Does It Pay to Work?

This is Gene Steuerle before a House Ways and means subcommittee, via Chris Jacobs:

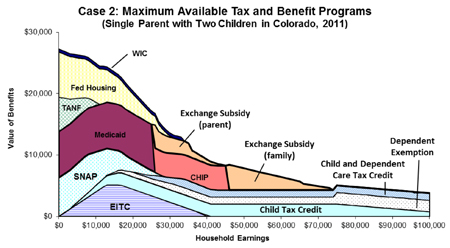

The chart below shows a hypothetical example whereby a family (single parent and two children) can receive nearly $30,000 in government benefits with no household earnings, but only about $10,000 in government benefits with $35,000 in household earnings:

Another chart shows a similar example from a slightly different graphical perspective. The chart (Figure 4) shows the effects of rising income on a single parent with two children in Alabama whose income rises from the federal poverty level to twice poverty. Under that situation, if the family’s income rises by about $17,000, the family will LOSE over $10,000 in government benefits. As a result, “income would rise by only about $6,900 — an effective average marginal tax rate of about 60 percent, to which must be added any loss of health insurance benefits.”

This, like most of our welfare programs, serves mainly to keep people where they are economically, and to remove the incentive to increase household revenue.

This phenomena may be more prevalent in Europe.

Answer to your question: No.

In economic terms, public assistance that phases out as income rises creates the equivalent of a high marginal tax rate. Of course, high marginal tax rates discourage additional effort. In this case, additional effort refers to getting a job that gets families off public assistance. Another way to look at this is: these phase-outs reduce the cost of leisure time.

People always have to weigh the cost of leisure. For instance, a doctor often has (fixed) office overhead that consumes virtually all of his or her income for the first 50% to 75% of hours worked. Yet, the marginal hours worked after the first 40 hours per week might represent a profit margin of 75% of each dollar earned. Thus, a doctor working 60 hours per week might earn double the weekly income of working only 40 hour weeks.

The point: by working 20 hours more per week, a physician is deciding the cost of 20 hours of additional leisure comes at too high a cost. But, a person on public assistance might look at their wages per hour and subtract the benefits lost (per hour of work due to income-based benefits phased out) and decide the cost of leisure is low by forgoing work. To put this another way, if people realize they can only increase their income by, say, 20% in return for taking a full time job, they will probably decide the loss of income is a small price to pay for all the added leisure time.