Explaining The Fall (And Possible Rebirth) Of Doctors’ House Calls

(A version of this Health Alert was published by Forbes.)

(A version of this Health Alert was published by Forbes.)

“Connected care” refers to a large and growing portfolio of digital tools, from video consultations with psychiatrists to in-home sensors passively detecting when a senior falls to devices that measure diabetics’ blood glucose and send messages to their families’ or doctors’ smartphones when intervention might be needed.

One very valuable service is telehealth, whereby physicians use email, phone, text, or video for consultations, reducing the need for time-consuming in-office visits. The benefit of this is illustrated by the story of Felipe Perez, a patient of the Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego County, who used to have to take a five-hour long bus and trolley trip to get to his appointments.

However, we should not fall into the trap of all-or-nothing thinking, expecting patients only to see their doctors either in the office or remotely. With a little creativity, we can envision mobile health technology leading to the restoration of an almost forgotten medical tradition: The house call. Imagine the connected doctor travelling to patients as needed, with a portfolio of cloud-enabled diagnostic, therapeutic, and decision-support tools at her disposal.

House calls used to make up 40 percent of U.S. doctors’ visits in the 1940s, before going into decline in the 1960s. These days, they comprise less than one percent of consultations. Many believe that more house calls would increase quality of care at low cost, which led Medicare to launch an “Independence at Home” demonstration project for seniors with multiple chronic conditions in 15 states. Starting in 2012, the project has had promising results.

This invites the question: Why did house calls decline? In a recent tweet, Jay Parkinson, MD, founder of the extremely innovative Sherpaa medical service claimed: “There’s a reason why house calls went out of fashion. Grossly inefficient use of very expensive doctor time + extremely limited capability.”

Dr. Parkinson’s identifying house calls as an inefficient use of doctors’ time is a very limited view of costs in health care. The almost complete elimination of house calls has not increased efficiency, it has only transferred the cost of travelling and waiting from doctors to patients.

Keith Wagstaff of ABC News covered this very well in his discussion of a study estimating the average American lost $43 in wasted time waiting for a scheduled appointment – more than the amount of the out-of-pocket payment! Further, the time spent actually consulting the doctor has shrunk to maybe 15 minutes. So, from a patient’s perspective, the ratio of productive time to wasted time has declined.

Although Dr. Parkinson insists that we also wait in barbershops and lawyers’ offices, I beg to differ. Like most men, I drop in for a haircut, and can therefore ensure I wait at the least expensive time for me. My wife, who makes appointments, would never tolerate waiting as long for her hairdresser as for her doctor. Nor do lawyers keep clients with scheduled appointments waiting for an hour or more to read old magazines in a “waiting room.” (In other sectors of society, they are called “reception areas.”)

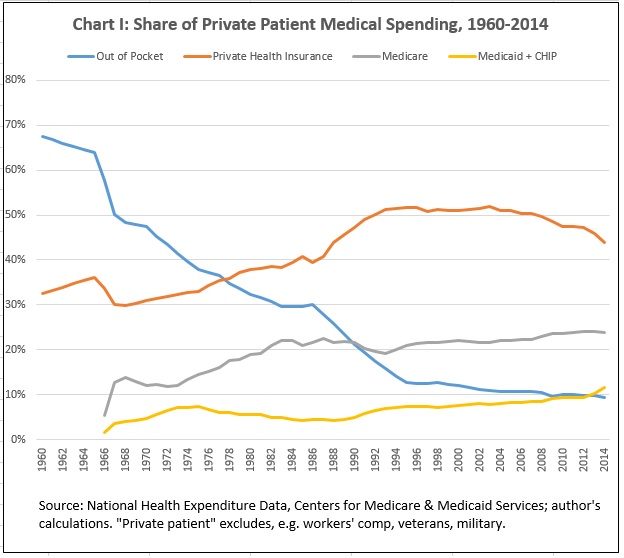

The most significant factor explaining the shift in costs from doctors to patients is patients’ having lost control of paying doctors. According to the National Health Expenditure Accounts, private patients (not those enrolled in programs like the military, veterans’ benefits, or workers’ compensation) paid 67 percent of the aggregate bill for consultations in 1960. By 2014, that had collapsed to 11 percent. Private insurance increased to half of spending on physicians in 1992 and has stayed around that share since. By 2014, Medicare paid 27 percent, and Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program 13 percent [Chart I].

As patients’ lost control of payment, they lost the ability to signal how much they valued their time, and house calls declined. Remarkably, this was over a period when people’s time became more valuable as our incomes increased, and our tolerance for queuing and visiting different vendors shrank. This is one reason for the rise of department stores, supermarkets, and (later) big box stores.

Remarkably, Dr. Parkinson’s own business, Sherpaa, is a solution to this problem:

We’re doctors and insurance guides, empowered by our first-of-its-kind secure communication and care coordination platform, who diagnose, treat and partner with your employees to get them better fast.”

Sherpaa uses innovations such as mobile technology to deliver faster, better care to clients’ employees. Those clients don not care about the doctors’ time. They care about their employees’ time.

As long as we allow the system, instead of patients, to control spending on doctors, house calls and connected care of all types will struggle to maximize their value.

So you think someone should spend 4 years in college, 4 years in medical school 4+ years of residency, so they can spend their time . . . driving – a skill that pays minimum wage at a pizza parlor? That’s how you want to use that scarce resource?

Suppose you have 8 hours of appointments in 15 minutes blocks. That’s 32 patient encounters. If you spend 15 minutes driving from house to house, you see half as many.

If you want to doctors (or their “physician extenders”) to spend more time driving and less time doing patient contact how do you expect to address shortages and wait times?

Speed, quality, price. Pick any two.

Please don’t tell me telemedicine will fix everything. When I asked you how to do a neurological exam by telemedicine you cited an article that said nothing about it. Maybe telemedicine will reach that point some day, but first you have to (1) show the profession that it provides a comparable level of care as an office visit and (2) pay for it.

We’re dealing with real people with real problems, not cells in a spreadsheet. If telemedicine is sub-par real people suffer real complications.

Do you want evidence-based care or should we just rush willy-nilly into every new idea that sounds good? That’s how the government operates.

Do the research and then get back to us. Little niches of positive findings such as remote monitoring for heart failure to prevent readmission can’t be extrapolated to medical care in general, a as the WSJ recently pointed out, hospitals are gaming their readmission stats.

I don’t recall writing that “telemedicine will fix everything” so my argument must have been better than I had thought!

I am not a fan of extrapolating any evidence to “medical care in general.” It is our search for a general theory of health care that is the cause of much of our problems.

But do your point: Nowhere do you show any respect for patients’ time. If patients paid directly, they would pay more for the convenience of an in-home visit. Because that is not possible in the so-called “system” it does not happen.

When you “respect the patient’s time” with house calls you simultaneously deny medical care to someone else. How about some “respect” for the second patient?

If I can see two patients in 30 minutes at the office but instead spend 15 minutes driving and 15 minutes making a house call, someone else is deprived of that 15 minutes of medical care. You have decreased my availability to patients by 50%. Are wait times for appointments not long enough for you?

I didn’t know that all of my comments had to be politically correct and “show respect” for anything. Can I offer you a “safe space”?

“Do the research and then get back to us.”

Doctor G, I have asked for years why more physicians don’t “do the research” and then explain to the rest of us what you believe will work best. The link you provided the other day to the Docs4PatientCare Foundation is very encouraging – strategic thinking like that from physicians needs a much higher public profile.

Isn’t the fundamental question: how to optimize and / or re-organize and / or modernize the delivery of medical care? Business and government types tell us how to do that all the time. But their plans haven’t been so good; the public hasn’t liked them; and the docs haven’t liked them, either. I think we should be hearing more from physicians. Yes physicians are much busier than business and government types, doing much more significant things. But isn’t the future of the profession important enough not to trust it to those business and government types? Isn’t it worth fighting for?

Or, if I’m wrong and physicians are generally satisfied that medical care delivery is optimally-organized today, it seems to me the best strategy for physicians would be to offer a consistent explanation for the public – and especially for politicians – rather than playing whack-a-mole as ideas arise one by one?

You may disagree, but I don’t believe I’m wrong about this. And I wish there were much more physician leadership in health policy.

John,

The big problem is that the so-called physician’s groups AMA,AAFP,ACP have fallen in step with what the government proposes. Then, when things seem to be jammed up, they start back-tracking to “protect” the docs. Meanwhile, those docs in the trenches are so busy performing the dog and pony show required of them, they have no time to invest in protestation.

THe ones who will make the changes necessary to keep patients happy and healthy will be the ones getting out of traditional insurance and Medicare and doing DPC or private pay only.

See Joe’s comment below.

Perry I understand. But the so-called physician groups like AMA etc. bear the same relationship to most physicians as union leadership bears to the average working Union member.

So I’ m really much less interested in what AMA etc have to say. I’m much more interested in what physicians have to say,

And I’ll say again to physicians, isn’t the future of your profession important enough not to trust it to business and government types? Isn’t it worth fighting for? My opinion: if docs don’t think the answers are “yes” then I fear we’re all screwed.

I think there are several types of docs.

The ones closest to retiring or quitting will do so or go into a non-clinical position. The ones who are midway in their careers will likely join a large institution and be unhappy but employed and not have to worry about the day-to-day hassles.

Some of those will go concierge or Direct Pay.

The youngest, newest have been somewhat brainwashed that the government knows best and when they get out into practice they will see how wrong they were. But then, it may be too late.

The government is more than happy to take suggestions from Ivory Tower docs who no longer practice in the trenches and leave the rest of us to deal with the fallout.

I spent the first 8 years of my career on the faculty at Duke. Here’s an alternative version:

“The government is more than happy to take suggestions from Ivory Tower docs who NEVER PRACTICED in the trenches and leave the rest of us to deal with the fallout.”

I also note that Mike Roizen, who was a true pioneer in cutting costs by eliminating excessive preop testing, seems to not eat his own cooking. Every once in a while John Mauldin will write about his annual physical at the Cleveland Clinic with Roizen that seems to involve “a day of tests”. Either Mr. Mauldin is very ill or someone is being over-tested on a routine physical.

I don’t disagree at all. I just want to know how you (or anyone else) propose to study these things and where the money will come from.

Asking business and government to solve these problems is like asking your heroin dealer about a good detox facility. Unfortunately that is where the money and power are.

I think D4PC is on the right track and I know some of the people involved. They are really passionate but they don’t seem to be able to get any traction.

When people think of medical leadership they think of the AMA. However, less than one doctor in 5 is a member. Doctors hate the AMA.

IMHO the AMA is just a front for the CPT/ICD coding book business. That is a government-granted monopoly worths millions of dollars and they are not going to jeopardize that. The physician leaders come and go, but there is an army of suits that stay on forever. They control the AMA.

I still don’t see how I doctors valuable time is paid for/reimbursed while he or she is waiting in a traffic jam to go to a patient’s house? I could understand it if it were a concierge practice where patients pay a hefty premium to use the doctors time but outside of that it doesn’t seem like a an economically feasible business model.

Exactly. It has nothing to do with “respect for the patient’s time” and everything to do with the most efficient way to provide a scarce service.

Michael Jackson paid a lot of money to monopolize one doctor’s time. If Dr. Murray had been a truly great doctor then Michael Jackson would have deprived a lot of people of benefiting from the man’s talents.

Ironically, it was probably a public service to decrease the public’s exposure to Dr. Murray but that was not the intent.

We at the NCPA used to write about how physicians are the last profession to embrace the telephone. Accountants, lawyers all communicate with clients on the phone. Then I read about a history of the telephone. Doctors where among the first to have telephones installed so they could talk to the pharmacies. They apparently would also use the phone to talk to patients until insurance began to pay for most doctor visits — but not phone calls.

I used to speak with patients over the phone for routine problems. There comes a point where you can’t afford to give away any more of your time, and that time approaches faster when your fees aren’t keeping up with inflation. AS dozen 5 minute calls is an hour of free service.

For the most part I handle non-emergent phone messages through my nurse so I’m still providing free services until she agrees to work for free. If she brings me a message that’s concerning I might call the patient or have them come in.

Yesterday I had a patient whose spine MRI showed an incidental finding of a new aortic aneurysm above the level of his previous stent.

I called the patient to notify him and to get the name of his surgeon. Charge to patient: zero.

Then I placed a call to the surgeon who did his stent and discussed what we had found. Charge to patient: zero.

What would an attorney’s bill look like for that?

My point is that you would be more willing to provide a dozen 5-minute phone calls if each call paid you, say, $25. Obviously, some calls are worth more than that, while some may be worth less. I’m not advocating doctors give away calls for free. A lawyer typically charges by the incremental time. The reason why you are reluctant to give away an hour of your time is because patients and insurers are reluctant to cough up money for a phone call, but assume it’s normal to pay much more than that for an office visit. If more of your patients had telephone visits that they paid cash for, you might even be able to have a smaller office waiting area with a smaller billing staff.

“What would an attorney’s bill look like for that?”

Michael,

I suspect that if the lawyer worked for a large corporate law firm, he or she would bill for between 0.10 and 0.25 hour for each of those calls. On the other hand, the solo practitioner that I worked with for years to handle matters like wills, POA, house closing, etc. told me once that he worked about 10 hours for every six that he billed and his hourly billing rate was very reasonable. Obviously, he wasn’t getting rich.

One time, he spoke to me for 15-20 minutes about an estate planning matter and at the end of the conversation, I specifically asked him to send me a bill. He refused to do so.

Barry,

Billing 6 hours for every 10 worked was a conscious decision. It wasn’t expected of him or forced upon him by legislation.

In the end, though, shouldn’t the provider of a service decide whether or not to leave money on the table?

My husband, who has a busy estate planning practice, does not charge for 5 minutes calls, otherwise every contact (phone, email or appointment) is charged in 6 minute increments. In his law practice, we do not charge clients for their appointment if they have had to wait more than 10 minutes. Also, the maximum billable day seems to be five or six hours for every eight worked. So many mundane thing like research, personnel,office issues are not billable to a particular client and are absorbed as overhead.

I cannot understand how doctors let themselves be abused by insurers and Medicare/caid so that it seems to be unprofitable to help patients. This government obsession with coding every procedure seem very foolish and a much bigger wast of time for both provider and patient. Eventually, the bureaucrats will realize this but they will have ruined a very good health system.

Last year there was a study that reported doctors spend 1/6 of their time just on paperwork. That’s just paperwork, not the overhead you describe for running an office.

How did doctors end up like this? Not enough money to purchase the necessary laws and regulations. Or maybe just outbid. At one time the AMA was a strong lobby but they strayed off course and doctors felt it no longer represented them. What’s left are some activist state medical societies.

If the client is paying the bill directly, of course the provider should be able to decide whether or not to leave money on the table. If an insurer or the government is paying, I think both have a right to decide what they will pay for and under what circumstances and, through negotiation with the provider, how much they will pay.

I know individual and small group practices have little or no negotiating leverage with either insurers of the government (Medicare and Medicaid). They can decide to not contract with them if the payment and documentation terms are too onerous but I know that it’s often easier said than done, especially in the case of Medicare.

The other day my wife called a compound pharmacy for a 90-day refill, which comes with a significant discount over the 30-day. The pharmacy told her she only had a 30-day refill left on her prescription. They called her doctor, who refused to renew an extra 60 days until she came in for an office visit (because they had last seen her 6 months ago). My wife took off work, drove 15 miles to her doctor’s office and talked to a PA. My wife pulled out a sample blood test results page to see if that blood test panel was adequate for the doctor’s office. It was so my wife called the testing service and made an appointment at Labcorp. On the way home she swung by the pharmacy.

My point: My wife is a consultant. Her opportunity cost was an order of magnitude more than $43. Between talking to the lab, talking to the pharmacy, calling the doctor and visiting the doctor, visiting the lab, she will have spent more than three hours of her time. I imagine she would rather have an agreement with her doctor to get a blood test twice a year, have the results sent to the doctor, who reviews it calls her if necessary, sends her a bill and renews her prescription. But that’s not the system we have.

Well some of this seems self-inflicted. The opportunity cost was due in part to your wife’s desire to spend less money on her medication. Did she end up net positive by going through all this or should she have just paid for a 30 day supply and made an appointment later that was less intrusive? Did she “lose” $500 in opportunity in order to save $1500 on medication? A 90-day supply is not an emergency.

How do you think the doctor’s office should have handled it?

Without knowing your wife’s medical condition, the medication, and the cost I can’t say how I would have handled it but I’m curious as to how you think they should have responded.

As an aside, I’m extremely curious about the compounded medication, which is often an extremely expensive scam. Since it was compounded I can see where that could get expensive. I’ve seen patients bring in bills for $2,000 for a one month supply of useless garbage that costs $5 to make.

The compounded pain cream business is predatory and disgusting, and the bioequivalent hormones are not far behind.

“I’ve seen patients bring in bills for $2,000 for a one month supply of useless garbage that costs $5 to make.

The compounded pain cream business is predatory and disgusting, and the bioequivalent hormones are not far behind.”

Michael,

I would be interested in your professional opinion of Valeant Pharmaceuticals if you have one and would care to offer it. Expensive skin medications are a significant part of their business and they’ve raised prices very aggressively in recent years.

What they do isn’t unique at all. My colleagues and I have watched with wonder as drug shortages emerged repeatedly over the years. At one point there was a shortage of a common IV solution, 0.9% saline. Yes, we had a shortage of saltwater!

IMHO the media and Congress are focusing on the wrong people. They need to look at how the FDA and PBMs manage to thwart normal market mechanisms. If the price of something goes up dramatically isn’t that supposed to draw competitors into the game? Aren’t people supposed to seek out less expensive alternatives? What blocked those behaviors?

The FDA creates a “moat” around these products, as does the Patent Office. Valeant’s Acanya is a patented product that combines two common acne medications: clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide. Clindamycin is off patent and benzoyl peroxide is OTC. Put them together and you have a patentable compound.

If someone puts these together in one tube and creates a convenient way to apply the two meds together the market might attach a small premium to it but not several hundred percent.

Ordinarily people would seek cheaper alternatives but with medications that requires a sophisticated level knowledge. Most people know how to find cheaper socks but where do you find cheaper clindamycin?

You set the hook with free samples or discount cards. You seed the doctor’s office with your patented drug, the doctor gives it to the patient, and if it works the patient asks for refills.

There’s no shortage of examples. The makers of tramadol did something similar when it went off patent. They came up with Ultracet, a combo of tramadol and acetaminophen. I have new patients who ask me to refill their Ultracet and I always refuse. I give them a script for generic tramadol and them to use their savings on a year’s supply of generic Tylenol.

Through extortionate spread pricing PBMs jack up the cost along the entire chain from manufacturer to pharmacy. Again, nothing new. I first read about this 10 years ago.

PBMs also steer patients to their own pharmacies where they pay higher prices. I literally had to fight with an insurer in order to get them to use a cheaper source (me). The patient wanted a Synvisc injection. I get it for a bit over half the retail pharmacy price so we already know the markup at a pharmacy is at least 100%. My markup is about 10%.

The insurer insisted on using their pharmacy. The designated pharmacy wanted even more than I’ve usually seen retail. The cost difference to the patient was about $600.

The patient couldn’t swing it given his crappy deductibles and co-pays. My staff spent 45 minutes fighting to get the insurer to use the cheaper source. Why would they be so resistant to using a vendor at half price?

It sounds like a totally screwed up system to me.

Another thought or two. This was a transaction involving your wife and the pharmacy (and perhaps an insurance company or do they refuse to pay for compounded meds?).

The interaction resulted in a financial dilemma for your wife.

Somehow this doctor, who is not party to this transaction at all and has no idea what’s going on, is the bad guy?

How does someone who routinely gets 90-day refills end up with just a 30-day refill? This scenario doesn’t make sense.

Was this a last-minute refill of an important medication? Down to the very last dose and it couldn’t wait? Many medications can be interrupted without consequence. If you forget your cholesterol medication, baby aspirin or hormone replacement for a few days you won’t suffer significant harm. We routinely hold blood thinners for as long as a week before certain procedures. I’m having trouble thinking of a compounded medication that requires immediate attention.

Where was the urgency? Did the doctor’s office open up a slot for your wife right away so she could save money on her prescription? That was rather nice of them.