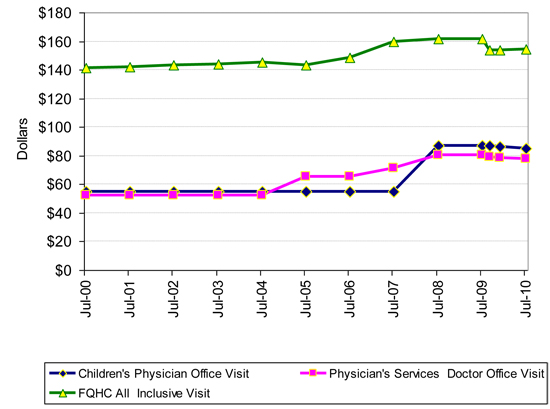

The graph below gives a glimpse of just how much Medicaid discriminates among institutions. It shows the difference in reimbursement rates for office visits to Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), private physicians, and private physicians who care for children. The original is here.

The upper green line shows Colorado Medicaid reimbursement rates for Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) visits since FY 2000-01. Colorado Medicaid encourages Medicaid recipients to use FQHCs rather than private physicians. Prior to the recession, the state also subsidized FQHCs by paying for buildings and equipment. Many FQHCs are run by hospitals that also enjoy Disproportionate Share Payments that subsidize their treatment of Medicaid patients.

FQHC rates were 35% higher than the reimbursement rate for physician office visits. Rates went from $52.64 and $141.11 for physicians and FQHCs in 2000, to $77.82 and $154.55 in 2010. Physician reimbursement increased by more than the inflation rate. FQHC reimbursement did not. The value of building and equipments grants to FQHCs are not included. Private physicians received three rate cuts during the recession, FQHCs were cut twice.

In 2008, Charles Ingoglia, the Vice President of Public Policy for the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare reported that in one state the payment for psychiatric medication service, code 90863, was $12.50 at a university medical center clinic, $39.92 at a Community Health Center, and $80.00 to $88.00 at a FQHC. In a nearby state, the reimbursements were $19.53, $210.87, and $88.82 to $155.64. The FQHC amounts vary because FQHC reimbursements are recalculated quarterly to account for changing costs. Although Mr. Ingoglia did not provide definitions, his Community Health Centers may be FQHC “look-alikes.” These types of organizations fulfill the requirements of the Section 330 Public Health Service Act but do not receive grant funding under it.

Advocates for FQHCs generally claim that payments to FQHCs should be higher because people present them with multiple health problems and receive “all inclusive” services. They do not address the fact that private physicians also see people with multiple health conditions or the fact that the covered services at a FQHC are similar to those provided by private practices. Both entities provide services and supplies “incident to” the services of physicians, many physician practices routinely include the services and supplies of non-physician “practitioners”; both train patients in self-management of their conditions; and both offer preventive primary health services.

Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF), the agency that runs Colorado Medicaid, is on record arguing that it is inappropriate to use standard inflation adjustments to judge its reimbursement rates. It believes that Medicaid reimbursement is “artificially” capped at the Medicare limit and that Medicare reimbursement does not change according to medical inflation rates. Therefore, it maintains that “it would be misleading to adjust the Medicaid rates using the consumer price index to gauge the change in costs in real dollars.”

It is difficult to believe that state officials are unaware of the fact that federal law requires Medicare rates to be routinely adjusted for inflation using both cost-of-living estimates and area wage difference estimates. Or that the “reasonable costs” of FQHCs, the basis for their reimbursement rate, are not affected by changes in the general price level.

If standard inflationary adjustment techniques cannot be used in evaluating Medicaid reimbursement rate growth, one wonders how HCPF, or any other government health agency, plans to evaluate the adequacy of the payments it sets.

The money government health agencies spend is taken from productive people who must earn the incomes that pay for Medicaid expenditures. Unlike the health systems on the government dole, they do not enjoy automatic income increases when their “reasonable costs” go up, do not get automatic cost-of-living increases, and do not enjoy wage difference area adjustments. By refusing to adjust government payments for the changes in real prices faced by the people who pay the bill, government disconnects government health payments from reality and fuels unnecessary increases in health care costs.

That is the nature of bureaucracies. Groups lobby for favors, which are often granted based on arbitrary factors. In many states, primary care is reimbursed lower (in comparison to market value) than specialties. I expect this is a rationing technique, since primary care is often the gateway to specialists.

Where’s the graph?

@Beth

Check out page 52 of the report. It shows a graph of rates by type of facility over time.

Beth and Devon: sorry for the confusion. The first post that went up omitted the graph. Problem has been fixed.

John, now I know why you had an earlier post about community health centers. That’s going to be the only place a lot of us will be able to ge care.

I think Vicki has figured this out.

Interesting post. You wonder what is the point of all this?

The point of this is to create a health care system run by government and paid for by taxpayers.