What Republicans and Democrats Don’t Understand About the Insurance Company “Bailout”

Last week I testified before the House Oversight committee on the “risk corridors” in the (ObamaCare) exchanges. Republicans claim that this is a device to bailout the insurance companies. Democrats, in the unusual position of defending the insurance companies, actually claimed that the government was going to make a “profit” because of it. I was in the uncomfortable position of not agreeing completely with either side.

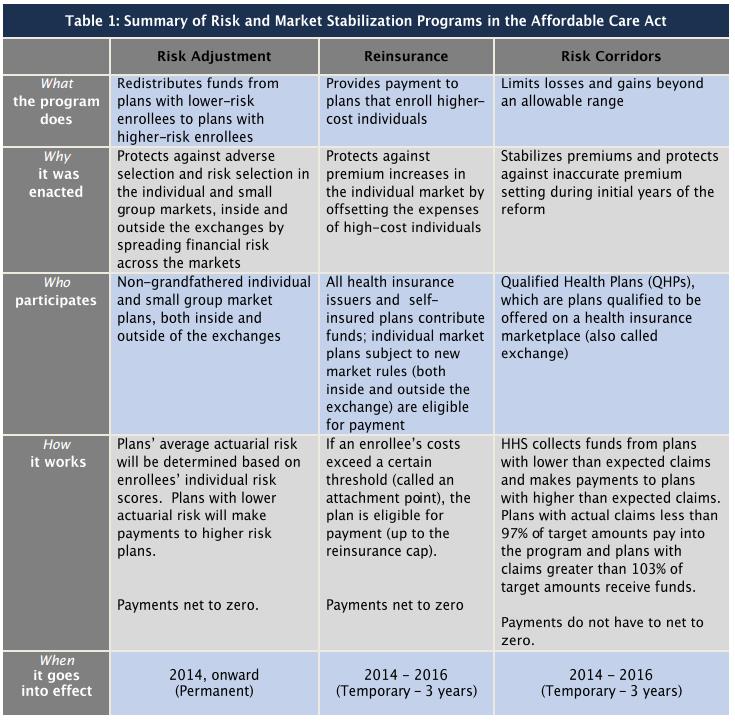

The Affordable Care Act creates a new health insurance marketplace (the exchange). But because of the great uncertainty about what buyers will enter the market and who will buy what product, the law creates three vehicles to reduce insurance company risk. Risk adjustment, a permanent feature of the exchange, redistributes money among the participating insurers, depending on the health status of the enrollees. That is, plans with healthier enrollees are “taxed” and plans with sicker enrollees are “subsidized.” Reinsurance allows insurers to hedge against the possibility of enrolling a very high-cost patient. This program lasts for only three years and the funds come from an assessment on all non-grandfathered health insurance sold in the country. These two programs are both deficit neutral, in the sense that outflows equal inflows. See the explanations by Greg Scandlen and John R. Graham and the summary chart below.

The third vehicle is the risk corridor, which basically redistributes funds from profitable insurers to unprofitable ones. Unlike the first two vehicles, however, this adjustment is not revenue neutral. If the entire market turns out to be unprofitable, the federal government steps in to subsidize some of the losses. In fact, there is potentially an unlimited taxpayer liability here — at least for the next three years.

By the way, did you know that there is a similar risk corridor in the Medicare Part D program — one that was never sunset? And because insurers are overall profitable in that market, the federal government actually is making an annual profit from the Part D risk corridor. In essence, seniors are overpaying for drugs and the federal government is pocketing the overpayments. (We’ll save this scandal for another day.)

Large amounts don’t grow on trees,

You’ve got to pick a pocket or two

(Source: Kaiser Family Foundation.)

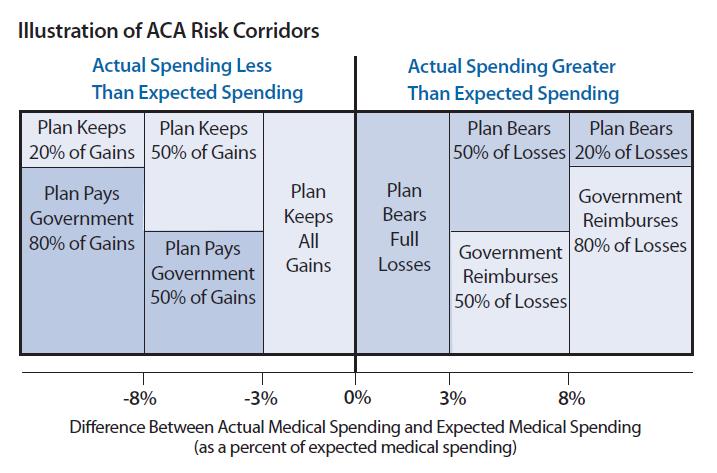

How the risk corridors work. Insurers in the exchanges are subsidized for their losses in the following way. If medical costs for a plan are in excess of 103 percent of its target costs, the plan will receive a subsidy equal to 50 percent of its losses between 103 and 108 percent of target. For costs above 108 percent of target, the plan’s subsidy will recoup 80 percent of the losses. The converse is that the insurers are taxed on their unexpected gains. Further, the tax thresholds are the mirror image of the subsidy thresholds. So there is a 50 percent tax on the gains for plans with costs below 103 percent and 108 percent of target costs, etc. (See the chart.)

ACA Risk Corridor Program (2014-2016)

(Source: American Academy of Actuaries fact sheet)

Why the risk corridors pose a potential burden for taxpayers. There are a number of reasons why the individual market could become a sicker, more costly pool for insurers. To the degree that happens, they must raise their premiums. But higher premiums discourage the healthy and the marginally sick from buying. As more of those decline coverage, the premium must be raised again. We could get a “death spiral,” in which the premiums go so high no one can afford then. Or, the premiums can be kept low by a steady stream of subsidies from the taxpayers.

Here is one problem: the federal (ObamaCare) risk pools will soon close their doors and send their enrollees to the state exchanges. This is the program that allows people who were “uninsurable” to purchase insurance for the same premium healthy people pay. All of the state risk pools are planning to do the same. These risk pools were spending billions of dollars subsidizing insurance for high cost patients. Now those subsidies will have to be implicitly borne by the private sector plans through higher premiums charged to everyone else.

To make matters worse, cities and towns across the country with unfunded health care commitments are readying to dump their retirees on the exchanges, nationalizing the costs. Since retirees are above-average age, they have above-average expected costs. The city of Detroit, for example, is planning to unload the costs of 10,000 retirees on the Michigan exchange. Many private employers face the same temptation.

Then there are the “job-lock” employees — people who are working only to get health insurance because they are uninsurable in the individual market. Under ObamaCare, their incentive will be to quit their jobs and head to the exchange.

To add to this burden, the Obama administration has decided hospitals, AIDS clinics and other providers will be able to enroll uninsured patients in the exchange and pay premiums for them in order to get private insurance to pay the bills.

Bottom line: a lot of high-cost patients are about to enroll through the exchanges, causing overall costs for participating plans to be much higher.

Where we are now. After one month, there are signs that insurers got their pricing significantly wrong. Because it is so hard to enroll in the ObamaCare exchanges, only the most persistent (that is, those who expect the highest medical claims) spent hours navigating the website to sign up. According to an HHS report, of those who selected plans from October through December, only one quarter are between the ages of 18 and 34, while one third are between 55 and 64; 55 percent are between the ages of 45 and 54. Priority Health, a Michigan insurer, reported that the average age of new applicants is 51, versus 41 in the previous individual market.

It certainly looks like the adventure will be very expensive. By 2015, the insurers will likely ask the federal government for risk corridor subsidies. The administration has no flexibility in this regard. It would be a mistake to blame the insurance industry, however. It would be unreasonable to expect them to lose money on ObamaCare.

The Democrats’ argument. In its original analysis, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) assumed that the risk corridors would be budget neutral (as noted on pages 10 and 39 of this analysis). More recently, the CBO estimates that the risk corridors could generate a 10 year profit for the federal government of $8 billion — based on the experience of the Part D program. At the hearing, the Democrats seized on this estimate to argue that the risk corridors aren’t going to cost taxpayers a dime. Another witness, Washington and Lee Law School professor Tim Jost, argued that the existence of the risk corridors lowered risk and therefore premiums in the exchange. Lower premiums, in turn, mean less spending on the tax credits that subsidize insurance in the exchanges. But see also the rebuttal testimony by former Bush administration official Doug Badger.

However, the CBO’s estimates were not based on any recent data on who is enrolling. It seems most improbable based on what we know so far that the corridors are going to prove profitable for taxpayers.

The Republicans’ argument. The Republicans are calling the risk corridors a potential bailout of the insurance companies. However, the industry problems are not problems of their own choosing. And it appears things could get worse because of additional extra-legal decisions of the Obama administration, including the most recent potential decision to delay insurance cancellations for another three years:

Extending the ObamaCare exemption could forestall a new wave of policy cancellations just before the 2014 midterm elections. But, like other politically motivated delays and exemptions, such a move could undermine the exchange’s fragile finances.

Aetna said Thursday that it expects to lose money on ObamaCare exchange plans. Earlier in the week Humana (HUM) blamed the president’s 11th-hour “keep your plan” switch for making its exchange plan enrollment older than expected.

Americans who pay less under their old plans than via ObamaCare presumably are in better health, while the exchanges get the older, sicker patients who will save money. An older, sicker risk pool will mean higher costs for insurers. (Investor’s Business Daily)

A better solution. Wharton school health economist Mark Pauly and his colleagues have studied the individual market in great detail and discovered that despite so much negative rhetoric in the public policy arena this is a market that worked and worked reasonably well. Despite President Obama’s repeated reference to insurance plans that cancel your coverage after you get sick, this practice has been illegal for almost 20 years and in most states it was illegal long before that. And despite repeated references to people denied coverage because of a pre-existing condition, estimates are that only 1 percent of the population has this problem persistently. (Remember: only 107,000 people enrolled in the federal government’s pre-existing condition risk pool — out of a population of more than 300 million people!) At most, Pauly puts the pre-existing condition problem at 4% of the population.

So we started with a market that was working and working well for 96 to 99 percent of those who entered it and we have completely destroyed that market — ostensibly to help the few people for whom it did not work. We suspect that after the next election members of both parties will want a major return to normalcy. How can that work?

There is a principle that must never be violated. An insurance pool should never be allowed to dump its high cost patients on another pool. Suppose an individual has been paying premiums to insurer A for many years; then he gets sick and transfers to insurer B. Is it fair to let A put all those premium checks in the bank and force B to pay all the medical bills? Of course not. But even more important, if we do that we will create all of the perverse incentives discussed above — plus many more we might have added had time permitted.

The alternative is something we call “health status insurance.” In the above example, the individual would continue paying the same premium to B that he paid to A and B would pay an additional amount to bring the total premium up to a level that equaled the expected cost of the individual’s medical care.

Compare this idea to the Medicare Advantage market. Enrollees all pay the same premiums, but when a senior enters an MA plan, Medicare makes an additional payment to make the total amount paid reflect the true expected cost the senior brings to the plan. Because of this system, MA plans do not run away from the sick. In fact, there are special needs plans that specialize in attracting enrollees with high costs (about $60,000 per person on average).

Risk adjustment in Medicare does not work perfectly, however, and because the government runs the procedure, political pressures often interfere. So we recommend risk adjustment within the market rather than by an external government bureau. On this approach, insurer A and insurer B would have to agree among themselves on an appropriate transfer price. Only if they could not agree would the problem be left to an insurance commissioner to resolve.

“But higher premiums discourage the healthy and the marginally sick from buying. As more of those decline coverage, the premium must be raised again. We could get a “death spiral,” in which the premiums go so high no one can afford then.”

This is the big fear with Obamacare, is that the healthy aren’t incentivized to purchase costly health insurance. Therefore, the ones purchasing it are the sick, which will cause the idea of Obamacare to crumble.

Not necessarily the idea, but the foundation. It hinges on young, healthy people signing up for the exchanges. If only the sick sign up, which is what could happen, there could be big problems ahead.

“…cities and towns across the country with unfunded health care commitments are readying to dump their retirees on the exchanges, nationalizing the costs.”

This can only worsen the problems that have started due to ObamaCare. These places are willing to dump everyone on to the exchanges, mostly those who have higher health care costs, and this will only increase premiums cost if young people don’t sign up off balance the costs.

“So we started with a market that was working and working well for 96 to 99 percent of those who entered it and we have completely destroyed that market”

Then what was the point for ACA? If the system we had was working completely fine for the vast majority of the population, why was blowing it up and messing it up for everyone an option for healthcare reform?

I think it was more for Obama and his ego to promise change more than it was a need to revamp they healthcare system.

“By the way, did you know that there is a similar risk corridor in the Medicare Part D program . . . ”

Yes, and risk adjustment has also been used for many years by States as part of their small-group rate mechanisms. Connecticut and New York are two that I encountered, back in the day. I think there were (or are) others.

Besides, and as you make quite clear, risk-adjustments do not fully offset unexpected losses. (Neither do tax deductions fully offset the cost of deductible expenses.) In either case, one may choose to believe otherwise – but reality will not be fooled.

The program was designed to help 1 to 4 percent of the population, and destroyed the market entirely. It doesn’t make sense. It would be more reasonable to have kept the system as we used to have it. If the government’s goal was to help that small percentage of the population (there is nothing wrong with having this goal), they should have found ways to help them without harming the remainder. This way we could have provided universal healthcare without compromising the viability of the industry.

Well hindsight is always 20/20…

The pre-ACA high risk pools that operated in 35 states had an average medical cost ratio of 250%-300%. In other words, premiums paid for only 33%-40% of medical claims and the premiums were comparatively expensive for less than stellar coverage. The costs not covered by insurance premiums were paid by a combination of general state tax revenues and surcharges on health insurance policies. Only about 200,000 people actually got health insurance coverage through these plans as compared to the estimated uninsurable population of 4-5 million. It would probably cost $80-$100 billion per year to cover them all.

There are two main problems with high risk pools. First, politicians are generally reluctant to vote to spend so much money for subsidies to cover a tiny percentage of the population many of whom are too sick to even vote. Second, this approach amounts to telling insurance companies that they can cover all the healthy and marginally sick people and earn a respectable profit by doing so while taxpayers will pick up the huge cost of insuring the small percentage of the population that is uninsurable under conventional medical underwriting standards. It doesn’t pass the sell test.

Correction: It doesn’t pass the smell test.

“earn a respectable profit . . . while taxpayers will pick up the huge cost of insuring the small percentage of the population that is uninsurable under conventional medical underwriting standards.”

BC that’s correct. Insurance – or reinsurance – can definitely create moral hazard, although few except people experienced with insurance financing ever seem to believe it.

btw: sell, smell – both work just fine.

It is important to point out the fallacies that Obama included in the promotion of Obamacare. The use of these deceptions helped the legislation to be approved. The President overstated the issues that he wanted and by doing so he destroyed an industry that was working fairly well. As this post highlights, it has been illegal for several years to drop the coverage of those who become sick, but Obama claimed this to be an ongoing problem. If it was, there was no need of a major overhaul in the system; the only thing that the government had to do was enforce the law better. This would have resolved the “big” issue that the President talked about. Also, Obama stated that all of those who had preexisting conditions were not allowed to purchase insurance. This post shows that it was only a small percent of the population who had this issue. Again, this is an issue that might have been solved without a major overhaul of the industry. It is clear; President Obama wanted a reform in the health care sector. He wanted to change how the industry operated and to accomplish his goal, he overstated some issues with the sole intention of proving his goal.

This is what happens when we have a narcissistic President that wants to be under the spotlight. It shows that presidents would do whatever they need to in order to leave a legacy. Sometimes they focus on the grandeur of their actions rather than in their effectiveness.

As one of my American government professors said during the 2008 election, Obama had been given “the gift.” It is the same gift that FDR and Lincoln had been given. They entered the country while it was in turmoil and brought us back to our feet. If Obama had able to do that he could be mentioned in the same breath as them. Except, as evident now, he squandered his opportunity and could leave us worse off.

I still have my doubts about the risk corridors. If the government is going to have to “bail out” the insurance companies, the risk corridors is a concerning matter. If on the other hand the government is going to make a profit from them, it is even worse. Why do consumers have to over pay for the government to get extra money? I think that there are problems with these risk corridors, and I believe they should not be in place. I will wait until there is some data available about these, but until I am convinced that they are not harmful, I will oppose them.

Neither party convinces me with their arguments. Isn’t there an alternative down the middle with a solution that actually works?

With two parties who are not willing to compromise at all? This is doubtful.

Excellent post. I like your “better solution.”

Thanks for the recognition, John. I have a large number of my Hoover monograph books in my garage.

Hey, thanks for the great article! I was a little confused with the risk adjustment market concept. I gather that you are advocating that we expand risk adjustment to include firms not participating in the exchange so that firms cannot dump high cost employees into the exchange. Then we get to the Detroit question. If Detroit dumps its employees into the exchange,who is going to pay Detroit’s risk adjustment?

If and when Detroit dumps its retirees onto the exchanges, then the federal tax burden will eventually rise by a relatively small amount to pay subsidies of all kinds.

If Detroit were to keep its retiree health program, then the tax burden on the poor souls who still live in Detroit would rise, and by a lot.

This transfer of bad risks and over-generous union benefits to the federal government is not a pretty process. But we have done it for 30 years with the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp and it has not killed us.

Personally, I would replace most of the ACA with an expansion of Medicare down to age 60 or 55, with some of the cost paid by the taxpayers and employers who would benefit.

Bob,

PBGC benefits are capped at, I believe, $4,500 per month ($54,000 per year) and that’s for one life for a 65 year old or older retiree. There is a benefit haircut for each year short of 65 that the pensioner is. So, better paid employees like senior airline pilots, middle and upper middle managers and folks who are well short of 65 could get significantly less from the PBGC if their employer goes bankrupt than they would have received from their defined benefit pension plan if their company remained a going concern.

Moreover, unionized employees of companies like Bethlehem Steel that went broke in the early 2000’s lost their retiree health insurance altogether. So, while the PBGC does provide an important backstop to employer defined benefit pension plans for which those companies pay a per employee premium into the PBGC each year, it’s far from a complete backstop.

As a taxpayer, I would strongly object to completely protecting the gold plated pension and health insurance benefits that were awarded by irresponsible managements that gave the store away to unions to buy labor peace. This is exactly what’s happened throughout much of the state and local government sector. At the federal level, by contrast, unions cannot bargain over wages and benefits. They can only file grievances related to working conditions, promotions, discipline, etc.

The ACA exchanges are not all that generous to early retirees.

Picture a retiree from the city of Detroit who is 62 years old, and between his pension and Social Security has an income of $45,000 a year.

Today he gets a health policy from his employer, for he pays maybe nothing and maybe $250 a month.

Sending him to the ACA exchanges will force him to buy a policy without subsidies for at least $400 a month, and that is for a high deductible option.

What I am trying to say is that being dumped onto the exchanges saves money for the city of Detroit, but it is no lavish bailout for the persons involved.

Bob,

I don’t have a problem with either private companies or state and local governments ending health insurance coverage for their retirees and send them to the exchanges instead. The retirees will pay more for less coverage but not more than 9.5% of income if their total income is below the subsidy threshold. State and local governments, by contrast, will save a lot of money that would otherwise have to be covered through a combination of higher taxes and continued crowding out of other important spending priorities like education and infrastructure. The downside is that it could overload the exchanges will older people well beyond what was contemplated when the ACA became law.

My former employer, a Fortune 500 company, did not provide retiree health insurance to its non-union employees. It used to let us buy into the company’s plan with our own money which allowed us to access a decent plan at group rates. At the end of 2011, that ended. I had to pick up coverage under COBRA for my wife until she became eligible for Medicare. For a number of old line companies, including the one I worked for, there are many more retirees than active workers. That means that for those companies, the cost of health insurance for retirees far exceeds what it pays to cover the active workforce. It’s a big legacy cost that hurts their competitive position vs. younger companies, including foreign auto manufacturers that built plants in the U.S. in relatively recent years. Shedding those retiree healthcare costs will help level the playing field.

For state and local government, it would make their overall financial condition more sustainable over the long term even if they have to sweeten pension benefits as a partial offset. There is no equivalent of the PBGC in the public sector by the way when it comes to pensions which makes the saga of Detroit’s bankruptcy potentially groundbreaking depending on how it plays out.

Once again, its good to remember that the cost of our nation’s healthcare industry is at least 25% more per citizen than any other of the 43 developed nations of the world. For 2010 alone, the difference amounted to $650 Billion for that year. Of this amount, 29% was paid by the Federal government and 16% by state and local government. As such, the excess cost was the largest single component to the national debt that year. What is most important to keep in mind, is, that nothing in our nation’s approach to healthcare reform will improve either its efficiency or effectiveness. Unfortunately, the ACA 2010 is likely to add another $100 Billion to the cost of our nation’s healthcare…further increasing its contribution to our annual national debt. No matter how you decide to spend the $$$, we still need a supremely focused strategy to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of our nation’s healthcare. Yes, I know, I’ve said it before. But, I still believe that our nation’s discussion about ACA 2010 ignores the true elephant in the closet: we would need to reduce our nation’s maternal mortality ratio by 80% to rank among the 10 best of the world’s 43 developed nations. To become more efficient, it will first have to become much more effective – community by community.

Our healthcare cost problem is not inefficiency or even too much utilization. It’s high prices per service, test, procedure, drug and medical device. We need to move away from the fee for service payment model in favor of bundled payments for surgical procedures and capitation for primary care and disease management.

We also need more countervailing power on the commercial payer side to counteract large hospital systems that currently have too much market power. I think we will see tiered and narrow insurance networks continue to gain traction along with higher deductible health plans. Over time, insurers will also make more use of reference pricing in areas that lend themselves to the concept. Employers are also likely to use private exchanges, especially for retirees, in order to both cap their financial exposure through a defined contribution as opposed to a defined benefit model and to allow individual retirees and, eventually active employees as well to choose an insurance plan that best meets their needs. Drug prices in the U.S. are probably higher than they need to be for the industry to earn a sufficient return on capital to encourage research, investment and risk taking.

With respect to infant mortality, the poorer statistics in the U.S. are mainly a function of the greater incidence of poverty vs. other developed countries and have little or nothing to do with the healthcare system itself.

I was referring to maternal mortality ratios among the 43 developed nations of the world. The last report from the UNICEF/WHO/WORLD BANK reviewed the maternal mortality ratios of the developed nations from 1990 thru 2010 (accessible through the World Health Organization web site). The top 10 nations have maternal mortality ratios (MMR) of 3-5 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010. The report also reveals that the 43 developed nations had a combined MMR of 26 in 1990 and 16 in 2010. For the United States, it was 12 in 1990 and 21 in 2010 ( Yes, it worsened! ). As noted above, our nation’s maternal morality would need to be reduced by 80% to rank in the top 10 developed nation’s of the World. As reported by the AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL USA Report of 2010, the improvement in maternal mortality for our nation will not occur until there is available and accessible Primary Health Care for all citizens. Teaching each family member about accessible healthcare would benefit all citizens, but especially women who are or may become pregnant. This tradition for our nation does not exist for each citizen to the level necessary for any rapidly evolving health complication, especially when occurring during a pregnancy: minutes are crucial rather than hours.

Timely intervention in potentially catastrophic illnesses is also the best means to reduce the ultimate cost of these illnesses. For instance, if you arrive in a hospital with chest pain from a heart attack, the ER has 30 minutes to make the correct diagnosis and to administer a clot buster medication to you. Every hospital monitors their performance to this standard. Assuming it worked, you would be out of the hospital after two days and would have had a heart catheterization to check out all the arteries in your heart. Lest anyone think that a maternal mortality ratio of 3-4 might be difficult to achieve in the United States, four states already achieved this GOAL in 2006: Vermont, Maine, Indiana and ALASKA.

Paul Nelson, thanks for naming the states that have achieved the target rate for maternal mortality.

Do you also know which states have the highest rates of maternal mortality?

Do you happen to have the same info on infant mortality?

Best of all, could you just supply a link to the source you are suing for this info?

Many thanks.

For 2001-2006: Louisiana 17.9, Maryland 18.7, New York 18.9, Mississippi 19.0, Alabama 20.9, Oklahoma 20.1, Georgia 20.9 and Michigan 21.0 .

Two notes: 1) the District of Columbia is above 30.0 and 2) the data sets for any year since 2006 are not accessible. The CDC does not release this data as a result of “confidentiality agreements with the States.” I have been unable to locate the legal basis for these “Agreements.” The only other data set is for 1987-1996. Another story for discussion. These two data sets have unusually close relationships with longevity, an indication that state by state maternal mortality ratios are the best measure of State by State healthcare accessibility (unpublished analysis, so far!).

Sorry: sources are 1) MMWWR: 9-4-98 / 47(34); 705-7 Maternal Mortality — United States, 1982-1996 and 2) National Women’s Law Center at http://hrc.nwlc.org/status-indicators/maternal-mortality-rate-100000 (Note: This Page is sometimes hard to locate, for reasons I also don’t understand.)

The CIA fact book has a table that shows maternal mortality rates by country. The U.S. rate was indeed 21 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2010 which placed the U.S. at 137th lowest out of 184 countries listed. The lowest rate was 2.0 in Estonia and the 2nd lowest was 3.0 in Greece. I’m not sure how to interpret the data. Would you really prefer to get your healthcare in Estonia or Greece? I wouldn’t.

One contributing factor to material mortality is complications from abortion. While abortions have declined in the U.S. in recent years, we still do about 700,000-800,000 of them per year. Another contributor is poverty. Out of 4 million births in the U.S. each year, over 40% are paid for by Medicaid. I don’t think this data tells us much, if anything, about the overall quality of healthcare systems in various countries.

It we don’t offer accessible healthcare to each citizen, aka EMTALA, is there any realistically economic means for improved efficiency other that rationing? The issue is that the ultimate cost for any person’s healthcare cannot be anticipated from day to day. We all know that 10% use 70% of the nation’s healthcare cost. And, the 10% group changes from year to year. Any opportunity to control these costs must be managed in advance. The triage process involved must apply to everyone, especially for women during a pregnancy.

The military has the most experience with managing triage. Over the last 150 years, the death rate associated with armed conflict since the Civil war has changed from over 50% to less than 10% even though the lethality of the injuries is much worse). How this was managed in Iraq is nothing short of amazing: transport to a waiting mobile surgical suite within twenty minutes to Germany in less that 48 hours. Our civilian healthcare has lots to learn all the way from our trauma centers to day to day Primary Health Care. All this is known. What is lacking is our “collective will” to make it happen! No amount of financial tinkering will make a difference. There, I said it. Correct me if I am way off base. Oh, and be sure to explain why Maryland, Michigan and New York have such bad maternal mortality ratios even though Alaska was one the best!

“Oh, and be sure to explain why Maryland, Michigan and New York have such bad maternal mortality ratios even though Alaska was one the best!”

Paul, you make a good point. It’s necessary to understand the factors that drive outcomes variability because otherwise the variability continues – and high-outlier states remain unlikely to learn how to produce results more like the low-outlier states. John Wennberg and others pioneered this kind of research more than 30 years ago – and Wennberg discovered unacceptable variability in many more places than maternal mortality. Policy-makers should be paying attention.

It seems clear the explanation cannot simply be that the US health care system has failed; I think the state-by-state variability in outcomes suggests it’s more accurate to say there is in fact no “US health care system”. A better explanation is surely that a variety of other factors among the states drive the strikingly variable outcomes results. I think those factors would be the deeper problems that must be addressed. So why have our leaders not brought that message to the public?

It seems equally clear that insurance mechanisms cannot be expected to rationalize state-by-state medical outcomes variability – any more than they can control high medical delivery costs. That’s why I think high insurance costs are symptoms of deeper problems – but they are not the problems. It’s usually an error to mistake the symptom for the disease.

What’s perhaps worse is that our politicians and so-called thought leaders have done such a miserable job of educating the public on the nature of the deeper problems. Public attention is instead focused on symptoms not the disease; the public is told a cure is at hand when it is not; and meanwhile the problems persist, and worsen.

Well said!

The reality is that the insurers got in bed with the devil and they will burn when we either move to a single payor system (Dems next move) or we move to a competitive free market (Reps next move). Sorry, Aetna, United, Cigna, Humana, and BCBSs….as Marx predicted, you sold them the rope to hang you by.

If a good or service is rendered, for money, somebody has to pay. This is an inescapable truth…

Most likely you are a enthusiast of World of Tanks, today is the launch of the Planet of Tanks Hack

2.2 with which you will make your match a lot more fascinating and fascinating.

As we know the objective of this match is battling amongst

two players which controls a tanks. Many thanks to our programmer

who labored tough to make World of Tanks hack two.two with all these characteristics and effortless use.

With this Entire world of Tanks hack you can include endless quantities of Gold,

Credits and Encounter, but if you want you use our wonderful features of wallhack and speedhack and also premium

extender. This hack will make your gameplay 10x less difficult and will make you

reward from all the premium functions this kind of as fifty% a

lot more credits and fifty% a lot more encounter

per struggle, and a clean garage. That’s right!

All these features in 1 software! What are you waiting around for

? Seize this instrument and equipment yourself up for enormous battles!

My homepage: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GzibrXbuHy0

Regarding Paul Nelson’s statistics on infant mortality:

if there are 21 deaths per 100,000 live births in the US, and if the US has about 4 million births a year, that would mean about 840 infant deaths a year in total.

Let’s assume for the sake of discussion that half of those infant deaths occurred out of medical chance tragically for well cared for and well insured mothers.

We are then left with 420 preventable deaths.

Are we going to judge our $3 trillion health system on 420 deaths?

I have always been skeptical about measuring health systems based on mortality.

But I never knew how skeptical!!

A mixed metaphor I believe!

The WHO mortality data is taken without alteration from each country, whether or not they have a good or bad system in place to collect data. In addition, they do not normalize the data in any way. For example, in the US we count as live births many that are consider still born in other countries so that they are not births and then deaths as would be reported in US numbers. If the US number are getting worse over time, it is not because of poorer care or ill treatment of the newborn, but rather a recognition that we are treating lower and lower birth weight babies to save them ( many from drug and alcoholic parents who have infected the fetuses with their addition)

These considerations are well taken, but we are talking about maternal mortality and not infant mortality. In fact, our nation’s infant mortality continues to go down and not up. As for maternal mortality, there has always been professional commentary about discrepancies among the world’s nations for the level of precision represented by the data. In fact, the last report from UNESCO-WHO-World Bank actually made estimates of these factors. As a recent student of maternal mortality, I must also say that there is very little true evidence for this among the 43 developed nations of the world or from state to state, nationally.

The over-riding issue for out nation’s maternal mortality IS: why was it necessary for the CDC to with-hold this data from public transparency beginning in 2007 to the present? Was it sandwiched into the Congressional ban on any epidemiologic studies by the CDC of trends regarding instances of mass violence…beginning in 2007? If so, what a very sad commentary about the character of our Federal government.

I would personally not want to intimate that viewpoint to their extended families. Within my own extended family, a father became a single parent for 2 teenage children when his wife died from a sudden unexpected illness. It is devastating. The real issue of course is that the priorities do not exist to even think about the options available for achieving what is clearly a solvable problem, as it is for Maine, Vermont, Indiana and Alaska. In addition, what are the costs to our society for any remaining children who do not have their mother from a pregnancy related death?

Based on the comments above:

Medicaid covers about 40% of the nation’s births.

That means 1.6 million births, and if the average vaginal delivery costs $9,000 then we are spending

$15 billion on this item. Add extra $ for problem births and we are spending $20 billion.

For this large expense, we are holding mortality down by maybe 300 mothers and 200 infants.

Now I have no problem with the $20 billion. Children are precious, and we blow through $20 billion on Pentagon waste every single week.

What baffles me is why we use mortality to justify this expense. Is this because it is such a dramatic statistic?