Myth Busters #10: Risk Pooling

In terms of the evolution of public policy, the “health policy community” failed at health planning, failed at hospital rate setting, failed at Certificate of Need, and failed to do anything about uncompensated care.

Not only had it failed, but it spent fortunes and destroyed lives in the process.

Then the same people turned their attention to the uninsured. I mean literally, the exact same people. The people who were unable to tell hospitals what facilities should be built or how much to charge for their services decided they could reorganize the insurance business. Hubris? Ya think?

This opened up a whole new world for them. Suddenly they had to learn some of that insurance lingo so they could sound like they knew what they were talking about. Suddenly health policy academics were buzzing with terminology like “risk pooling” and “adverse selection.” Unfortunately, they couldn’t quite grasp the meaning of the terms.

Take risk pooling. These health policy elite use the expression “risk pool” in two contradictory ways. Both are wrong.

First, they think of it as a giant pool of unallocated money everyone contributes to, and withdraws from when they have a need. They see it like taxes. Everybody pays taxes, which can then be fairly allocated based on each person’s need (and the whim of the government.) Some people will have a lot of needs, others not so much, so we need lots and lots of people contributing to the pool so that no one person will have to pay too much. The bigger the pool, the better.

The other way they use it is to defend employer-sponsored health insurance over individual coverage. Employer coverage is better, they think, because it pools risk.

Let’s start with the first one — the giant pool of money. This understanding places the emphasis on “pool” and ignores “risk.” It leads to a “tragedy of the commons” phenomenon in which every member of the pool tries to grab as much as he can before it is depleted.

The emphasis should be on “risk.” What is being pooled is the risk of a loss, an adverse event. The point is not to have a giant pool of money, but a pool of people (risks) large enough to cover expected losses. A risk is (and must be) an uncertainty. No one can know ahead of time who will incur a loss or when it will happen. But, it is possible to calculate the likelihood of losses for a large group of people, and divide that likelihood by the number of people covered to determine how much each should pay to cover these losses.

Each individual member of the group may have a higher or lower likelihood of incurring a loss and ideally there will be a mix of people to balance out the probabilities. Most insurance will assess each member’s risk and adjust the premium to reflect that greater or lower risk. Obviously these rate adjustments do not account for all of the variation in risk or there would be no point in having the insurance in the first place. Most members of the pool will pay far more than they will collect in benefits, but we are willing to make that payment “just in case” something bad happens. Even with spending all that money, we would much prefer to never collect. It is far better to never be in a traffic accident or have your house burn down regardless of how much you pay for insurance.

Importantly, in this scenario there is no pool of unallocated money. Each dollar is contractually obligated to pay for a loss. We have a contract with the insurance company that we will pay $Y premium to get $X benefit in the event of a loss.

Now, a risk pool does need a minimum of enrollees to be effective, but it is simply not true that the bigger the pool the better. Actuaries generally set the minimum number at 25,000 covered lives and place the optimal number at about 60,000. See, for instance, Elinor Hall, “MediCal Managed Care Models Context Considerations,” March, 24, 2006.

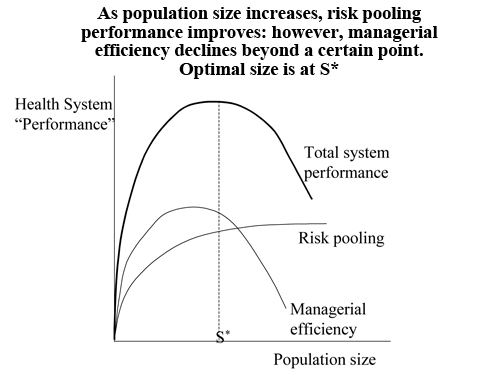

This number provides all of the advantages of risk sharing that are possible. There may be some economies of scale in exceeding that number, but these, too, are limited. A study by the World Bank found that the efficiency of any health insurance arrangement peaks at some number determined by both the size of the pool and the limits of managerial efficiencies. (See graph.)

This raises the other use of the term that policy makers have been using — that employers are good vehicles for insurance coverage because they “pool risks.”

No they don’t. Employers actually concentrate risk. A national employer with over 25,000 workers may be a reasonable risk pool, but the employees of a 75-person print shop are likely to be more like each other in their risks than the general population. They work in the same place, live close to each other, are of similar ages, incomes, and education, and are exposed to the same environmental hazards. Further, they expose each other to the same diseases.

Employer-based coverage may have some marketing efficiencies over individual coverage, but it is the insurance company’s job to be a risk pool, not the employer’s.

In a future post, I’ll look at one of the consequences of this misunderstanding of risk pools — mandated benefits.

Greg does a great job explaining the concept of pooling risk. I hear policy wonks talk about it all the time. They erroneously explain it as the need to get healthy folks in the pool to offset the exorbitant costs of the unhealthy folks. That is so wrong. These wonks basically want to gouge the healthy to subsidize the unhealthy. That is not pooling risk; rather it subsidizing risk. True risk pooling involves risks of an equally unknown nature — not combining unequal risks.

It has always been clear that sick people cost more on an annual basis than healthy people. The reality is that it is a very small part of the population that knows beforehand what group they are in from year to year.

Most policy people assume that people should have the same benefits when they are sick, even though they purchased (or didn’t purchase) their insurance assuming they were going to be healthy.

Most of the people are healthy most of the time. Despite the fact that many of us are grossly overweight or have bad habits, we continue to be healthy from year to year despite the facts.

Not a sermon, just a thought.

Nice explanation, Greg. Can’t wait for part II.

Interesting subject Greg. Actually I personally think 25,000 is a bit high as the “minimum” for determining “risk credibility” for cat health coverage, but the point is well taken.

I think your closing comment is salient and bears repeating.

“Employer-based coverage may have some marketing efficiencies over individual coverage, but it is the insurance company’s job to be a risk pool, not the employer’s.”

As always it is still a battle to get people to understand that anything that doesn’t involve the element of risk should not involve insurance.

Very instructive article. I look forward to your article on risk pooling leading to bad ideas like the individual mandate.

I really liked this discussion. There is something about the concept of risk pooling that I find fascinating.

I had never thought of employers pooling risk as a concentration of risk. But, you’re right it is, especially in places where workplace hazards like asbestos or dioxin exposure is a problem. I would bet that coal mines and chemical companies have known that for years.

Looking forward to part II.

An outstanding article, Greg. Only one error: This is not “evolution” of health policy – but devolution!

Most health-policy scholars confuse pooling the risk of future events with averaging the costs of current health status across a population.

Can these scholars explain why people are able to pool risk when they buy automobile insurance as individuals? Or homeowners’ insurance? Or travel insurance?

Well functioning insurance markets are hiding in plain sight. One is tempted to think that the health-policy experts to which Greg refers are willfully ignoring what doesn’t fit their ideology.

John Graham says,

“One is tempted to think that the health-policy experts to which Greg refers are willfully ignoring what doesn’t fit their ideology.”

That’s right John. Until the “experts” come to the conclusion that paying for low end routine healthcare expenses have nothing to do with proper use of risk shifting (insurance), they are not only misusing the concept, but they are merely pursuing a social agenda.

Frank and John,

I will have to write about this pretty soon. My contention is that the people who do “health policy” around the country aren’t very bright, despite all their PhDs. Being well-educated but not too bright leads to a number of behaviors —

1. They are insecure and terrified of being challenged.

2. So they cluster together in tight little circles of like-minded people — group think.

3. That leads them to mock and ridicule anyone with a different point of view, especially if that view comes from experience in business.

4. They endlessly repeat the little slogans they learned in school, like Roemer’s Law. They clutch these mantras like a talisman.

5. They ignore any evidence that is contrary to their pre-determined point of view.

6. Finally, like trained monkeys, they have learned to do statistics, but statistics are not science and do not lead to understanding.

At least this has been my experience in 30 years of dealing with these folks.

Excellent post, Greg!

I agree with Frank; this is my favorite line.

“Employer-based coverage may have some marketing efficiencies over individual coverage, but it is the insurance company’s job to be a risk pool, not the employer’s.”

BTW: For what it’s worth, an actuary with BCBS recently told me that a group of 1000 usually has a risk rating factor similar to the population at large.

A ‘pool’ is who you let in the pool… and in fact as Greg notes, once the ‘pool’ gets very large/ inclusive, it’s then just population based health care, in most cases prepaid 1st dollar coverage… voila… socialized medicine!

Most of the insurance industry is purposely including dissimilar participants in ‘the pool’ so they don’t have to price high deductible policies at lower rates that reflect the reduced insured payouts associated with HDHPs, especially the highest deductible plans.

We know these higher share of cost plans reduce excess utilization (lower overall spending) along with the 1st $10k+ NOT an insured expenditure, HDHPs should be much less expensive than 1st dollar coverage; but they are not.

Until competition changes that fact, we’re stuck on the same old tread mill, building a consolidated infrastructure for the ultimate transition to government run health care… ugh.

Good point Beverly. It has been my experience in the administration of self-funded employer plans that “stop loss” insurance provided by an insurance company becomes redundant at about 2500 employer lives. In other words, when tested over a long period (say ten years), the claims expense for this size group becomes 99% “predictible”. This means that a properly funded and reserved employer of this size may have no use for insurance risk shifting at all.

This is significant because the logic can be applied proportionally to smaller risk pools that need “some” risk protection but can still “predict” a significant percentage of its health plan usage. As we consider smaller groups the amount of necessary “risk shifting” increases. A group of 500 lives may be able to predict its expenses to 80% accuracy (which means it needs to buy insurance to account for the unpredictible 20%).

The point is that the logic can be taken all the way down to the individual who, even as only one person, does not need to “shift risk” to an insurance company for every dollar spent on healthcare. That is to say an individual can finance his own “predictible” healthcare expenses (possibly through an HSA), and only buy insurance coverage for unpredictible expenses (true risks to that individual). If the insurance premium is properly discounted for the reduced risk the overall cost of financing an individual’s healthcare is significantly reduced (when compared to the “group think” (as Greg notes) insurance benefit standards that most people apply to the cost of healthcare financing.

The bottom line that paying for healthcare expenses through a third party financing mechanism (insurance) is very costly, and only those healthcare expenses that “must be insured” should be financed that way.