Myth Busters #9: Hysteria Over the Uninsured

After years of trying to do something about health care costs, especially hospital costs, through programs like National Health Planning, Certificate of Need, and Hospital Price Controls, the “health policy community” discovered the problem of Uncompensated Care. This, in turn, led to the discovery of The Uninsured — presumably the cause of Uncompensated Care (we are using proper nouns because these issues all quickly morphed from mere descriptions into titles for Great National Emergencies, like World War Two or the Great Depression).

This was a breakthrough. Here at last was an issue that would keep all the health policy wonks employed for a very long time. It is an issue that can never be solved! It can be converted into an annual CRISIS as each year the Census Bureau came out with new numbers and a new excuse to create new hysteria.

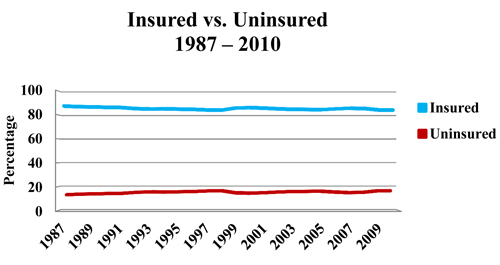

But, as the chart below shows, it has been about as stable a problem as anything could be. From 1987 through 2010 the proportion of the insured and uninsured has barely budged from roughly 85% insured and 15% uninsured. It has stayed the same during several recessions (1981, 2001, and 2009) and during boom times. It has stayed the same despite massive efforts by state and local governments to expand Medicaid, reform the insurance market, develop (and abandon) all kinds of “universal healthcare” programs, and grow new federal programs like S-CHIP.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Historical Tables

http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/orghihistt1.html (1987 – 2004) http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/files/hihistt1B.xls (2005-2010)

Actually, this whole dichotomy — that there is one group of Americans who are insured and another group who are uninsured — is false.

In fact, the American economy is dynamic, fluid, and diverse — and so is the uninsured population. This is beyond the comprehension of most of the academic elite, which wants to place everything in tidy little boxes.

Americans change jobs all the time. They have part time jobs, they are independent contractors, they work on commissions, they will take several jobs at the same time, they supplement their income by selling Avon or restoring houses in their spare time, they move from town to town and state to state, they will take six months off between jobs to go to school or travel to Europe, they live off their savings, or sponge off girlfriends and boyfriends, they engage in barter, they win lawsuits or a lottery, they receive a substantial inheritance. To the extent health insurance is job-based, it will always be “unstable.” It will come and go along with the jobs.

Health insurance, too, is diverse. Some policies are very rich; others are skimpy; some(like Medicaid) are rich on paper but pay physicians so little that it is difficult to get services. The people who are least likely to have health insurance are young adults in their 20s. These are also the people who are least likely to need health care services. They are also the people who are least able to afford insurance premiums since they are just starting out in their careers or change jobs frequently while deciding what they want to do in life.

None of this is bad. In fact, it is good because it is a reflection of the real needs and priorities of real people. It is an appropriate allocation of their scarce resources. Even “uninsured” young adults are likely to be insured for the things most likely to happen to them — traffic accidents and work place injuries. Young women, who may need more health services than young men, are far more likely to have it. At age 21 to 24, 35% of men are uninsured, compared to 28.8% of women. At age 25 to 34 it is 30.2% of men and 21.7% of women.

In fact, no one is insured for everything. In that sense, we are all partially uninsured. There is nothing wrong with that. Even people who are well-insured may not be able to get health services when they need them. The point of having insurance is not to have a card in your wallet, but to finance needed health services. Health insurance finances these services on a prepaid basis — we pay a little bit ahead of time every month so that the insurance company will pay the bill when it is incurred.

That is one legitimate way to finance the services, but it is not the only way and may not be the best way. It is every bit as legitimate to incur the bill and finance it through a credit card or bank loan. That loan is paid off in monthly increments after the service has been received.

Using health insurance is like a lay-away program at K-Mart. It is fine as far as it goes, but imagine trying to finance a car or a home that way. For those kinds of big purchases a bank loan is far more useful. Taking out a loan to finance expensive care will result in finance charges. But with pre-payment, one loses the value of the money while K-Mart (or the insurance company) holds on to it and adds their own administrative charges for managing the money.

For those reasons, it is actually more efficient to simply pay cash at the time of service whenever possible. One saves the financing cost of post-payment, and one saves the administrative and lost opportunity cost of pre-payment.

So, insurance has a role to play to health care financing, but it is foolish to think that it should have the sole or even primary role.

Next time, we’ll take a look at what is insurance, and what it is not.

Health insurance should work similar to saving for retirement. While young, most of our premium dollars should go towards a HSA since health risk is low. When approaching middle-age, a greater proportion of premium dollars would typically go to pay the higher cost for insurance — thus spending down the HSA. This type of insurance would be personal and portable. But that’s not the way it works. Currently, advocates for the uninsured want large pools of healthy people to cross-subsidize the higher costs of those with pre-existing conditions. This arrangement suffers from the weakness that people receiving subsidies have little reason to conserve resources. Also, if the age cohorts vary in size, the smaller cohort gets the worse deal.

I agree, there is a lot of hysteria.

A great post. Plus, because of empoyer-monopoly control of our health dollars, the correlation between having a job and having insurance is needlessly high.

There is a huge “cycling” of people through health insurance. For example, if we look only at people who were uninsured for the month of March, 1998, according to the Current Population Survey, 8 percent were uninsured for four months or less, 14 percent were uninsured for five to twelve months, and 78 percent were uninsured for more than twelve months. However, if you look at people uninsured for some time during the whole twelve months of July 1996 through June 1997, 45 percent were uninsured for four months or less.

If you draw the period out to two full years, 2006 and 2007, 89.6 million Americans were uninsured at some point in the two years. However, even for the two years, half of them were uninsured for eight months or less.

(For the sources of these data, please see http://www.pacificresearch.org/docLib/20081007_Presidential_Prescriptions.pdf.)

Third-party insurance is the source of almost all our problems in health care.

When I speak at meetings, I say that the poor do not need medical insurance, they need medical care.

The purpose of insurance is to protect assets against sudden depletion. When a person has no assets, he does not need insurance. He needs a place to go when he becomes ill. City and county hospitals used to work just fine.

Furthermore, Medicaid is not insurance, as those who carry the card have a hard time finding a physician, so his access to care is limited. Any gimmicks the government might use– like federally qualified health centers and Medicaid HMOs are simply a way to fleece the taxpayers.

Just a quick edit to your blog:

It has stayed the same [despite] BECAUSE OF massive efforts by state and local governments to expand Medicaid, reform the insurance market, develop (and abandon) all kinds of “universal healthcare” programs, and grow new federal programs like S-CHIP.

That’s a really fascinating idea. I think it works well for one-time events. The difficulty comes in financing care for chronic conditions.

How do you know that, Nancy? Gruber has found that such expansions crowd out private enrollment. Plus, the level stays the same during times of Medicaid contraction as well as expansion.

I think another source of our problem is our tax code, which heavily subsidizes employer-based health insurance. It is unfortunate that we don’t have some reform to offer the same deduction to individuals that you get via your employer.

In answer to Greg’s question:

http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2011/09/15/census-numbers-the-safety-net-is-working/

Whether you think this is a good thing or a bad thing depends on your ideological point of view. I think it’s a good thing.

Here’s the interesting thing

OK, so 15% chose not to carry “health insurance”, a (for now) voluntary product.

Filing a federal tax report is mandatory, yet 14.6% of people dont do it.

Having car insurance is mandatory in 47 states, yet 14.7% of motorists don’t own it.

Is there a correlation wihtin this approximately 15% of the population?

“Chose” not to carry health insurance? Your biases are showing. I hear from people every day, who have lost their jobs, run out (or can’t afford) their COBRA, are 58 years old with pre-existing conditions? Many can’t buy health insurance at any price, or if someone will sell it to them, can’t afford it, because they’re poor and unemployed. Hard to grasp the element of “choice” here.

Nancy,

I might have worded it better. Not all, but many of the 15% uninsured really are making a conscious choice not to carry health insurance.

Nancy, the Aaron Health Affairs blog post gives percentage changes in various groups from 2007 to 2010. It does not discuss whether those changes are statistically significant. It does not even bother to define what “government insurance” or private insurance is.

Greg’s graph, on the other hand, shows the fraction of insured and uninsured from 1987 on. The massive expansions in Medicaid and SCHIP that you refer to did not take place until the mid to late 1990s. If they were such an important factor, why did the insured fraction in 1987 look about the same as it does now?

Linda,

I think you have answered your own question.

Great piece Greg. I’m planning to do a “Health Freedom Minute” radio program on it. More people should be thinking about how this data is chronically being used.

In the end, it’s not about coverage. When you have no insurance, for whatever reason, or you lose the insurance you have today because of Obamacare’s higher premium costs or its prohibition against inexpensive catastrophic coverage — or when your insurer or the federal IPAB says NO to the care you need — it’s not about coverage, it’s about care.

Lots of people, including the “covered” (as Greg mentioned with those on Medicaid) will have their CARE denied.

Twila,

I’ve found that many consumers, especially those with limited means, are interested in “catastrophic coverage,” but as much as the term is thrown about, I’ve never seen a good definition of what it is. What’s your concept of it, and what about it do you think makes it inexpensive?

I’m not sure about extending the credit model to covering really expensive events works. Maybe for a birth or apendicitis it would. But who would give credit to someone with stage 4 colon cancer knowing it would never be paid off? Clearly that would have to be insured against. And creditworthiness is a thorny issue as well.

I like to say that insurance should only be for events that are the “4 uns”. Unpredictable, undesirable, unaffordable, and unusual. Even with that as a baseline (far from where we are), there are problems.

What’s unaffordable for some is not for others. In other realms of insurance we have variable deductibles, even up to ‘self-insured’.

But the biggest problem is the fantasy that everyone is ‘entitled’ to an infinite amount of health care. Resources are limited. And just like housing and food, there are – AND SHOULD BE – benefits to being wealthy. In my opinion, Uwe gets it EXACTLY wrong. To him, I would ask: should a refugee in Sudan get worse health care than the President? That’s the extended version of his “kid of coal miner or the CEO” query. Pretending there are no limits (Medicare, Medicaid, ObamaCare) does a great deal of harm. It creates the impression that I’m *entitled* to Bill Gates’ wealth because “I need a heart transplant”. I really have no idea why that would be true. Bill MAY want to voluntarily pay my bills, but it is MY bill. I shouldn’t have the government point a gun at him on my behalf.

Finally, of course, there’s the knowledge problem. Ideally, insurance companies would be liable for any change in ‘health status’ that occurs while the policy is in force, not JUST the health care expenses incurred during that time. That would solve the death spiral and the pre-existing conditions problem. There are none pre-birth and any discovered during life would be compensated when discovered.

Today’s “catastrophic coverage” is usually a misnomer… it is usually only for ‘minor’ problems like broken arms and the like… not cancer. At least the policies offered to college students are of that ilk, with limits under $100K.

True catastrophic coverage would essentially be a “real” insurance policy. No pre-paid health care whatsoever, no coverage for common conditions, no coverage for a common pregnancy (desirable, right?), no screenings (everyone should do them, right? by definition, not unusual), no coverage for inexpensive things, no coverage for completely avoidable events (like, say, heli-skiing or car racing, which would need a separate policy), etc. That’s the policy I want. Not the “unlimited everything (the IPAB approves) you need with very low out of pocket costs” policy ObamaCare requires me to buy.

Nancy, you wrote

—-

“Chose” not to carry health insurance? Your biases are showing. I hear from people every day, who have lost their jobs, run out (or can’t afford) their COBRA, are 58 years old with pre-existing conditions? Many can’t buy health insurance at any price, or if someone will sell it to them, can’t afford it, because they’re poor and unemployed. Hard to grasp the element of “choice” here.

—-

I would be careful about accusing others of bias when you are citing selected anecdotes as evidence. Obviously not everyone choose to be uninsured, but many do – myself included.

Also , you wrote

—-

In answer to Greg’s question:

http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2011/09/15/census-numbers-the-safety-net-is-working/

—-

Aaron is once again putting a tiny bit of evidence under a microscope and blowing it up. I was looking at the mega long term trend, and showing that nothing the policy makers have done has made any difference at all. My argument is this is because they constantly oversimplify complex issues. As they have also done with National Health Planning, Hospital Rate review, Certificate of Need, Managed Care, and just about everything they touch. These efforts have wasted money and destroyed lives

@Nancy Metcalf,

Let me propose a way to decide which is the better way to report these figures, i.e. the Greg Scandlen/Linda Gorman way vs. the Health Affairs’ blog (and pretty much everyone else’s) way.

Suppose we were looking at similar data for employment, instead of health insurance. Suppose we compared employed people with unemployed people, and subdivided the unemployed people into those who received welfare and those who did not.

Would it make sense to take the welfare recopients out of the unemployed “bucket” and put them into the employed bucket because they are receiving income and the unemployed without welfare are not?

Would it make sense to increase welfare dependency such that when 5 percent of employed people lose their jobs, if all of them can claim welfare, there is no net change in employment because welfare recipients are “employed”?

Would that lead to good public policy or worse public policy? It would lead to dramatically worse public policy because politicians would “solve” the unemployment problem by increasing welfare. The 9.1 percent unemployment rate would drop significantly if wee added welfare recipients to the “employed”!

Clearly, counting Medicaid recipients as “insured” is misleading and creates horrible political incentives.

I totally reject equating unemployment with publicly funded health care and am glad that Medicaid, however flawed, limited, and grossly underfunded, exists. I don’t agree it creates horrible political incentives.

For people who have disposable income and decent credit and who liove to read, shopping at a bookstore like Barnes and Noble is a delightful experience.

For people who have no money but also love to read, a public library is pretty satisfying also. The library may have skimpy hours and you have to bring the books back, but in 90% of the country you can find about 90% of what you want. (I was employed in a library system for years.)

This model of free enterprise plus a taxpayer-funded public sector works very well for adult education, which is certainly an important part of our lives.

We should have this model in mind for health care also. If you can afford private insurance or can get it from your employer, great. If you cannot afford insurance, there should be a county hospital and a community health center.

Now the public library model will not work overnight in American health care,

for at least the following reasons:

a. Some parts of the USA never had county hospitals in the first place.

b. Some county hospitals have been privatized in the last 25 years, often in a corrupt and ugly process.

c. Many cities and counties would be unable to raise taxes to pay for county hospitals. There will have to be federal funding, which conservatives will resist.

d. Even if we had enough public clinics and hospitals to cover all emergencies,

often a patient needs to start on new drugs after the emergency has subsided.

We may need a form of Medicaid for drugs, though with co-payments and much use of generics.

So there are many challenges to a public library model. However, there is no shortage of brainpower in the health care field. I would like to see us move in this direction.

Incidentally Michael Cannon, who is very conservative, has said several times that there other ways to help the uninsured besides a massive federal takeover of insurance. I would like to see more proposals in his spirit.

But this will take taxes at some point. The good news for conservatives is that a public health system would be much cheaper that guaranteed issue health insurance and subsidies for everyone to buy it. You could have 500 free public hospitals and 5,000 community clinics charging sliding scale fees for a federal outlay of probably $40 billion a year. ObamaCare will spend that much in a month.

Thanks, Bob. I agree, but I approach it from a different perspective. There is a large segment of society for which any form of health insurance will not work. They can’t understand the policy and can’t figure out how to use it. I was looking at some Medicare enrollment information yesterday and it was nearly incomprehensible even to me.

Please review Goodman’s elegant proposal for taking care of these issues. Everyone gets a tax credit for $X. Those who want to can apply it to their insurance premiums, those who don’t will have their credit applies to a safety net system of providers.

I liked Goodman’s proposal when I first read it, thanks for bringing it out again.

I do have some concern about where the safety net providers are going to come from — but when the federal spigot is turned on, providers of all kinds (including some dishonest ones) seem to materialize overnight.

Going back to an earlier post in this sequence, it would be refreshing to see the concept that the government is not responsible to pay for every treatment to prevent every death. Instead, going back to my library model, the duty of government would be to pay for a place that provides health care.

That is somewhat of a British NHS approach. It is not utopian but it is fiscally realistic.