It’s All the Doctors’ Fault

A recent press release from Health Affairs puts the blame for America’s health care problems squarely on them Greedy Doctors. It says:

Research appearing in the September issue of Health Affairs shows that physicians in the United States are paid more per service than doctors in other countries–in some cases double. There is also a far bigger gap between fees paid for primary care and fees paid for specialty care in the United States, compared to other countries. These higher fees in turn lead to higher incomes for US physicians than those earned by their foreign counterparts, and are the main driver of higher overall spending in the United States on physicians’ services.

Well, not really. The article, “Higher Fees Paid to US Physicians Drive Higher Spending for Physician Services Compared to Other Countries,” by Miriam Laugesen and Sherry Glied, is a pretty thin reed on which to hang such a sweeping conclusion.

In fact, the article shows how difficult it is (nearly impossible) to compare service payments between countries, something the authors acknowledge, though they prefer to call it “challenging.”

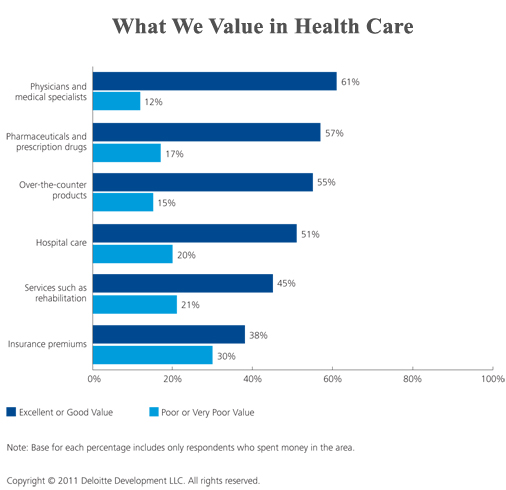

As you’re reading what follows, keep in mind the following chart from Deloitte, which found that the majority of U.S. consumers feel they get their money’s worth in out-of-pocket spending on physician services.

Laugesen and Glied look at primary care and orthopedic surgery (hip replacements) in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, France and Germany, but the payment system is different in each location, and the “service” may be defined differently as well. All of the countries involve a mixture of public and private payments and some have private payers supplementing the public payment. The authors go into great detail about these “challenges,” but still not enough to make sense of it. For instance, surgeons in Germany are salaried, so how do they allocate the cost of a hip replacement against other services? They don’t say. Many of these countries allow physicians to bill on top of the regular payment, but it isn’t clear how much. In the U.S. private payer data on physician payment is proprietary, so the authors rely on HealthGrades reports, which may or may not be reliable.

But the authors satisfy themselves that they have squeezed out enough payment information to write about. Then, to get to “net physician income” they subtract “practice expenses” from the gross. But they don’t have a word to say about what they mean by “practice expenses,” how those expenses may vary between countries, or how they determined how much they cost. Presumably, the expenses will always include rent, utilities, staff salaries, and malpractice insurance costs, but what about physician time devoted to administration? Is that included or not? We don’t have a hint.

The authors take some time to consider educational expenses, which in the U.S. is typically born by the physician, but not so much in other countries, but again this issue is more complicated than the authors are willing to admit. The closest they come is in noting that primary care physicians in the U.S. earn $27,000 more than those on the U.K., which is more than enough to offset the $21,300 annual cost of tuition for the American physician. Well, yes, I suppose it is — assuming everything else is equal, which is a big assumption.

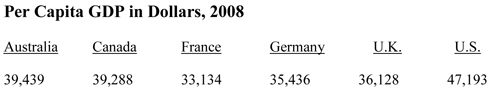

Towards the end of the article, the authors also discuss (a little bit) the fact that higher physician payment in the U.S. may be due to the fact that all professionals in this country command higher wages than in those other countries. Medicine has to compete against business, engineering, law, and other high-earning professions to attract competent people. In one of their tables the authors report on per capita GDP and find the U.S. is much more prosperous than the other countries:

But they don’t try to factor this into their conclusions at all. They might, for instance, have averaged the per capita GDP of the five other countries ($36,685) and found that the U.S. is higher by 28.6%, and used this “relative wealth factor” to adjust their results. But, no, that would not suit the pre-determined narrative of the Health Affairs editors.

Meanwhile, there are plenty of other questions that go unaddressed, including:

- Is the bundle of services the same in each country? What tests are performed during a visit with a primary care physician? Does the surgical fee for hip transplants include follow-up visits or rehabilitation?

- In some countries physicians pay for their health insurance through taxes while in the U.S. they pay with after-tax income. Why not account for that difference in comparing incomes?

- Physicians in the U.S. make much use of Physician Assistants and other “physician extenders.” Is the same true in other countries? If not, don’t American physicians have more unpaid supervisory responsibility than in other countries?

- Similarly, an inordinant amount of physician time in the U.S. is spent on dealing with insurance company paperwork, prior approvals, appeals, and reviews. This time is subtracted from patient care and billable hours. Do other countries have similar issues?

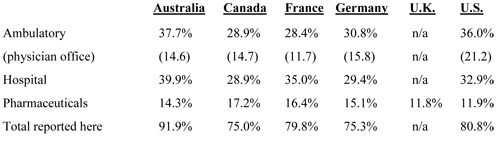

- Finally, a table included in the article shows a wide variation in how health care expenses are allocated in each country:

This table raises all kinds of fascinating questions, such as where does the rest of the money go? Presumably some of it goes to nursing home or dental care, but is it credible that Australia has virtually none of these services?

I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, but these researchers have done us all a disservice by not even asking them or trying an answer them. Sadly, this is another example of “research” that is selected to support a predetermined conclusion.

Is it any wonder that nothing we ever do in health policy actually works?

Physician care is a small portion of National Health Expenditures. I don’t know how higher national spending can be blamed on higher physician fees. I realize in the pursuit of revenue doctors might order costly tests. But, if anything, reducing physician fees could motivate doctors to order even more excessive treatments to maintain their income (absent a competitive market).

Thanks for posting. This is a great commentary on publishing things that sound good but actually don’t have all that much meaning.

In Canada, where I am from and used to work, docs are paid by the government. At times, doctors incomes will be published in the newspapers. This tactic successfully invokes class warfare with envy and resentment of the doctors because the doctors tend to make more than the average unskilled laborer. The quoted incomes invariably are a gross figures that do not account for office overhead or taxes. Nor do they include the income of residents. There is also no mention of the debt most medical students graduate with (albeit it does not tend to be as high as in the U.S.)

This strategy is effective at demonizing the doctors as the source of the healthcare woes in Canada even though physician fees are typically only about ten percent of health care costs. When the provincial medical associations “negotiate” the fee schedules with the government, there is no public sympathy for the docs. Something to look forward to when we (doctors) are public servants here in the United States as well.

Does paying doctors less actually save any money? Pay should be market prices based on supply and demand.

Blaming doctors seems like finding a scapegoat.

A candidate for worst study of the year from people who should know better?

That’s the problem, they know better but publish this tripe anyway. GIGO. Totally useless stuff.

Liberals believe that doctors provide a public good that ought to be universal and free. Getting rich off of someone’s misfourtune is immoral and evil. But PLEASE don’t apply the same standard to trial lawyers or union bosses!

This kind of research leads to catastrophic policy conclusions. We could execute the same research for barbers in the U.S. versus Bangladesh, discovering that American barbers earn a multiple of what their Bangladeshi counterparts do.

(By now, the economists reading this have had the name “Baumol” pop into their heads.)

The more productive a country is, the more expensive labor-intensive services will be versus less productive countries. That is why pretty much all professionals in the U.S. earn more than their foreign counterparts.

Of course we could reduce physicians’ nominal incomes, without reducing their real incomes, by reducing the cost of being a physician: malpractice-insurance premiums, cost of medical school, et cetera.

Another factor worth considering is the per capita supply of physicians, which is lower in the U.S. than most other industrialized countries. That, on it’s own, may contribute to the higher pay of U.S. physicians. And it can be pinned directly on the licensing laws, rather than any market process.

So it very well may be that doctors are overpaid in the U.S.

The study referenced by Greg is not the only one on this topic.

Also see

http://businessroundtable.org/studies-and-reports/health-care-value-comparability-study-full-report/

Greg is right. It is extremely hard to make 100% valid cross-national comparisons or, indeed,intra-national comparisons — e.g. NY vs California, not even to mention Texas. Thus the Laugesen-Glied study leaves a good number of questions unanswered.

The response to that condunrum could be : (a) because we cannot be perfect, don’t do anything, or (b) do the best you can with the data at hand and challenge others to do better. Most health policy research proceeds on the latter basis, in full knowledge of the fact that the typical health-services research papers appearing in HEALTH AFFAIRS proceed on the latter basis, in full knowledge that these analyses are still analytically sounder and more accurate than is the typical annual report of a business corporation. I taught accounting for many years and know whereof I speak.

Perhaps the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute do perfect studies. Could be. Alas, we can’t all be perfect.

Greg mentions that:

“Similarly, an inordinant amount of physician time in the U.S. is spent on dealing with insurance company paperwork, prior approvals, appeals, and reviews. This time is subtracted from patient care and billable hours. Do other countries have similar issues?”

Why that should make the heart of American patients who have to pay for this overhead jump with joy beats me. Presumably Greg will tell us that patients get enormous benefits from this overhead expense. I may not find that perfectly believable, however.

Best,

UER

Ah, Uwe, read again the press release from Health Affairs — “Research appearing in the September issue of Health Affairs shows that physicians in the United States are paid more per service than doctors in other countries–in some cases double., etc.”

They apparently don’t share your reticence about drawing definitive conclusions. I hope you will help correct them.

Regarding — “Presumably Greg will tell us that patients get enormous benefits from this overhead expense.” My friend, you really need to pay more attention. I have spent the past 20 years trying to REDUCE insurers’ (and employers’) role in health financing.

Yer pal,

Greg

John,

Thank you for your commentary on this study. I can’t help but wonder if government policy might contribute to the relative gap in national spending between primary and speciality care. In the U.S. if you have an infection (say a child’s ear infection), in order to get a doctor to write a prescription the parent and child must make a visit to the doctor’s office.

How do other countries deal with this? I don’t know about Germany and Australia but in some countries basic pharmaceutical drugs (like antibiotics) are over the counter, in others nurses can provide a prescription, in some countries that don’t value primary care you would go to an emergency room or urgent care setting and many patients forego that option due to the hassle of long waits or unavailability. Under any of those three scenarios, the patient would not be seeing a primary care physician. This could explain at least some of the disparity.

Because the U.S. has put in a regulatory regime that demands physician prescriptions, Americans are going to use the system that is least demanding of their time and money and for many that means they will make a primary care office visit. Our FDA tightly controls access to pharmaceuticals, whereas other countries do not. Does anyone know how Germany or Australia address this issue?

Additionally, I can’t also help but also think that we might pay primary care doctors more because we value that kind of care more than other countries. Since we do value primary care so much, the market sets the prices based on demand. This isnt’t a bad thing it is simply the way markets work.

I find it truly amazing that America can have the obesity rate we have (and all it associated diseases and consequences like diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle) and our life expectancy is not that different than other countries with much lower rates of obesity. This is due in no small part to our doctors and medical system. But providing care to treat these conditions is expensive.

The bottom line is that the market is working well. The best things the government could do to lower costs is for government to get out of the way and put patients in charge of their health care dollars and make them better consumers. If patients understood that there is a financial cost to many of their life choices, and they had to quantify those choices every day, I think we would become much, much healthier as a nation.

Thank you for the critique. Now let’s get it to the main stream!!!

HealthAffairs is no longer the serious journal it once was. My colleagues no longer submit manuscripts there. The journal should be read like Time or Newsweek, not serious research.

@JSB Which journals would recommend?

In response to a poorly conceived article with conclusions that cannot be drawn UWE writes:”(b) do the best you can with the data at hand and challenge others to do better. Most health policy research proceeds on the latter basis, in full knowledge of the fact that the typical health-services research papers appearing in HEALTH AFFAIRS proceed on the latter basis”

I guess that is where health care economics differs from medical care. In providing care for patients, if the data and conclusions drawn from the study are bad they aren’t supposed to be used whether or not they are published in a journal.

While cross national comparisons are imperfect, I do believe that the price differences in the US vs. other Western Nations are quite troubling. We can argue that relative price differentials as a matter of purchasing power may account for higher real price differences, but if that’s the case shouldn’t we at least have a similar quality of healthcare?

For example, if I adjust big mac consumption for PPP I expect that quality (and quantity) of my big mac(s) to be relative from a PPP perspective. In most cases we would expect that the more expensive American big mac may be of slightly higher quality then the less expensive Vietnamese counterpart. Quality comparisons may not be 100% but in general western consumption of goods adjusted for PPP are similar to those of goods in developing nations.

However the US ranks at the bottom of almost every single conceivable health care metric in the world. We’re the worst at dealing with preventable diseases. We have the worst infant mortality of the western world and we have lower life expectancies then the rest of the western world. Regardless of how we slice it, we not only pay more as a % of national gdp and more in normal dollars (though perhaps at parity from a PPP perspective) and get a far far far poorer outcome in terms of results.

While doctors aren’t the sole problem, we have to realize that the incentive structures in the American system promote actions that result in increased services, but not better outcomes. We may push for more tests because of higher malpractice costs, but is it necessary to also push for more invasive surgery when the outcomes don’t result in better care? Specifically is it better to push for more invasive procedures when there’s a growing amount of evidence that it may actually be detrimental to the patient?

I don’t claim to have an answer, but there is a systemic issue in American healthcare which is resulting in a sub optimal, pareto inefficient, allocation of resources relative to outcomes. The French, German , and Japanese systems produce a much higher quality of healthcare, at a lower cost (relative to national gdp) without shortages on the supply side. I don’t think that malpractice suits, insurance overhead and higher wages can account for the price differences as well as the quality of care differences present in the American system.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/08/14/some-medical-tests-procedures-do-more-harm-than-good.html

http://www.thefreemanonline.org/featured/ranking-the-us-health-care-system/

http://www.photius.com/rankings/healthranks.html

http://www.amazon.com/Healing-America-Global-Better-Cheaper/dp/1594202346

• Is the bundle of services the same in each country? What tests are performed during a visit with a primary care physician? Does the surgical fee for hip transplants include follow-up visits or rehabilitation?

o Regardless of the composition of the bundle – US treatments result, in general, in far poorer results.

• In some countries physicians pay for their health insurance through taxes while in the U.S. they pay with after-tax income. Why not account for that difference in comparing incomes?

o Taxation would suppress aggregate demand, however all of the European nations place caps on total deductable payments and often exclude chronic conditions from deductibles. This in turn would promote access to healthcare and should result in a higher consumption of goods (especially relative to gdp). A good example of this is Medicare after the prescription drug benefit (consumption of medical goods increased and is projected to continue increasing)

• Physicians in the U.S. make much use of Physician Assistants and other “physician extenders.” Is the same true in other countries? If not, don’t American physicians have more unpaid supervisory responsibility than in other countries?

o This is may be true, lower salaries for doctors could result in lower assistant in Europe. However, given the increased number of procedures in the US, we could argue that assistants allow US doctors to increase the capacity of services they offer by freeing up doctor time. This in turn brings us back to the point above, that we run more tests, more surgeries etc… but have far lower outcomes so our increased output is not resulting in a better slate of “goods” to the public

• Similarly, an inordinant amount of physician time in the U.S. is spent on dealing with insurance company paperwork, prior approvals, appeals, and reviews. This time is subtracted from patient care and billable hours. Do other countries have similar issues?

o Wouldn’t this in turn support the French/German/Japanese systems where a nationalized plan with a combination of private doctors and private/public insurance companies that are mandated to make payments in a short period of time the right way to go. Does this support the argument that price controls a la France may help doctors by freeing up administrative costs. It at the very least makes a strong argument for national health cards that allow doctors to reduce the amount of paper work and make most of their filing electronic and automated.

• Finally, a table included in the article shows a wide variation in how health care expenses are allocated in each country:

o Allocation may be varied, but we are unquestionably at the bottom of the pack on almost every single healthcare metric measured by WHO. Though to be fair we do have some of the best cancer survival rates in the world.