Why You Should Care About Actuarial Value

In order to standardize health insurance plans, the ObamaCare law requires insurers to offer plans that are categorized as Bronze, Silver, Gold and Platinum. These plans, in turn, must cover 60%, 70%, 80% and 90%, respectively, of the expected costs. The “actuarial value” of a claim is the average amount a plan with a given set of benefits is likely to pay given a standard population.

If the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) overestimates actuarial value, which it appears that it has done, the bloated insurance plans required by ObamaCare can be offered with higher deductibles, copayments, and other out-of-pocket costs than would otherwise be the case. All else equal, higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs also enable lower premiums.

Lower premiums improve the political palatability of the exchange plans. Because higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs are relatively more attractive to the healthy than to the chronically ill, they are attractive to insurers seeking to improve the risk profile of the group of people signing up for their plans.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPJgep65GMA

I saw the light

There is no standard for defining a standard population or for determining its health expenditures. Insurers have historically combined experience and actuarial judgment to arrive at their spending estimates. In 2011, The Kaiser Foundation conducted an experiment in which it asked three highly respected actuarial firms to estimate ObamaCare’s allowable Silver plan deductibles under a common set of assumptions. The standard populations differed, and the estimates of allowable deductibles ranged from $1,850 to $4,200.

People who purchase health insurance with their own money balance the extra cost of having an insurer cover smaller costs like routine screening against the higher premiums it will charge to do so. In 2009, almost half of all individual policies purchased for a single person had deductibles that were higher than $2,500. Some of the more popular pre-ObamaCare individual policies featured deductibles of $5,000 with no additional cost sharing after the deductible. People who chose those policies knew their annual financial risk in advance.

ObamaCare makes those policies illegal. It generally limits deductibles to $2,000 per individual and $4,000 per family in the unsubsidized individual and small group markets, even though total cost sharing can be as high as $6,250.

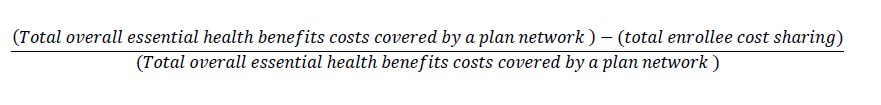

In its estimates, HHS defines actuarial value as

Proprietary data from Milliman suggest that the average annual per individual claims cost for a commercially insured population in 2010 was $4,000. Assuming that the deductibles were the entire amount of cost sharing, and a market average deductible of $2,500, the commercial insurance market’s HHS actuarial value would have been about 0.38. In order to qualify under ObamaCare, deductibles would have had to fall to $1,600, likely triggering an increase in premiums.

When the actuarial value calculations were carried out, the amount of cost sharing that ObamaCare allowed depended upon the government’s estimate of the overall plan costs for plans that have not yet taken effect. In a methodology report, HHS explained how it estimated plan costs for its standard population. With one exception, the choices made would likely overstate the cost of essential benefits coverage.

The HHS estimates are based on claims by 12.6 million people. They were culled from 2010 claims data for 39 million people provided by Blue Health Intelligence, a spin-off of the BlueCross and BlueShield Association. HHS discarded claims from individual policies, claims from groups that were not covered by PPO/POS plans, claims from groups without maternity claims, claims from groups of fewer than 50 people, and claims from groups that didn’t have at least one claim over $5,000. The report does not provide basic sample characterizations and is silent on a number of issues that are known to affect claims, things like age, geographic distribution, and the prevalence of union plans.

Plan design matters because plan design affects the claims that people make and the claims that plans pay. For example, the RAND Corporation has shown that the design of consumer directed policies tends to reduce health expenditures. If people with individual policies tend to have less expensive total claims than people with employer group policies, dropping them would inflate the estimates of actuarial value for the standard population.

Eliminating plans without claims of at least $5,000 is also likely to overstate the cost of covered benefits. In any given year, relatively few people have high health care claims costs. Willey et al. (Health Affairs, 2008) reported on average spending by people drawn from a managed care database of 26.8 million people in 2004/2005. In their sample, median spending was $989. Mean annual health spending for the plan population in normal health was $3,075 for both out-of-pocket and plan costs. People with chronic disease spent more, with mean spending of $8,225 and median spending of $3,321. For the severely ill, mean spending was $29,273 and median spending was $9,300.

After selecting its sample, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adjusted the data in a variety of other ways that could produce inaccurate estimates of average annual health care payments.

Utilization of “habilitative services” was assumed to be cost-free, raising the question of why coverage for services that have no cost is required by law. Kids’ dental care and eyeglasses payments were estimated, annualized and multiplied by expected participation rates, without explanation.

Only in-network services were used to calculate maximum out-of-pocket limits. HHS defends this practice with the statement that the data suggest that out-of-network services were seldom used, a situation likely to change given the narrow networks characteristic of exchange plans. Without any information on how claims for individual policies behaved, CMS simply assumed that “small group participation is similar to individual market participation in terms of age and sex distribution.”

All cost data were trended forward to 2014, and “[s]everal adjustments were made to this data to more closely represent the expected population of enrollees in 2014.” The report does not say how this was done. It also fails to explain how CMS arrived at the seemingly arbitrary spending brackets it used to determine cost shares. It imputed benefit characteristics to the brackets by age and sex, and used nonlinear least squares to estimate the actuarial value based on the imputed cost shares in each bracket.

The HHS methodology generates further cause for concern when it notes that the overall means of the groupings used to model the Bronze and Silver plans were “distorted due to random observations of extreme spending above the 99th percentile.” But Milliman reports that just 0.2 percent of a typical commercially insured population will incur more than $100,000 in allowed medical claim costs in a year, an occurrence rate that though not random would be small enough to fit the HHS description of extreme spending above the 99th percentile. HHS says that it dealt with those “random observations” using an unspecified “ad hoc” adjustment. Whether the ad hoc adjustment under or over-estimates plan spending for the actuarial value calculation is impossible to determine.

In the future, HHS plans to allow states to determine their own actuarial values. It would be simpler to end the individual mandate and replace ObamaCare’s regulatory rat’s nest of subsidies based on estimates piled on estimates with a tax credit for the purchase of health insurance.

Love the song pairing.

ObamaCare is a not a user-friendly program. The program is very specific and it is hard for the people to understand every single piece of the legislature. For me, that is one of the biggest issues with ACA. It is hard to implement a program that changes the healthcare system, when the consumers don’t know what they are doing.

The variability coupled with the lack of knowledge given to the general public is what is failing ObamaCare. The public should not be willing to accept an overhaul without proper education on the matter.

Disagree. The ACA exchanges are the easiest way for people to select their own policies that has ever existed. It takes the broker salesmanship away from the insurers and lets you do your own thing. I believe its called freedom,uncomfortable concept for some. The hard part is separating the legislation from the misinformation industry.

“Some of the more popular pre-ObamaCare individual policies featured deductibles of $5,000 with no additional cost sharing after the deductible. People who chose those policies knew their annual financial risk in advance. ObamaCare makes those policies illegal.”

Not so. I had an ACA compliant $5K policy with Blue Cross for the last 3 years. This year, the exchanges still offer the same Bronze $5k plan … but at lower premiums for me.

Yes, premiums might be more difficult for insurers to ascertain for the first couple of years but that’s why the ACA has backup fees for them. It will balance out nicely. According to Dr. Goodman, the bronze plans and higher deductibles encourage consumer discretion and edge provider prices down. Win, win.

“With overestimated actuarial values … all else equal, higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs also enable lower premiums”

This means that healthy individuals have incentives to enroll for insurance. If there is a concern that only the sick are enrolling, why having overestimated actuarial values is bad for the healthcare system? If young and healthy individuals enroll, shouldn’t this make the program sustainable?

The problem is that the young and healthy aren’t incentivized to enroll. The sustainability hinge on this segment of the market, but only are producing a small payout.

Overestimated values would inherently build a safety net since costs are likely to be lower than estimated, but estimates do need to be somewhat accurate.

“The standard populations differed, and the estimates of allowable deductibles ranged from $1,850 to $4,200.”

There should be some sort of standard in estimating the health expenditures. Meanwhile, it causes a wide and undependable range for deductibles that are estimated.

The costs are based on estimates, which are based on estimates. It is probable that their estimates contain errors. Eventually prices will adjust, especially when the values are calculated with real data. Once the market balances, the program should be sustainable.

But it is estimates which cause the bumpy start up issues that ACA has faced. In theory the program should be sustainable, but will it be?

“It would be simpler to end the individual mandate and replace ObamaCare’s regulatory rat’s nest of subsidies based on estimates piled on estimates with a tax credit for the purchase of health insurance.”

Agreed. Obamacare’s messy process of subsidies could greatly be simplified with a tax credit.

The premium subsidies are tax credits. The APTC are both advance-able and refundable. I think what you mean is, instead of a sliding scale of eligibility based off of income and deductions, everyone is actually treated equal and get the same tax credit.

According to the information presented by Willey et al. (Health Affairs, 2008) “relatively few people have high care claim costs.” Yet, the differences between the means and the medians suggest that there are some individuals that are spending a disproportionate amount of money on healthcare.

Key word being “relatively.”

Many policy makers who don’t have a firm grasp of financial risk management are delighted that health plans are standardized, and that actuarial values are standardized. I’m not convinced this will necessarily help enrollees, however. A better measure is the deductible and cost-sharing. For most people, this matters more than actuarial value.

What a mess. Thanks for the detailed analysis, John. Those of us who are veterans of the health insurance market know that the small percent of claims above $100,000 (my experience is that it’s higher than 0.2% of claims, as HHS assumes, but under 1.0%) are the claims that kill your plan. They are not “random” claims. An ESRD claim, coupled with kidney transplant, can run $500,000. And certain forms of acute leukemia can run well over $1.5MM. These claims overshadow all of the cost savings employers (and now taxpayers) can squeeze out of the other 99%+ of the population with wellness programs and cost-sharing.

Blake:

If the claims higher than $100,000 are insured through a separate catastrophic reinsurer, the premiums for the plan should be ubaffected if the incidence of those claims was close to what was anticipated.

I do not understand how the claims can “overshadow all of the cost savings employers (and now taxpayers) can squeeze out of the other 99%+ of the population with wellness-programs and cost-sharing.”

Those claims are supposed to occur. It is the number of claims that provides the increased or lower risk for the insurer.

Don Levit

You are correct. I like to use this example: assume I have a pool of 500 lives. 499 spend $1000 per year for health services for a total of $499,000. But one has an episode that costs $500,000. So this is a simplified way – using fairly reasonable assumptions – that a fraction of one per cent of an insured population can completely hit the overall costs. There are numerous examples of the so called 80/20 rule but in health care it is probably more like 90/10. If we can take the catastrophic costs “off the table” we eliminate the biggest financial risk – taking issues like preexisting condition limitations off the table, too. Frankly we created a situation where all of the effort is to make sure my insurance plan is not left “holding the bag” on the large claims. While controversial, we have done this historically for pensions, mortgages, crops, floods, etc. to protect against catastrophic situations. Despite the many abuses, the reason for doing this kind of thing remains. While it is complex, I argue it cannot be any more complex than the ACA.

This is the reason I keep advocating that instead of a complex approach like the ACA we would be better served to create a national ‘stop loss’

facility and leave much of the rest alone. If the Republicans and ACA critics are serious about proposing a replacement I suggest they look at something like this.

“When the actuarial value calculations were carried out, the amount of cost sharing that ObamaCare allowed depended upon the government’s estimate of the overall plan costs for plans that have not yet taken effect.”

That can indeed be a slippery slope.

The key point should be how to keep an active market which brings economic growth and innovations. A well-stimulated environment encourages people to earn enough money to buy healthcare by themselves. We cannot just rob Peter to pay Paul.

Great piece on AV today. Did you see my recent piece on the topic? http://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2013/12/12/obamacare_is_a_problem_for_much_more_than_the_5_100792.html

People who buy health insurance in the individual insurance market are extremely price sensitive. A high deductible in exchange for a lower premium is a good and fair tradeoff for young healthy people who want the peace of mind that comes with protection against catastrophic expenses that could result from a serious accident, cancer diagnosis, etc. The question becomes just how much is peace of mind worth? Someone with few or no assets may be perfectly willing to take the risk and declare bankruptcy if necessary. The only real negative consequence would be a ruined credit rating assuming he could find a hospital and doctors to treat him.

Separately, most insurers will tell you that the sickest 5% of patients account for 50% of claims in any given year, not 90% or 95% and they’re not the same people from one year to the next. There was a study in Health Affairs a few years back that showed that the sickest 5% of Medicare beneficiaries accounted for “only” 41% of claims in a particular year. If you looked at cumulative Medicare claims over a five year period, the sickest 5% for the full five years accounted for 27% of claims as some people had an expensive event one year and then recovered while others died along the way. As for reinsurance, I suspect that an attachment point of $100,000 would carry a pretty hefty premium as compared to a $250,000 attachment point.

Someone field this question for me.

Since the impetus of this blog is to recapture that free-market feeling, eliminate the oppressive government restrictions on the insurance industry, and let insurers accept or decline which enrollees they want as well as determine the level of premiums each customer should be charged … hey …why don’t we extend those same freedoms to Hospitals and Doctors?

Eliminate those pesky regulations and mandatory practices on providers. Let a hospital turn anyone away they feel might affect their profitability or liability. Let the Doctors charge what their ‘personal actuarial’ gut tells them to on an individual basis … or even auction their services. That would get that free-market freedom feeling back … or should there be different standards for the provider industry?

Should there be different standards for the provider industry? In a word, yes.

The problem is that health care services and providers run the gamut. As noted last week, there is a continuing problem with physicians gravitating to more lucrative specialties and locating in more affluent areas. If a pregnant woman now living in some rural areas of the country needs to go to a delivery room at a hospital, she may have to travel several hundred miles. She is hardly in a position to make a true choice as a consumer.

The same problem with certain drugs – an ongoing concern is that drug manufacturers focus of developing a “blockbuster” specialty drugs rather than medicines that might benefit more people and serve a preventive purpose at a relatively low cost because the blockbuster is far more lucrative. But if you are one of those needing that specialized drug – you can’t exert normal market choices.

If providers were free to use conventional market mechanisms, there is a high likelihood that those who are in poorer, rural areas will be in a difficult position with little or no ability to act like they would as a consumer of other goods and services. For example, in the Greater Palm Springs area there are world renowned hospitals serving very affluent patients but not far way are very low income populations with little to no access to even a community clinic.

As a friend likes to say after being afflicted while serving on a church mission in rural Central America – I am a health consultant but laying flat on my back in severe pain in a jungle in Central America – my knowledge of health care really didn’t help me at all. He could have said the same if his situation arose in thousands of small rural locations in the US. So I agree that there are parts of health care than will work like a market – there are many aspects that do not lend themselves to a market.

But don’t think the ACA is the solution, either.

“People who chose those policies knew their annual financial risk in advance. ObamaCare makes those policies illegal”

ObamaCare thinks we don’t know what is best for us.

John, you seem to regularly trigger a very thoughtful discussion. I would only add, to you and the others: What is the potential that the exchanges as established by the ACA of 2010 will improve the efficiency of our nation’s healthcare? Underlying this entire effort is that our healthcare industry is no longer affordable by our nation’s economy. In addition, the effectiveness of our nation’s healthcare has its problems, as measured by our nation’s maternal mortality ratio.

For our nation’s healthcare, how about your thoughts on its “social mandate” as opposed to solely its “economic mandate?” Other than funds for effectiveness research, the ACA of 2010 will do little to redress the disparities that underlie our nation’s healthcare. Fundamentally, we are willing to accept the disparities that exist between what our nation is willing to pay for healthcare and the substance of the healthcare that our nation receives in return, even if it is neither equitably available, culturally accessible, justly efficient nor reliably effective for each citizen.

Some factual corrections:

1. The annual ceiling on out-of-pocket expenses is not $6,250 as reported, but $6,350 in 2014 and rising to $6,750 in 2015.

2. The $2000 deductible ceiling (for single coverage) mentioned ONLY applies to the small group market, not the individual market as suggested. Further, there is an exception to the $2000 deductible ceiling that in practice allows virtually all Bronze plans and most Silver plans actually offered in the market to have deductibles over $2000. This exception is not uniformly interpreted and enforced by states, so you will see variability across the country.

I concur with your comments, although I’m not sure that the limit on out-of-pocket expenses will be as high as $6,750 for 2015. Was that published somewhere already? Regarding point #2, here is the language from the regulation allowing higher deductibles than $2,000/$4,000 for small group plans:

“A health plan’s annual deductible may exceed the annual deductible limit if that plan may not reasonably reach the actuarial value of a given level of coverage as defined in Sec. 156.140 of this subpart without exceeding the annual deductible limit.” (Sec. 156.130(b)(3))

As actuaries, we appreciate how difficult communicating on #actuarialvalue can be. Decided to put together a little musical video to help. Naturally, we had to choose big screen dramatic music.

http://bit.ly/1bOB73M