How We Ration Care

There are not very many good things you can say about a deep recession. But from a researcher’s point of view, there is one silver lining. This recession has given us a natural experiment in health economics — and the results are stunning.

But, first things first. Here is the conventional wisdom in health policy:

- In the United States, we ration health care by price, whereas other developed countries rely on waiting and other non-price rationing mechanisms.

- The U.S. method is especially unfair to low-income families, who lack the ability to pay for the care they need.

- Because of this unfairness, there is vast inequality of access to care in the U.S.

- ObamaCare will be a boon to low-income families — especially the uninsured — because it will lower price barriers to care.

As it turns out, the conventional wisdom is completely wrong. Here is the alternative vision, loyal readers have consistently found at this blog:

- The major barrier to care for low-income families is the same in the U.S. as it is throughout the developed world: the time price of care and other non-price rationing mechanisms are far more important than the money price of care.

- The U.S. system is actually more egalitarian than the systems of many other developed countries, with the uninsured in the U.S., for example, getting more preventive care than the insured in Canada.

- The burdens of non-price rationing rise as income falls, with the lowest-income families facing the longest waiting times and the largest bureaucratic obstacles to care.

- ObamaCare, by lowering the money price of care for almost everybody while doing nothing to change supply, will intensify non-price rationing and may actually make access to care more difficult for those with the least financial resources.

Interestingly, the natural experiment that forms a test for these two visions is the recession.

Only time will tell

If I am right or I am wrong

As explained in a recent report from the Center for Studying Health System Change, middle class families are responding to bad economic times by cutting back on their consumption of health care. They are postponing elective surgery, forgoing care of marginal value, and making more cost-conscious choices when they do get care. This reduction in demand is freeing up resources which are apparently being redirected to meet the needs of people who face price and non-price barriers to care. From 2007 to 2010:

- The percent of the population experiencing an unmet health care need actually fell from 7.8% to 6.5%.

- The percent of people who say they have delayed care fell from 12.1% to 10.7% over the same period.

(See the graphic here.) And this is in the middle of one of our worst recessions!

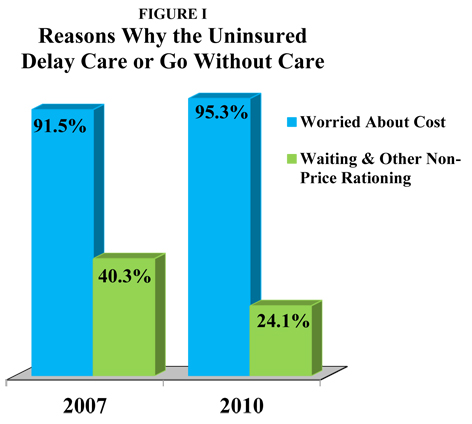

As Figure I shows, during the recession the money price barrier to care actually rose among the uninsured, although the increase was not statistically significant. The number of uninsured people reporting access problems because they were “worried about cost” rose from 91.5% to 95.3%. (Translation: virtually everybody who is uninsured worries about cost.) Yet over the same period, the number of people experiencing access problems because of waiting and other non-price barriers was almost cut in half (falling from 40.3% to 24.1%).

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

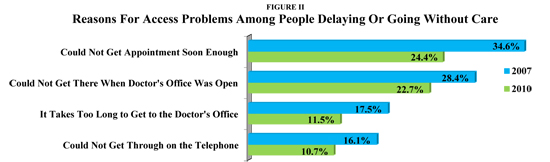

Clearly, the decrease in non-price barriers is what is responsible for the dramatic increase in access to care. Figure II shows what some of the most important of these changes were.

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

These results are consistent with an earlier study we reported on. When North Carolina Medicaid tripled both the time price of obtaining prescription drugs and the money price, researchers found that time was more important than money in deterring access to care.

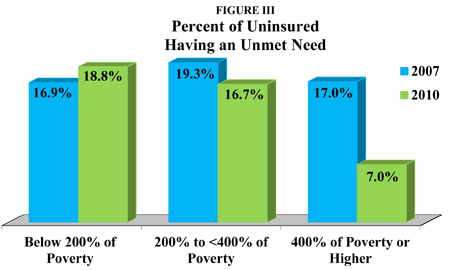

Figure III is I think the most important figure of all. Suppose that in an attempt to increase access to care, we add one more doctor, one more nurse or one more clinic. Who is likely to benefit? The figure implies that the higher your income, the greater the likelihood you will gain. During the recession, for example, the percent of people experiencing an unmet need with income at 400% of the poverty level or above was more than cut in half. Yet, among those with income below 200% of poverty, the percent of those with unmet needs actually rose.

Source: Center for Studying Health System Change

Think (metaphorically) of a waiting line for care. The lowest-income families are at the end of that line. The longer the line, the longer they will have to wait for care. If you do something to shorten the line, you will be mainly benefitting higher-income people who are at the front of the line.

Why is that? As I have explained before, many of the skills that allow people to do well in the market are the same skills that allow them to do well in non-market settings. High-income, highly educated people, for example, will find a way to get to the head of the waiting line, whether the thing being rationed is quality education, health care or any other good or service. Low-income, poorly educated individuals will generally be at the rear of those lines.

One policy implication is that we should allow low-income people on Medicaid greater access to services whose prices are determined in the marketplace. For example, let Medicaid enrollees add to Medicaid’s fee with out of pocket money and pay the market price at walk-in clinics, surgi-centers and free standing emergency care clinics. Another implication is that we should make it easier for market-based suppliers of care to reach low-income patients (e.g., by relaxing occupational licensing restrictions).

A third implication concerns ObamaCare. As we have pointed out before, about 32 million people are expected to be newly insured, and if economic studies are correct, they will try to double their consumption of medical care. The act inexplicably forces middle- and upper-middle income families to have more coverage than they would have preferred (a long list of preventive services with no deductible or copayment); and once they have it they will use it. Yet in the light of this rather large increase in demand, nothing in the act really increases supply. (I suspect this was to induce the bean counters at CBO to low-ball their estimate of the cost of the bill — if there are no new doctors, CBO is likely to assume there will be no additional care, regardless of what was promised.)

What we can expect is a rather large increase in non-price rationing — as waiting lines grow at the family doctor’s office, the emergency room and everywhere else. In such an environment it is inevitable that those people in a health plan that pays fees below the market price will be pushed to the end of the waiting lines. These include the elderly and the disabled on Medicare, low-income families on Medicaid and (if Massachusetts is a guide) people with subsidized insurance in the newly created health insurance exchanges.

Ironically, ObamaCare may end up hurting the very people many ObamaCare supporters thought they were going to help.

One result of creating a third-party payment system that is (theoretically) supposed to pool risk and pay for medical is the huge bureaucracy. It’s no wonder why the inconvenience of scheduling an appointment and driving to the doctor’s office is a bigger barrier than cost. We still pay the cost, but it’s indirect so consumers cannot adjust their consumption and providers are not free to rebundle and repackage services and expect to be paid.

It’s difficult to even imagine what medical services would look like in a world where everyone paid cash at the time of service and medical licensure and prohibitions on the corporate practice of medicine were absent.

Non-price rationing should be central to the dailogue on healthcare reform. Consumers tend to view rationing in ways that can be measured monetarily.

I’m a bit confused. Figure III shows that the poorest uninsured (under 200% of the poverty level) had an increase in unmet need over a time when overall demand for care fell. Why does that lead to the conclusion that an increase in overall demand for care would lead to a more drastic increase in unmet need for the among the same group?

Very, very interesting. Good post.

I agree that this post is interesting. Even exciting. It points to the fact that everything we are doing to help the uninsured is wrong.

Great insight.

I agree with you 100% and have noted a similar pattern with those whose insurance changes. The best insurance goes to the front of the line. The worst insurance goes to the back of the line. Those with certain skills who previously had good insurance that went bad could move themselves back to where they were before.

Carolyn says “Non-price rationing should be central to the dailogue on healthcare reform”

Say that in capital letters. As the debate about dumping Obamacare (and not replacing it with something similar with a different name), the public must become aware of the economics involved in delivering healthcare. It doesn’t take someone as smart as John Goodman to come to the obvious conclusions (if common sense is not eliminated in the process of getting a chicken in everyone’s healthcare pot).

Price controls lead to rationing and the monetary price reduction must be paid in time price regardless of what services are in question. Therefore we have to either accept the inevitability of one of the two (either higher prices or longer waits), or we take a serious look at options not involving any type of price controls.

As soon as the public comes to the realization that there is no “healthcare fairy” the sooner we can create a workable and fair system.

Very good post. Very interesting.

Unfortunately, the public has such an entitlement mentality with regard to health care that it will be a tough sell. The public sentiment is that seniors should get mostly free health care, poor people should get mostly free health care and employed people should get mostly free health care. But as Frank pointed out, there is no Healthcare fairy so the money has to come from somewhere!

No where is the proof of rationing by waiting more apparent than in the public hospital. Even once the patient sees a provider they then face another bureaucratic morass to get medications, procedures, or follow up care. Many end up going without, giving up in the frustration of waiting in another line. (As an aside, this correlates with the notion that lower income folks with less education ((read: less innate problem solving skills)) will give in to their frustrations and leave the line.)

If Obamacare comes to implementation and more seek care due to the lowering of a cost barrier, they as well as others will find that the waiting times will only be longer as there are not more doctors, hospitals, nurses, etc. in the pipeline.

As John has long advocated, opening up competition to allow providers to shape, repackage and reprice their goods and services is more likely to provide more healthcare to more people.

I believe the first thing that we should try in our efforts to increase access, and I think that health researchers on left and right can agree on this, is to get the states to make easier to become an MD, a PA, an NP, an RN or an LPN. It should also be made as easy as is reasonably possible to start a medical business like a hospital or clinic.

Floccina: At the same time you are advocating reducing physician and nursing training others are complaining that there are too many medical errors being made as it is. Do you think less training will improve quality? During all of this the NYTimes just wrote an article discussing that perhaps physicians ought to get advanced training in business administration. Let us not forget all the other hours that physicians are being forced to spend on recertification and political issues such as HIV, medical errors, domestic violence, end of life issues, etc. and whatever else politicians and interest groups think up in different states. I think the public has to figure out what they want from physicians. A doctor or a handyman.

Why not give Medicaid patients money (a medical account debit card) for 1st dollar care (the deductible), while the state insures (and/or re-insures) the major med insurance (HDHP). Works in the private sector. Why not in the public sector? Bob

Al & Floccina,

There is no doubt that professional education needs a revamp to make it more relevant and in many cases shorter. On the physician side, there needs to be the freedom to innovate/alter the content and pathway length to MD as long as the outcome (passing appropriate and relevant tests) is preserved.

Unfortunately, the ACGME, essentially a branch of CMS, controls graduate medical education. They will need to allow residencies flexibility in training lengths as well as content. At this time, those aspects are rigidly controlled. Allowing innovation as long as quality outcomes are preserved (or perhaps even improved!) is not currently on their radar. Heck, there just might even be some ways to save Medicare some money somewhere in her.

@Bob

You may be on the right track in that the Medicaid patient gets to make decisions on where he goes and who he chooses as a medical provider. But perhaps a voucher system along those lines may be the funding vehicle for what is now Medicaid and a tax credit for those of us who pay taxes. The “state” would not then have to be in the business of insurance.

I would imagine that the number of people that could not get an appointment soon enough (34.6 percent as seen in the chart) will go up in five years since more practices will close down. Or at least that’s what I’ve heard.

To Frank Timmins: Vouchers are for insurance policies ala Massachusetts. A debit card by-passes an expensive bureaucracy. And the state can re-insure itself with indeminity companies. It is a ‘single payer’ HRA using an HSA-like deductible (which cold be varied). This is something a good broker can set up for any private firm–wy not for the public sector? With cash in hand there is not only a savings from eliminating a bureaucracy, but the Medicaid family would also be in the private market for care enjoying the same equity in the market place as others as well as prudent use, if the medical account rolls over to the family like an HSA. Thanks, Bob

@Bob

I appreciate your point. However, I don’t see how we would have less bureaucracy with a government furnishing and managing debit cards to Medicaid recipients. Without a specific funding level (voucher) we are merely rearranging the chairs on the Titanic. The use of a voucher would give the recipient the option of buying the insurance he chooses (including HSA programs), and that recipient (like any other consumer) would become part of the free market. The government would only regulate the conditions of distributing the voucher.

Why should “the state” be the insurance source (using reinsurance or not)? Carriers competing for the coverage would be far more cost effective.

@AI

Do you think less training will improve quality?

The empirical evidence is that less trained PAs, NPs and midwives do aas well as MDs.

The theory is that school selects for people who are good at school which is different than practicing medicine, it requires different skills and attitudes. Perhaps most of the best would be doctors cannot get into medical school because they are not good enough at school. Though ability at school correlates with ability in other areas I am convinced that the correlation is not strong enough that licensing brings a net benefit because it limits the pool of people that can be selected from.

Further if there are not enough Doctors it means some might have to go without a doctors care.

If there are too few doctors some might be tired and overworked which can also contribute to errors.

Floccina: “The empirical evidence is that less trained PAs, NPs and midwives do aas well as MDs.”

On simple things my grandmother could do as well as any doctor so I guess there is a bit of truth in what you have to say, but then maybe we ought to simply replace NP’s with grandmothers. I don’t think that is quite what you mean, but that is where your logic takes us.

for Frank Timmins: Good points but a debit card is run by a (contracted) TPA with a computer–the expensive insurance bureaycracy is eliminated. in addition, the State is a “single payer” as regards Medicaid. They could run the indemnity part of the insurance, but my guess is that it would far chewaper to re-insure with real insurance companies. Again, vouchers are not money; a debit card is. With a medical account the prudent will save and roll over the money to themselves. With an insurance policy with full coverage (this population by definition has no money,a voucher would only be good for an HMO total “coverage”)–the Mass. experiment again shows that full coverage with managed care is the most expensive thing ever devised for the medical system. Bob

@ Bob

Again, I think your suggestion has merit (certainly an improvement over what we now have, but what you describe as the voucher system is not what I have in mind.

The voucher does not have to mandate that the money be spent on an HMO. It would simply define “acceptable coverage” which could include anything from high deductible programs with HSAs to total coverage programs (as you describe HMOs). Those who choose to manage their healthcare would opt for the HSA while those who want the HMO could opt for that (and something in between).

I believe you are correct that “full coverage with managed care” is ineffective and costly, but that would only become clear if proven in the marketplace. It would no longer be the problem of the taxpayer (vouchers are for a specific amount of money). Those who wish to trade time cost (limited access) for front end benefits (with an HMO) can make that decision. Others will opt for the freedom to choose and manage some possible out of pocket costs in the process.

AI

2 more things:

1. It is mostly system that reduce errors rather that the differences in doctors ability.

2. Making it easier to become a practitioner is does not necessarily mean less trained people doing all procedures. There could be more division of labor.

One group that this would effect right away would be doctors from other countries now living in the USA who cannot get licensed here.

http://www.overcomingbias.com/?s=midwives

Floccina:

1) I won’t disagree that medical error is overblown and inappropriately used.

2) My comments just tried to put your statement into a proper perspective. I wouldn’t use any doctor for standard care that wasn’t able to be licensed in the US. That doesn’t mean that all those that are licensed are the best, rather that in my opinion there is some selection involved that is good for my health. I prefer the best trained physicians that seem to practice the best medicine for my own care. As far as anyone else goes they can choose the quality they desire.

Re overcoming bias: You might believe that bias is the big problem. I don’t. In fact I have no problem with midwives. I think my grandmother’s mother brought a lot of kids into the world and I don’t know that she could read.