Brookings: The Unaffordable Care Act Lowered Individual Premiums

Significant premium hikes in the Obamacare exchanges have been in the news lately. A Dallas Morning News article recently proclaimed, ‘When your health insurance is bigger than the mortgage, something’s wrong’. Indeed, insurers are charging premiums that about the size of a car payment on a late model used car. For a family the premiums are sometimes as high as a mortgage payment. Yet, insurers are hemorrhaging money – suffering losses to the tune of billions since Obamacare went into effect.

But apparently my perception is dead wrong. A pair of Brookings scholars argue individual premiums are actually lower than they would have been absent the Affordable Care Act. What???

That’s the argument a couple of Brookings scholars making. The Brookings Institution is a centrist to slightly left-of-center think tank that is well respected for not letting politics cloud its analysis. At least, Brookings didn’t allow politics to influence its research until now. The following is an excerpt by the Brookings scholars that appeared in the Health Affairs blog recently. Here’s what they had to say about Obamacare in California:

Covered California, that state’s marketplace, just announced premium increases averaging 13.2 percent. But even if premiums increase by the 10 or 15 percent overall that some are predicting for 2017, they will still be far lower than premiums otherwise would have been in the absence of the law.

2014 Premiums In the ACA Marketplaces Were 10-21 Percent Lower Than 2013 Individual Market Premiums (emphasis theirs).

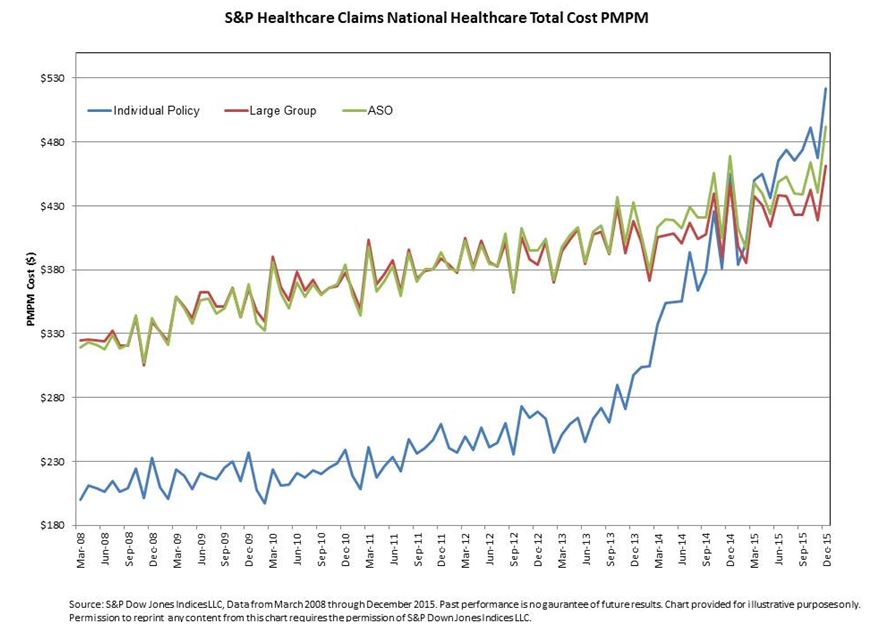

Writing in the Apothecary blog in Forbes, Mercatus Center economist, Brian Blase does a smack down with the Brookings scholars explaining why their results are inaccurate. Dr. Blase methodically builds his argument and carefully explains his reasoning as only an academic researcher can. His desire to present his findings in an understated, unbiased way is hardly necessary. There’s an old saying in literature, “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Blase uses a graphic that shows average monthly per member costs going back to 2008. See if you agree with Brookings that individual premiums after the ACA are lower than they would otherwise have been. (Click on graphic to enlarge).

The way I read the graph below is the average per member per month cost in the individual market was about $200 in March 2008. That sounds about right. When people have to pay their own insurance (blue line), they tend to shop for high-deductible plans. By contrast, large group plans (red line) are considerable higher because benefits are richer and workers cannot be turned down due to pre-existing conditions.

Notice the monthly cost of individual plans did not begin to skyrocket until the fall of 2013. That was about the time insurers had to begin gearing up for the highly regulated plans under Obamacare. By December 2013 some of those more costly plans were beginning to be reflected in the average cost of premiums. From December 2013 to June of 2014, the monthly cost increased from about $275 to $390. That’s an increase of about $1,380 a year that Brookings doesn’t believe actually happened. by September of 2014 the cost was almost $420 per month. By December 2015, the monthly cost of an individual policy was about $520. In about 7.5 years, individual premiums rose from about $200 to more than $500. But Brookings thinks Obamacare actually lowered premiums.

The goal of Obamacare to raise the premiums on Individual Medical (IM) is a success. The problem was if Individual Medical cost is less then the healthy employees would leave for IM and leave employers with the sick.

Obamacare extended the life of employer-based health insurance a few years but the corruption cannot continue much longer.

I’m sure corrupt Hillary has the solution and will tell us all about it tonight.

Blase provides a blahzay analysis

Hard to get the accent over the “e.”

Devon, when I wrote the 1st tax-free MSA, effective date 1/1/97, it was a 24-year-old male with a $2,250 deductible and the premium was $24 a month. Gasoline was $1.19 a gallon in April 1997.

Today gas is up 70% to $2.02 a gallon and health insurance would be $40 a month today if it went up 70%. Health insurance goes up more rapidly than gas with all of the government involvement and running all of the insurance companies out of business to create giant Blue Cross monopolies in the states.

Didn’t you say Medicaid cost over $500 a month last year for a low quality HMO that pays NOTHING if you go out of network? Blue Cross loves those Medicaid contracts.

We know how to provide inexpensive coverage for healthy people. Just let insurers refuse to cover people who are unhealthy or already sick. The issue is how do we provide coverage for that population and how to we pay for it or at least subsidize it? Under community rating and guaranteed issue, the premiums are what they are whether we’re looking at an employer plan or an ACA exchange plan. If you want to restore the pre-ACA IM market, offer a mechanism to cover the people who will be declined by insurers selling IM policies.

So, what are the options to finance subsidies sufficient to bring high risk pool premiums down to a level that the unhealthy and already sick can afford? We could raise income taxes across the board. We could increase the FICA payroll tax rate. We could have a dedicated value added tax (VAT) of 5% or so. We could just borrow the money and add to our debt for the next generation and the one after that to pay off which, of course, is a lousy idea.

I remember a number of years back when Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts complained to Partners Healthcare, owner of Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital among numerous other facilities, about the high reimbursement rates it demanded to be paid, the CEO of Partners told BCBSMA, “This is what good healthcare costs.” As we see from the graphs in this post, the current premiums for both employer plans and ACA exchange plans reflect what comprehensive health insurance cost today based on community rating and guaranteed issue.

I know that healthy people want to pay a much lower premium that reflects their lower health risk profile. However, going back to underwriting and telling the unhealthy and already sick, tough, you’re on your own isn’t who we are. Is it?

Barry, you want to let employer-based plans terminate their sick people and then have people on individual insurance pay for it.

To do this you must take away the FREEDOM of healthy people to purchase low-cost permanent and portable individual insurance where they are safe.

Barry, you should just support that employer-based health insurance should not be able to terminate their employees’ insurance, ever. Your problem is solved.

Your liberal answer is not the only answer. Why should self-employed people pay for big business to shed their liabilities?

I’m sure Hillary will come up with a liberal solution tonight that you will love Barry.

Vote for TRUMP and repeal Obamacare.

Barry you always have valuable insights. As you allude, there is no plan design that will magically make everyone happy. There are arrangements that benefit the young and healthy; and there are arrangements that benefit those older in poor health.

Over the past few months I’ve tried to engage people in an honest discussion of what is possible; and what is reasonable. We will never get a handle on rising health care expenditures by mandating everyone chip in the equivalent of a second mortgage so everyone can gorge at the All-You-Can-Eat Health Care Buffet.

The real problem is that 5% of the population is consuming $1.5 trillion in care annually; equal to all the care consumed by the other 95%. I believe 1% is consuming 20%. If the U.S. really wants to slow spending, it has to focus on the 5%. How can we get them better care at a cheaper price? How much of the 20% of care spent on 1% of the population is futile? Is there a way to get people to save for the day when they become the 5% (or 1%)?

For the government the easy solution is to deny patients nothing by requiring everyone have comprehensive coverage (that are increasingly becoming high-deductible health plans).

At some point the United States has to come to grips with the fact that resources are not unlimited. A “mortgage payment” that provides Americans with a lifetime spent in a home may have more value to them than a mortgage payment sized premium that provides an extra month of life if they get cancer.

Public policy needs to focus on the 5% of patients, who half the money is spent on.

Devon – Thanks for your response.

As you noted, it’s generally accepted in health insurance circles that in any given year, the sickest 1% of members account for about 20% of medical claims and the sickest 5% of members account for 20% of claims. The complicating factor, however, is that these are not the same people from one year to the next. A few may be but most are not.

I can point to myself as a classic example of what I’m talking about. Since 1999, I needed three high tech heart related interventions. So in three of the past 17 years, I was expensive to insure. In the other 14 years, I was inexpensive. My six generic drugs cost less than $1,000 per year combined. A checkup, a stress echo and maybe a wellness visit and a couple of other primary care visits cost no more than another $1,500 at most. There are probably millions of people like me including lots of them on Medicare. Yet, we all would be considered uninsurable if we had to pass medical underwriting to get health insurance in the IM market.

The need for healthcare is unpredictable. Even healthy people can suffer injury from a car accident, motorcycle accident, or a sports related injury among other possibilities. Healthy and athletic middle age people can need knee replacement surgery or even a hip replacement or hip resurfacing. Most people probably couldn’t pay for needed care when such an event occurs without incurring debt. They can also suffer heart attacks without warning or be diagnosed with cancer. I was perfectly healthy until my late 40’s. Stuff happens to people. That’s why they need health insurance, at least to cover the expensive events that require hospital based care.

As for what’s reasonable care and what’s excessive care is subject to considerable debate. What role does defensive medicine play? How do normal medical practice patterns in the U.S. differ from practice patterns to treat similar diseases and conditions in other countries? I don’t know.

While we can’t make everyone happy and satisfied, I think we need to find a way to ensure that everyone at least has insurance coverage for catastrophic events.

Hips, knees and cardiac procedures are becoming commodities nowadays. These are procedures that have the a lot of bang for the buck. What is less certain is care for people who drift in and out of the hospital because of poor care coordination, poor self-care, dementia and poor health literacy.

“This is what good healthcare costs.”

A hospital CEO may say it, but that doesn’t make it so. I don’t know if it’s so, or not. I’ll bet most Americans don’t know, either. And why shouldn’t we know more than we do, about such a vital and costly service?

Barry, you know that one of my long-time beefs is that US policy makers and pundits so often seek to reduce “healthcare” costs by fooling around with insurance mechanisms – when the underlying problem is the cost of delivering medical care. Insurance is about the allocation of costs – spread of risk, if you prefer. But even the optimal allocation of costs won’t reduce delivery costs. That tells me we can’t permanently address the insurance part of the cost problem until we pay a lot more attention to delivery cost.

Why does good medical care cost so much? I think good medical care is provided in France, in Germany, in Switzerland at lesser cost than in the US. Are they doing things we are not? Are they not doing things we are? What is the role of public health programs in other countries vs the US? Why is knowledge about other countries delivery systems not a prominent part of the US public debate?

I think the information is available, and I think it should be the focus of the analysis. For example, how is a 14-ounce preemie treated in other countries? Or a frail 89-year old with a terminal illness? It’s conceivable that Americans would prefer high cost medical care if we really understood the alternatives. As it is, I think many Americans simply assume other countries insurance programs are less costly because of factors related to insurance. I think that’s a mistake; the public needs much more information before we can react intelligently to the Health Partners CEO comment.

I’ve also felt for many years our public debate is like a man looking for a lost watch on a moonless night. The man felt the watch slip from his wrist over there, in the dark. But he’s looking for it here, under the street light – because it’s so much easier to see over here. Are we focused on the cost of insurance because it seems to be a much simpler problem to solve than the cost of medical care? Are we also looking in the wrong places?

John – I think you and I are on the same page about the fact that it’s high healthcare costs that account for why our health insurance is expensive. It always bugs me when liberals start railing about high CEO compensation at the large health insurance companies. Even if the 25 most highly paid executives at each of these companies all worked for free and the savings were used to lower health insurance premiums, it wouldn’t be enough to move the needle more than a tiny fraction of 1%. It’s ridiculous.

As for comparing the cost of care and the composition of care between the U.S. and other developed countries, I think the issue is multi-factorial.

In his 2003 paper published in Health Affairs titled “It’s the Prices, Stupid,” Uwe Reinhardt and his co-authors talk about considerably higher prices per service, test, procedure and drug in the U.S. We know that brand name and specialty drugs cost considerably more in the U.S. than they do in Canada, Western Europe, Japan and Australia because those other countries use price controls and marginal production costs are very low. The pharmaceutical industry counters that our free market environment ensures that U.S. patients get access to new drugs sooner than patients in other countries and if we were to impose price controls, it would slow the pace of medical innovation. The VA drug formulary, for example, is extremely restrictive. Most U.S. patients wouldn’t tolerate that approach as a way to save money.

Another issue is that doctors are paid more in the U.S. than they are in other countries and I personally think that’s appropriate given how much time they have to spend training before they can practice, the hefty cost of medical education in the U.S., and the high opportunity cost of what they could earn in more lucrative fields like finance and real estate with fewer years of education needed to boot.

Defensive medicine is another issue that plays a role but is impossible to quantify with any precision. I think it’s highly likely that our litigation environment is taken into account when the specialty societies develop practice patterns that may be different, more thorough and more expensive than what prevails in other countries.

End of life care and its cost is subject to wide debate. Doctors will tell us that they’re not very good at predicting when the end of life will occur most of the time. What’s the definition of futile care? If a patient with late stage cancer wants to try a new experimental treatment that has only a 5% chance or less or working and the cost is high, who should tell him he can’t have it, if anyone? On the other hand, languishing indefinitely on a feeding tube and vent with no reasonable prospect of recovery probably is wasteful. In the socialist countries, part of the social compact is that you don’t impose unreasonable costs and expectations on your fellow citizens. In America, it’s I want what I want when I want it and I expect someone else to pay for it.

The area where I would most like to see cost comparisons between the U.S. and other countries is in operating hospitals. How many employees per licensed or occupied bed are there in U.S. hospitals vs. comparable Canadian and European hospitals? I have no idea and I’ve never seen a study that addresses that issue.

While we’re at it, let’s have price transparency including disclosure of actual contract reimbursement rates.

Barry I agree (no surprise) the delivery of hospital care needs to be examined first because that’s where the money is.

Remember the night Princess Diana was killed? The Paris emergency vehicle just stayed on scene – and stayed and stayed. I was wondering why it didn’t rush off to the hospital,the way any ambulance in the US would have done.

I eventually learned that in France, emergency vehicles are equipped like mini-hospitals, so there is more immediate essential treatment available, and less delay driving to a hospital. That’s a real difference in how medical care is delivered.

Another anecdote, also in France: an elderly acquaintance of mine had cancer surgery a number of years ago. He lived alone in a rural area in the South of France and had no family — at least, none nearby. The local medical system sent what I can only describe as a “medical taxi” to bring him 10km to a clinic where his follow up treatment took place. In the US, try getting an ambulance for that. That’s an example where the French medical system is more integrated into the social system that in the US.

I’m not suggesting the French system has no problems, and I certainly don’t know as much as I’d like about the French system. But every time I learn something about other countries’ systems, I wonder: why aren’t our so-called thought leaders bringing us this kind of information? Why aren’t they helping to clarify the meaning of these differences so we can understand them? Because they aren’t.

John – One thing that always struck me as strange about Western Europe is that middle class people, I’m told, live in tiny houses or apartments by our standards, drive tiny cars or mopeds, gas is the equivalent of $8.00-$9.00 per gallon and restaurant meals cost twice as much as a comparable meal in the U.S. and for a smaller portion at that. Yet, somehow, healthcare is a lot cheaper.

On vacation in Venice a few years back, a member of our tour group fell in her hotel room and hit her head. A water ambulance was called to take her to the local hospital. She required a few stitches and they examined her for a concussion before releasing her to return to her hotel. The total bill came to €35 or about $50 U.S. at the time. The water taxi back to the hotel cost €60. Go figure.

One thing I learned about the French system relatively recently is that most women give birth in a birthing center instead of a hospital and are assisted by a nurse mid-wife. They have a procedure room in case she needs a caesarian but there is no NICU on site and who knows how far it is to the closest hospital. I hear from doctors that things can go south pretty fast if something goes wrong during the birth.

I suspect but don’t know for sure that the most significant factors that account for our higher costs are (1) prices per service, test, procedure and drug are higher in the U.S., (2) defensive medicine is a more significant issue driving costs than in other developed countries and (3) rescue care is much more aggressive both at the end of life and the beginning of life in the U.S.

I also think that our hospitals have more employees per licensed or occupied bed, more single rooms, probably larger rooms, more amenities like art work, fancy lobbies, nicer floors and the like. Foreign hospitals and doctors’ offices for that matter are a lot more Spartan than ours at least for the most part.

I am suspicious of prices, too, even though we were speaking of delivery costs. I think it’s closest to ideal when payers can compare prices and products, and make their own value decisions. If that could be accomplished, payers would have little reason to care about the relationship between a hospital’s prices and its costs.

But there are obstacles to doing that. There can be significant differences between an admission diagnosis and a discharge diagnosis – thus differences in costs, and therefore prices. The most frequent reasons for admission won’t necessarily be the same from hospital to hospital. Transparency thru comparative pricing won’t work in areas served by only one hospital – and there are lots of those. Which underscores the fact that a purely competitive market in which under-performers might disappear doesnt fit the needs of one-hospital towns.

So is the only alternative that hospitals be regulated as public utilities? Looking around at the efficiency and innovation present in most public utilities, I hope not. But unless better ideas emerge, I think that’s where we are headed – and there is no shortage of people pushing us in that direction.

John – Here’s some interesting data I came across recently showing comparative healthcare price data from seven countries including the U.S. It’s from the International Federation of Health Plans.

http://static1.squarespace.com/static/518a3cfee4b0a77d03a62c98/t/578d34649de4bb15e7a9f2e2/1468871781348/2015+Comparative+Price+Report_Final+071516.pdf

The utility model for pricing of hospital based services may not be a bad idea. I happen to have data for my own cost of electricity and natural gas going back to 1975 including usage data. Over that 40 year span, our price per kilowatt-hour of electricity increased 256%, natural gas per hundred cubic feet (CCF) rose 400%, and the Consumer Price Index rose 445%. The natural gas has always been there when we needed and the electricity has almost always been there with the glaring exception of a 10 day outage during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Other than that occasion, we were never without power for more than a day or so in the 43 years that we’ve lived here. That’s pretty reliable service in my book. The company earned reasonable returns over that time and was easily able to attract the capital it needed to sustain its business model.

Of course, electric and gas utilities are natural monopolies because they are so capital intensive. It wouldn’t make economic sense to have duplicate sets of power lines and gas lines in the same town competing for customers.

Hospitals are capital intensive businesses too but not to nearly the same extent as the utilities are. Moreover, the long term secular trend is toward less need for hospital inpatient care and a greater share of most hospitals’ business and revenue is moving to outpatient care. I note, though, that emergency room care and overnight stays designated as observation status are part of outpatient care. As fewer inpatient beds are needed, more hospitals will downsize or close.

When there is only one hospital for miles around, though, they can’t just be allowed to charge what the traffic will bear when the product they offer is not something people buy because they want to but because they have to and that care often has to be delivered under emergency conditions. This isn’t like buying a new car, computer or TV.

When I’ve talked to Medicare Advantage plan executives, their primary focus is keeping frail seniors our of the hospital — because that’s where the money is spent.

It is interesting that when I recently attended a stakeholder meeting on the state of health care the only thing the doctors, benefits brokers/ TPAs, HR people, policy analysts could agree on was: 1) patients need to take more responsibility; 2) doctors need to work more closely with patients to better coordinate their care; and 3) hospitals are a huge driver of high, unnecessary costs.

I wonder what the benefits brokers, TPAs, HR people, policy analysts, and hospital officials agree on when they meet?

The thought reminds me of Adam Smith: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices”.

😎

I’m told that two of the most common conditions that generate a disproportionate number of frequent visits to the ER are congestive heart failure and mental illness. I’ve also heard that insurers have recently been working more closely with providers to develop payment models to better manage these high risk and high cost patients through such strategies as using nurse case managers and social workers along with home visits to assess needs and the patient’s home environment. The nurse case manager can also play an important role in coordinating care, making follow up phone calls and home visits as necessary and the like.

As for hospitals performing lots of unnecessary care and generating high costs in the process, I think some of that might relate to defensive medicine in response to our litigation environment. This phenomenon is exacerbated by the fact that doctors practicing within the hospitals are often interacting with patients they don’t know especially when the patient was admitted through the ER. For example, if a patient presents complaining of chest pains, how thorough and how costly is the workup done at the typical U.S. hospital to either rule out or identify a heart related issue as compared to a similar workup in other developed countries? These costs can add up pretty quickly.

Yes, unnecessary care in any setting drives up overall medical costs, but I see that additional cost as distinct from the cost of delivering care in the first place.

Doctor Evo Shandor would probably agree. 😎

https://youtu.be/a4TPo8eYEs0

Let me go back to the Blase and Brookings article.

I surely do not have mastery of all the data, but let me raise one brief point.

Before the ACA, many individual market insurers played rather sneaky games with different “pools”.

They would bring out a low priced new plan but you had to pass strict underwriting to get it.

So healthy person moved out of old contracts, while unhealthy persons were stuck with the old stuff.

So you did wind up with healthy insureds indeed paying $200 a month, and unhealthy older insureds paying $700 a month or just dropping coverage.

I only bring this up to say that it is darned hard to say what the average premiums really were before the ACA.

The ACA premiums may or may not be worse on average. All we know is that ACA premiums are a lot more public.

Bob, Blue Cross of IOWA used the old pool trick and they would use it in their renewal letters.

You selling Blue Cross should know all about their tricks.

Note to Barry on lower costs in European hospitals:

Their hospitals are indeed less lavish and their care is indeed less aggressive…..but that is not the only difference.

In Europe (and Singapore, and Israel, and to some degree Australia), a large portion of hospital expenses are financed by broad based payroll or income or sales taxes.

The patient is only charged a fraction of the real cost.

In other words, when your friend in Venice was charged 50 euros for her care,that is not because Italy has learned how to deliver ER care for 50 euros. It is because the total cost may be 500 euros but taxes pay a big part of that.

Reminds me of American fire departments. About 15 years ago I had a fire on some property that I owned. Several engines came and maybe 10 firefighters, and the blaze was contained with no injuries.

I got a bill for $250. The idea was to punish anyone who set fires carelessly. The total accounting cost of what was done was probably $5,000.

How this translates to American hospitals is very tricky.

County governments in parts of the US used to fund hospitals with taxes, but that was very unpopular.

Bob — I understand but the fact remains that all the data tells us that the U.S. spends five to six percentage points more as a percentage of GDP on healthcare than any other developed country. Are you suggesting that the portion of hospital costs financed by taxes rather than prices charged for patient care is not factored into those numbers? I would be surprised if that’s the case. If it is, then it’s been a wrongheaded debate for years.

Bob, in your example of the fire department, an issue comes to mind. The fully-loaded cost to put out your fire may have been $5,000. Had your fire department been volunteer, the marginal cost would likely have been far less than $250. Granted, that would not count the cost of the building, the equipment, the overhead and so on.

Bureaucracies tend to expand. Counties that once had volunteer fire departments are encouraged to “modernize” and make their fire departments professional. Once part of the public sector, there is pressure to conform to standard benefits, including union wages, union benefits and deferred compensation that allows firemen to work 25 years and retire for the next 40 years on 85% pay. In the interest of training, every time an ambulance leaves the station, the “fire truck” often follows, which of course raises costs and requires higher capacity.

I’m not knocking firemen. I’m explaining what happens when public services are provided by bureaucratic organizations. That is the risk if counties decide to run hospitals. As I recall there are numerous hospitals across the country being propped up and kept open for political reasons rather than economic ones.

That said, the county where I grew up runs the 9-bed hospital and subsidizes it, the nursing home and the doctor/dentist/physical therapist and a couple other medical professionals. It does so in hopes the wealthy, retired farmers won’t move away to bigger cities with better health care once they retire.

Devon, you are absolutely correct about what happens when government provides services. The charge to “customers” goes down, but the ultimate cost to taxpayers goes up and up over the years.

This appears to be the case with VA health care. On the one hand, no VA patient has ever been harassed by a bill collector, which is a good thing. But the dead weight of salaries and benefits has steadily eroded the quality of care, and of course these personnel costs add to the federal deficit.

There is a difficult fine line to tread when it comes to analyzing privatization. In the area of prisons and in military matters, it certainly seems to this outsider that privatized firms cost even more than state firms and are frequently worse actors.

But you look at trash hauling in many cities, where private firms perform just fine at a fraction of the cost of unionized garbage collectors.

The best compromise seems to occur in voucher systems.

The government takes the responsibility for funding, but the government does NOT operate the service with government employees.

The trend to let veterans take their VA money and go to private doctors has a lot of promise. OF course the implementation of this program has been very uneven and probably corrupt, thanks to contracting snafus. Plus the VA will take decades to reduce its own staff.

Connecticut will be holding hearings this week for the three major insurers involved in its Obamacare Exchange: Anthem, Connecticare, and Aetna. Each is asking for premium increases that average mid-20%

Maybe Brookings didn’t sample any premiums in Connecticut.