New Health Care Law: The “Individual Mandate,” Tax Exclusion, Tax Deduction, & Tax Credit

According to Judge Roger Vinson’s decision on January 31, Congress has no power to legislate an “individual mandate,” whereby the federal government charges the citizen a “penalty” if he does not buy a private health-insurance policy. As an opponent of ObamaCare and a supporter of the Constitution, it’s a decision that I cheer. But as an economist, I find it absurd. If last year’s majority had designed the legislation slightly differently, it would not have prompted the smallest whisper of constitutional challenge.

To understand this, let’s look at a very simple society comprising two equally productive households: Smith and Jones, under four different scenarios.

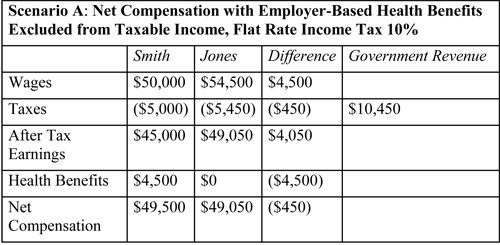

Smith earns $50,000 and receives non-taxable employer-based health benefits worth $4,500 for total compensation of $54,500. Jones earns cash wages of $54,500, but receives no health benefits. They pay a 10 percent flat rate of income tax (with no deductions). We don’t know why Jones has forgone health benefits in exchange for more cash wages, but we know that the flexibility of cash is worth at least $450, because that’s how much extra tax she pays as a consequence. The government’s total tax revenue is $10,450. Although oversimplified, scenario A is the status quo in U.S. health care.

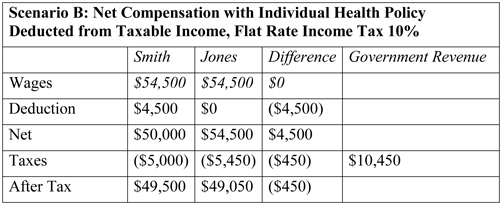

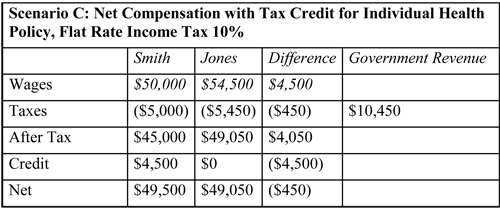

Now, suppose we want to free the individual to make his own choice of health benefits, instead of passively accepting benefits chosen by his employer. In scenario B, the benefit is transformed into a deduction, which the taxpayer can claim if he buys a qualifying health policy. In scenario C, the benefit is transformed into a tax credit.

In this simple, static analysis, all parties should be utterly indifferent to how the government labels the way it gives a tax benefit to the consumption of health care. In each scenario, employers pay exactly the same amount of remuneration; Smith and Jones enjoy the same net compensation; and the government takes the same tax revenue.

Once we introduce income inequality and progressive income tax, things get more complicated – but they can still be managed. More important is that individuals will consume health care differently (at the margin) if they are spending against a tax credit versus a tax deduction (as discussed by Dr. Goodman here), and will make better decisions if they choose their own policy instead of accepting one chosen by their employer. But that is not the point of this article.

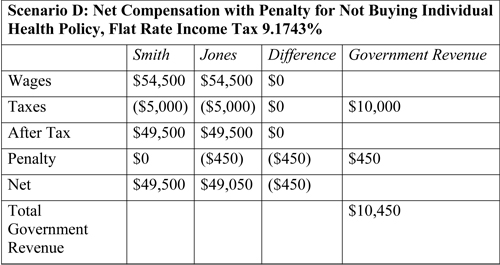

All three scenarios described above can be discussed soberly in conservative and libertarian circles. However, once we introduce the terms “individual mandate” or “penalty”, the discussion immediately erupts into rancor, loathing, and litigation. The “individual mandate” is described in scenario D.

In scenario D, the flat rate of income tax drops to 9.1743 percent; the government gives no special tax break to Smith for his health benefits; and also levies a penalty of $450 on Jones, because she has not paid for qualifying health benefits. All parties – Smith, Jones, their employers, and the government – should remain utterly indifferent to which scenario is adopted and enforced by the IRS. (This remains true for any tax rate and for any change in income for either Smith or Jones. Try it yourself by downloading the spreadsheet here.)

However, all parties are not indifferent to these four scenarios. Indeed, scenario A is enshrined as sacrosanct employer-based health benefits that Congress touches at its peril; scenarios B and C are interesting scholarly proposals that get little traction in the Beltway, and scenario D violates the U.S. Constitution! On the other hand, Mitt Romney is also wrong in claiming that the individual mandate satisfies an uninsured citizen’s personal responsibility to pay his medical bills: There is nothing that prevents Congress from specifically allocating Jones’ “extra” $450 payment to fund uncompensated care in any of these four scenarios.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m thrilled that Judge Vinson found the individual mandate unconstitutional, because real health reform cannot happen until ObamaCare is defeated. But let’s not forget that the president’s faction could have achieved the federal takeover without it. And they will surely try another approach if Judge Vinson’s ruling is upheld.

From a societal standpoint, there is very little difference between families using pre-tax dollars to buy their own policy (assuming they could); and workers who forgo cash wages and obtains coverage through a job. This holds as long as workers are happy with the status quo. However, the ACA would force some residents to purchase coverage they otherwise would not purchase; and fine them (or their employer) when they fail to do so. Part of the problem is the ACA forces people to purchase the coverage upper middle-class public health advocates assume everyone should have without taking into account people’s demand for health coverage varies with age, income, health status and risk aversion.

John, you are too rational. Haven’t you learned by now, people in health poicy are emotional. They do not thinhk syllogistically.

Good analysis. Amazing, how people get hung up on distictions that don’t matter.

Obama cooked his goose by claiming that the fine for being uninsured was not a tax (since he promised not to tax the middle class). Then in court, the administration argued the opposite. The judge refused to allow that kind of hypocrisy.

Good job, John. As usual.

The central point of the post seems to be that to see things as an economist means to see things purely in terms of net finances. I disagree. That is seeing things like an accountant.

Economics is not accounting. You don’t just whip out a calculator (or a spreadsheet), hit the enter key, and out pops economics.

To borrow a phrase, economics is about human action. There are potentially important differences among scenarios A, B, C, and D, even if the financial numbers come out the same (though I suspect even those are a bit too pat to be representative).

To put it briefly, to say that it should be a matter of indifference to whatever imaginable means are used, so long as the net outlay in cash is the same, is poor economic reasoning.

It is no more true than arguing that it should be a matter of indifference to me if I give a homeless man $5, or if he takes it from me — after all, it is the same amount.

If the “economics” applied is blind to the substantial differences between those two scenarios it is bad economics.

Thomas L., could you explain the “substantial differences” in the scenarios given?

@Thomas L.

You are right that issues are seldom as simple as we would like them to be, but likewise it is difficult to understand the problems without reducing them to the most basic proposition. If a solution is flawed at the most basic level it can certainly not be less flawed as it becomes more complicated.

The simple truth is that there is no longer (if there ever was) a valid reason for different tax treatment for personal vs. employer sponsored health insurance. This is not to say that employer sponsored plans do not have advantages (as well as disadvantages). Rather it to be clear that the government should not make this call. As you point out “one size fits all” health plans are in no way economical from a utilization standpoint, and the one thing of which you can be certain is standardization of everything possible is the hallmark of government involvement. And the leveraging potential through preferential taxing gives the government every opportunity to do just that.

@Frank

Well, part of it has to do with the real-world being so much messier than Mr Goodman’s examples.

For one thing, who in America is operating with a flat-rate 10% income tax? Does anyone thing one is coming? Mr Goodman finds the judge’s reasoning “ridiculous”, which was rather condescending, but then starts off his own examples with the economic equivalent of a, “now assume a spherical cow…”

To start with example A in a more real-world scenario, the health insurance might very well cost something like $10,000/y to provide, but the employee “pays” only 45% of it. That means the employee has the option of getting $4,500 extra income, or a $10,000 policy.

Their taxes will be something like 30%, meaning the cash option is only worth ~$3,150 after taxes. That places a strong incentive to buy a $10,000 policy for only $3,000. And once you’ve got it, with all those bells and whistles, might as well use them, which drives up health care prices.

Since under A only employers can give this magic “10 for 3” option, almost everyone will take the ten, and the long term trend is to push more and more income into the pre-tax realm. Since most companies have many employees, this also tends to bump up “one-size” fits all plans that cover everything imaginable. $10k becomes $11k becomes $12k, etc. Especially since the employee “part” is only ~45% of that, every move of $1k looks like a move of only $450 (and only $300 in forgone, post-tax wages), the upward creep always looks like a deal. Maybe I don’t want to participate in that, maybe I want cheap insurance, but if cheap insurance post-tax costs me $5, and great insurance pre-tax costs me $3, great insurance is cheaper than cheap. Maybe silly, but totally true.

Likewise, my being the 1 guy in 1000 that wants more $3 more cash rather than $10 more health care means there is no way I’m going to get the company to give me my full $10,000 of forgone compensation.

However, under some variation of B or C, anyone can get a policy with pre-tax dollars. That would tend to undermine the monopoly of employer provided plans and similarly undermine the attractiveness of one-size fits all plans. The more people that opt-out of the employer plan in order to get their own, the less pressure there will be on the one-size upward creep, and the more pressure there is to realize the entire value of the compensation from opting out (ie, $4.50 eventually rises towards the full $10).

I know that isn’t perfectly stated and airtight–this is just a short comment–but my point is that is a lot going on here with incentives to employees, employers, group buys, participation rates, &c. than Mr Goodman’s 10% flat-tax world shows, and I didn’t care for the arrogance of flatly calling people that think so “ridiculous.”

Back on topic, in the past, I know http://keithhennessey.com/ had some good posts on the interesting and odd incentives under various pre/post/credit tax schemes. Might be worth checking out some more detailed analysis than I can provide there.

Oops, he said “absurd” not “ridiculous”. What I get for responding days later without rereading the original post…

Thomas L.:

There are behavioral differences between the four scenarios. However, that wasn’t the thrust of the article. The primary behavioral difference is between employer-monopoly health benefits and individually based health benefits, to which the entire literature on consumer-driven tax reform is dedicated.

Within the realm of individually based health benefits, there will be difference in behavior at the margin if the individual receives a tax credit versus a tax deduction, because the deduction reduces the marginal cost of every single health transaction, which a credit does not.

However, if the “penalty” for disobeying the individual mandate is a fixed penalty, there should be zero behavioral difference between that and a tax credit. If the penalty is a sliding scale based on income, there should be zero behavioral difference between that and a tax deduction.

To your homeless man: If the government wants you to give $5 to a homeless man, does it matter if it gives you a tax credit if you hand him the money, or fine you if you do not? There is no difference.