Stunning Results from California

I’m going to summarize in a single paragraph a debate that has been raging in health policy for the past two decades.

On one side is what I call the health policy orthodoxy. On my side is a small group of people that believe markets can work.

The debate goes like this. Them: The marketplace can’t work in health care. Patients don’t have enough knowledge; there is unequal bargaining power; and medicine is a profession, not a business. Us: What about cosmetic surgery? Them: That’s an exception. Us: What about Lasik surgery? Them: That’s another exception. Us: What about medical tourism? Them: That’s only for rich people. Us: What about Health Savings Accounts? Them: That’s only for healthy people. Us: What about walk-in clinics? Them: Okay, maybe the market can work for small stuff, like flu shots, but it can’t work for expensive procedures, like joint replacements and heart surgery.

Do you know how many man hours have been spent repeating these sentences at conferences, briefings and hearings and in editorials and journal articles? Don’t ask.

On the last point (about expensive procedures), I think the other side has had the better argument. Until now.

In my book Priceless I made a bold claim. I predicted that most employers could cut the cost of hospital care in half by an aggressive version of “value-based purchasing,” also called “reference pricing.” I also predicted (again, without any evidence) that if a significant number of patients were involved, the hospital market would begin to resemble a competitive market.

Here’s how it works. Employers pick out a few low-cost, high-quality facilities and agree to pay all or most of the cost of the procedures at these facilities. Employees are free to patronize other providers, but they have to pay the full amount of any extra expense.

A recent example is Wal-Mart, which has selected seven centers of excellence for elective surgery. Employees can go to other providers, but they may face out-of-pocket charges of $5,000 or $6,000. Lowe’s has a similar arrangement with the Cleveland clinic for cardiac surgery. This is what we call “domestic medical tourism” at the NCPA. I like it. But it’s not the only approach.

Safeway, the national grocery store chain, has established a reference price for 451 laboratory tests ― set at about the 60th percentile (60 percent of the facilities charge this price or less). If the employees choose a more expensive facility, they must pay the extra cost out of their own pocket.

Lab tests are relatively inexpensive, however. How well would reference pricing work for big ticket items? WellPoint, operating in California as Anthem Blue Cross, started with joint replacements and the results are fascinating. They are planning to extend the approach to as many as 900 additional procedures, beginning next year.

Like other third-party payers, WellPoint discovered that the charges for hip and knee replacements in California were all over the map, ranging from $15,000 to $110,000. Yet there were 46 hospitals that routinely averaged $30,000 or less. So WellPoint entered an agreement with CalPERS (the health plan for California state employees, retirees and their families) to pay for these procedures in a different way.

WellPoint created a network (I am informed that this is not technically a “network” but I’m going to call it that anyway) consisting of the 46 facilities. There was no special negotiation with these hospitals, however. WellPoint simply encouraged their enrollees to go to there. Patients were free to go to elsewhere, but they were told in advance that WellPoint would pay no more than $30,000 for a joint replacement outside the network. (At all the hospitals, patients pay a 20% copayment up to $3,000.)

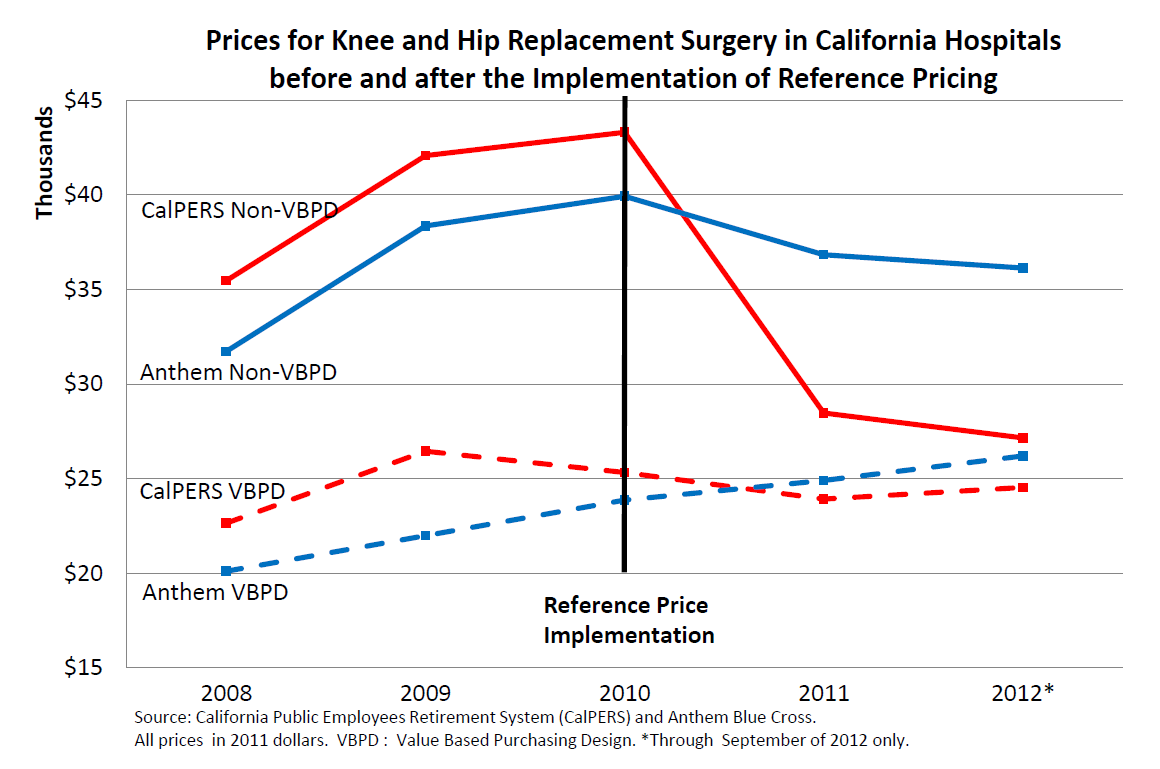

Take a look at the graph below. The patients in this graph have been adjusted for case severity and geographical diversity in a study by Berkeley health economist James Robinson and his colleague Timothy Brown. The bottom two lines show patients who went to the 46 hospitals. The red line reflects the average cost for CalPERS patients who, beginning in 2010, were enrolled in WellPoint’s new program. The blue line is the control group. As the figure shows, there is not that much difference between the two populations in terms of the cost of their procedures.

Now look at the top two lines. The red line represents the average cost for CalPERS patients who went outside the network (about 30% of the total). Beginning in 2010, they undoubtedly told the providers they had only $30,000 to spend. As the figure shows, the cost of care at these hospitals was cut by one-third in the first year and continued heading toward the average “network” price over the next two years.

This is dramatic evidence that when patients are responsible for the marginal cost of their care (and therefore, providers have to compete on price) health care markets become competitive very quickly. Remember, the insurer is not bargaining with these out-of-network providers. The patients are.

Look at the uppermost blue line. These are (control group) patients who are not telling providers they have only $30,000 to spend. Nonetheless, their price/cost of care begins declining in 2010 as well. This is exactly what would happen in the market for canned corn or for loaves of bread. People who comparison shop affect the price paid by those who don’t.

Now ask yourself this very important question: Who is more powerful at controlling health care costs? Huge third-party bureaucracies negotiating with providers? Or patients paying the marginal cost of their care?

Game. Set. Match.

Postscripts

- There is a public policy issue here. Wherever I look, I find there are people in the private sector who are light years ahead of the government. Not everybody in the private sector, of course. But there is certainly no reason for the government to be spending millions of dollars on pilot programs and demonstration projects. The interesting innovations are already being done privately. Almost everything the government is doing is pointless waste.

- Uwe Reinhardt had a post on reference pricing the other day. However, in his telling of the story, the focal point is the third-party payer, who is seen as the main actor ― pushing (nudging?) patients to make lower cost choices. This is a very common point of view, but it misses what is most important. In California, the third-party payer set the market in motion, but then became less and less important through time. Actual prices were then determined by the interaction of thousands of individual patients and providers.

- Whereas reference pricing is often portrayed as a burden for patients, done correctly it liberates them. This would be ever so much clearer if all the patients had a generously funded Health Saving Account.

- WellPoint’s own analysis shows that the quality of care at the 46 hospitals is as good as or better than in out-of-network hospitals. But in the future that might change. We know that when providers compete on price they also tend to compete on quality. And it is here that the HSA is really important. Providers are more likely to compete on quality if patients have the funds on hand to pay more if higher quality costs more.

Finally, I hope no one will conclude that these developments are the result of the Affordable Care Act. If anything, the ACA is actually an obstacle to sensible reform. Some health plans have been reluctant to try out reference pricing for fear the Obama administration will find it in violation of the out-of-pocket restrictions imposed by ObamaCare. (See this discussion by Jamie Robinson and Kimberly MacPherson.)

Great post.

This is where MediBid just cuts right through all of the opacity and restores transparency and competition. That’s why we get rates that are one half of what insurance companies get.

“Here’s how it works. Employers pick out a few low-cost, high-quality facilities and agree to pay all or most of the cost of the procedures at these facilities. Employees are free to patronize other providers, but they have to pay the full amount of any extra expense.”

-This is a GREAT idea. I hope it catches on.

I agree! We need more ideas like this one!

My dear friend John:

Aren’t we splitting hair here?

With the backing of Calpers, the insurer — yes, third party payer — Wellpoint and certain providers hashed out the references prices for hip and knee replacement.

Given those prices, patients then reacted to them. To my knowledge, patients did not haggle with hospitals over those prices. They simply reacted to prices the insurer had negotiated for them.

That other providers then followed suit and lowered their prices – as drug companies did in Germany’s reference pricing – can be attributed to both parties: insurers and the patients’ reactions to the prices set by the insurer.

I believe my post was pretty clear on the role of patients in this game, when I described it in the abstract.

Uwe

Best,

Uwe

Uwe:

We are not splitting hairs and you are still getting it wrong. All WellPoint did was say, “If you want to go out of network, we’ll give you $30,000 (minus the co-payment) and that’s that.”

What was actually paid was determined by the interaction of the patients and the hospitals, and not by any negotiations by WellPoint.

In other words, WellPoint indirectly created a real market for joint replacements in California. It is remarkable how quickly the market began to function like a real market, in which providers compete on price.

“If anything, the ACA is actually an obstacle to sensible reform.”

We all know that the ACA was not designed to be the answer to all aspects of the health care industry, nor does it stop all innovation. It merely addresses some of the problems that the free market won’t.

Also, isn’t Medicare implementing the same strategy of setting a price-point for procedures to any physician who wants the business? The only exception is that the difference between what the doctor wants and what the patient can be charged doesn’t exist in Medicare. I understand that the ability to retrieve that cost difference makes physician’s bottom line more palatable, but wouldn’t the practice only benefit those patients who could afford it?

How do you know what WellPoint or CalPERS communicated to the employees? I have seen nothing on how the employees knew of those facilities, why their surgeon used those facilities and most of all what would the price have been otherwise. Employee’s do not just get up one morning and drive to a particular hospital and go to the front desk and ask for joint replacement for $30,000. There has to be much more to this story. In fact, there is an element of possible increase in either the mean or the average. It could be that the costs rose in direct proportion to the amount available for payment and this is not true free market pricing or reference pricing.

But the third party as pushing/guiding/arranger (i.e., the insurers and their affiliated networks) are totally unnecessary if you just require transparent, non-discriminatory pricing by providers. All payer will bring about the market based competition (with its affiliated patient resource services that will develop to help do the information processing and guiding) and innovation in both insurance and provider pricing products that will achieve fair and consistent pricing without the rent seeking illegitimate advantages of the BUCAHs – they are the enemy, along with the government which policies they are simply trying to replicate on their slightly smaller scale. The vested interests must be stripped of their artificially contrived power.

Excellent news!

In my approach there is a mandatory HSA (HFA), funded from wage deductions, and It can only be used to pay at the 50th percentile in the neighborhood of the provider.

The safety net Basic Minimum Policy pays at the 10th percentile.

Note that this study also addresses the common objection to market solutions that in an emergency the patient is in no position to go to the least expensive provider. … The market adjusts so that all providers, at least almost all providers, offer prices substantially in agreement.

Of course there will always be Mercedes-Benz and Ferrari.

And of course many expensive procedures such as those discussed in your post, are not an emergency

John this is a valuable article and I would add only a small suggestion that stimulating hospital and professional competition on price, while clearly necessary, may not be enough.

To the extent there is “air” in present pricing, price competition will tend to let it out – as you demonstrate. But physicians argue that there are real costs that they bear today, that result from inefficiencies in the delivery system they have no direct control over; I assume the same is true for hospitals. These costs must eventually be wrung out, too. They are part of medical pricing today and, because they are real costs, it may take more than price negotiation to eliminate them.

“If anything, the ACA is actually an obstacle to sensible reform.”

Yes – and mainly, I believe, because it is principally an insurance mechanism that does virtually nothing to promote meaningful, practical reforms of the medical delivery system.

John, I agree. it would be helpful if we could get rid of the Stark Amendments, which even Pete Stark now favors.

Take a look at the Surgery Center of Oklahoma City. Prices are posted on-line, the center is extremely successful.

Ken, you are a model for us all.

I think so too.

This is encouraging.

I would point everyone to HB2014 from Arizona– will become law on Jan 1, 2014…

All providers and hospitals must make their direct pay (cash) price available for the most common services they provide…

1. no government price setting or reporting (explicitly prohibited)

2. no discrimination based upon insurance status (price must be same for insured and uninsured) (medicare pts out of luck)

3. no reporting/ filing insurance requirement for providers/ hospitals if direct pay price paid

I agree that reference pricing is just another layer of third party price fixing… but, it is simply a ‘defined contribution’ hc plan vs. the defined benefit plan that exists almost everywhere today… so, while new to hc, it has been a part of employee benefits ever since IRA and 401k plans were created…

The aca and 3rd party payer model prevents the market from driving change

Through medibid we get pricing for hip replacement in ca of $14, 450

Hi John,

Obviously free market pricing will bring down health care costs. But what if prices were set with reference to real costs? The problem is virtually no one in health care sets their prices based on their costs. Your article still describes a market in which prices are set by what the traffic will bear. And notably, the price pressure you describe is exerted by big companies battling big institutions with the patient being the pawn in the middle. Shouldn’t the patient have some say, particularly about quality and factors not related to cost?

So while the jockeying of big institutions demonstrates that health care prices can be negotiated, the power to do so is still not in the hands of consumers, as it is in virtually all other sectors of the economy. In the end, it is the patients’ lives and health at stake.

That is why I am spending much of my time and resources organizing patients, who, in alliance, with their doctors drive utilization, and therefore should drive costs. Health care can only be reformed from the grass roots up, not the top down.

Cheers,

Charlie Bond

You bring up two excellent points:

1. Patent responsibility for first dollar coverage makes them more prudent purchasers of their health care services.

2. Major, full-service health care institutions lose millions in revenue when physicians direct their less ill patients out to specialty clinics and laboratories for procedures and evaluations, where often the most profits are generated. If recaptured, the larger institutions could use the increased revenue to decrease costs for all services across the board.

I would say, in response to Professor Reinhardt, that there are few markets in an industrialized economy where customers actually have to “haggle” in order to discover prices. Sophisticated marketing functions have replaced this expensive friction. If we search EconLit for “posted-price selling” we find a lot of articles explaining its benefits and how it arose historically.

I think the next step for CALPERS, for example, would be to say to its beneficiaries: “OK, we managed to cut costs so much by reference pricing this procedure to $30,000. Now, we take it a step farther. If you can get the surgery for less than $30,000, we will split the difference with you. That is, if the claim comes in at $26,000, you’ll get a bonus of $2,000 in your next pay or pension check.”

That would really demonstrate that it is the patient, not the 3rd-party payer, who is getting costs down.

There is a problem with price disclosure.

Essentially the FTC/DOJ has decided that, when two gas stations across the street from each other post their current prices, that is competition. And when two physicians across the street from each other post their current prices, that is collusion.

The 1996 Joint Policy Statements by the FTC/DOJ are still in effect and were referred to extensively in their joint Statement of Antitrust Enforcement Policy Regarding Accountable Care Organizations issued October 28,2011. The following is from section 6 of the 1996 statement.

http://www.ftc.gov/bc/healthcare/industryguide/policy/statement6.htm

“A. Antitrust Safety Zone: Exchanges Of Price And Cost Information Among Providers That Will Not Be Challenged, Absent Extraordinary Circumstances, By The Agencies

The Agencies will not challenge, absent extraordinary circumstances, provider participation in written surveys of (a) prices for health care services,(15) or (b) wages, salaries, or benefits of health care personnel, if the following conditions are satisfied:

(1) the survey is managed by a third-party (e.g., a purchaser, government agency, health care consultant, academic institution, or trade association);

(2) the information provided by survey participants is based on data more than 3 months old; and

(3) there are at least five providers reporting data upon which each disseminated statistic is based, no individual provider’s data represents more than 25 percent on a weighted basis of that statistic, and any information disseminated is sufficiently aggregated such that it would not allow recipients to identify the prices charged or compensation paid by any particular provider.”

I am the president and CEO of the largest IPA in Dallas/Fort Worth. We have 1500 actively practicing physician members in 50 different specialties. We contract with the five major health plans and many minor ones in the DFW area, a market of 6.5 million people.

I can easily lay my hands on what prices are being paid for almost every CPT code and what prices our individual physician members are accepting for those services throughout the Metroplex. But all of this remains hidden to the consumer (and to our members, I hasten to add). Absent a state law forcing price disclosure, we would not risk it. And the health plans consider their prices to be proprietary.

I’m no economist but I don’t think you can have a market without price disclosure and liquidity.

Our IPA actually operates a secure online market; a tool which our physicians use to contract to sell their services to health plans. It’s cloud-based and continuously in operation since 2001.

Let me know and I’ll give you a tour sometime, we’re just down the road.

Bruce L.

I accept that health plans’ contracts require confidentiality. (Although my EOBs tell me how mych the provider got paid after the claim was adjudicated.)

But I really struggle with Dr. Landes’ interpretation of he DOJ/FTC antitrust guidance as preventing posting prices. Are there cases that demonstrate this? If so, wouldn’t somebody have taken the Surgery Center of Oklahoma to DOJ/FTC by now?

Posting prices is not the same as participating in a survey. The guidance has do to with hospitals sharing the prices they pay for devices, or (now that they’re rolling up physicians’ practices) how much they pay doctors.

I don’t see anything there that prevents providers from posting prices to patients.

Hi John.

I agree with you, the FTC/DOJ have no argument with a single entity or financially integrated joint venture posting prices. I’m sorry if you thought I said otherwise.

They have a problem with price disclosure among competitors.

The distinction is clear in this footnote to Statement 5:

This statement addresses only providers’ collective activities. As a general proposition, providers acting individually may provide any information to any purchaser without incurring liability under federal antitrust law. This statement also does not address the collective provision of information through an integrated joint venture or the exchange of information that necessarily occurs among providers involved in legitimate joint venture activities. Those activities generally do not raise antitrust concerns.

In my example of two competing gas stations posting their prices, you can bet that they will have very similar prices. You and I look at that and see competition. The FTC can look at that and see collusion. And the burden of proof is on the gas station owners to prove that they did not conspire to fix the prices

Honestly, if those two gas stations were on a deserted stretch of highway, I might begin to suspect something was amiss, rather than assuming competition was the reason that the prices were the same.

My organization has about 85 orthopaedic surgeons as members. The largest group is 16 surgeons. There are 57 competing entities. If I were to call them up and ask them each for a cash price for an elective knee replacement (professional fee only) then there would be a range of 57 prices given. If I were to post their prices to the public, in a way that the surgeons could also see them, then soon the prices would have a narrower range than I was first given.

I would say, that’s competition.

I’m afraid the FTC would say to me, “You violated condition 3, “any information disseminated is sufficiently aggregated such that it would not allow recipients to identify the prices charged or compensation paid by any particular provider”, and the fact that the low bidders have moved up their prices shows that this was a collusion to raise prices. Now hire very expensive attorneys to prove to the FTC’s satisfaction that you did not collude to raise prices.”

I was just presenting a threat, which the FTC poses to pro-competitive price disclosure, that others not in my position might not be aware of.

BTW, not to be argumentative but Statement 6, to which I linked, does not mention hospitals (other Statements do,) and joint purchasing arrangements by hospitals is the subject of Statement 7.

http://www.ftc.gov/bc/healthcare/industryguide/policy/statement7.htm

Thanks for reading my post. I hope that this clarifies my point.

This is the most absurd reading or interpretation that I could imagine. I suggest that you let someone read and interpret these things such as Statements 5, 6 and 7 for you.

Hi George,

Please note the signature line on this document, mine as well as our attorney’s.

http://www.ftc.gov/os/2003/06/swphagreement.pdf

When was the last time I spoke with an attorney about legal issues that might pique the interest of the FTC? Literally yesterday, August 8.

Absurd interpretation? Yes, I agree. But no more absurd than the stance I’ve seen the FTC take over the years on individual cases. The complaint against us was boilerplate, not related to our conduct or the facts. I can show you the same words used against similar organizations in vastly different circumstances.

Does the news lately suggest to you that any agency of the federal government has become less “absurd”, more competent, or understands the unintended consequences of its actions better than it used to?

When the FTC is hunting scalps, they don’t really care if you’re a good indian or a bad indian. And they are not shy about their interpretation of the law or their own policy.

Read it to me? I’ve got hundreds of thousands of dollars in canceled checks that I personally signed, paid to antitrust attorneys over the years to “read it to me”. Those 1996 Statements still form the core of the FTC opinions and actions as I mentioned in my first post. I think I have more than a casual understanding of not only the language but, more importantly, how the FTC has used that language over the last decade.

Respectfully,

Bruce L.

Thank you for clarifying. I’m gong to move away from hypothetical DOJ/FTC actions against your group and towards (what I believe are) the economics of pricing commodities versus professional services.

I would actually be quite surprised to see posted prices for physicians like we see for gas stations – in the general sense. Lawyers, management consultants, and periodontists are all generally paid directly by customers and yet they do not post prices like we see at a gas station or grocery store.

On the other hand, if I go to a lawyer, management consultant, or periodontist for a consultation, I can usually get the fee sorted out without too much difficulty, before I agree to buy the service. With physicians who are usually paid by insurers, this is usually impossible.

(Although too detailed for a blog comment, there is also an economic reason why the lawyer and management consultant will usually charge an hourly rate, while the periodontist will charge fee for service. But there is no iron law. Lawyers also charge retainers, and I’ve read lately that in-house counsel at corporations are negotiating fee for service with outside counsel.)

John, this is a most important topic, and it does bring out the “field theory” problems that cause even intelligent people to cling to concepts that have been shown not to be valid long ago. Uwe does not seem to grock that few insurers bother to look at individual procedure prices, as most medical centers have charge masters with tens of thousands of diagnoses and procedures. Instead, negotiations are on the annual rates of increase of that list of prices. Nor is much attention paid to the different dynamics of elective/schedulable procedures and medical admissions where the probable cost of the procedure is not knowable in advance.

By focusing on individual procedures, and achieving what appear to be real reductions in prices, the uncovered costs are simply absorbed by those other services via cost-shifting. It is true that costs are not revealed by pricing.

We once had pricing by room size, and now we think that is primitive. It is. But so is pricing by procedure. Here is why:

The whole institution is engaged in providing a service, not just the surgical team that does the procedure. The lab, the OR, the central sterile supply gang, the security office, the legal staff, finance, logistics, internal education, biomedical engineering, and dozens of other functions. To give one surgical procedure, all these things must be in place and operating. Like a train that needs rails, signals and dispatch jut to take one person on a trip. One cannot really shrink and expand directly in relation to volumes. So a provider is guessing when it plans for, for example, an orthopedic surgical suite and associated beds that will be devoted to joint repair. Prices are determined by estimating future demand, dividing that into total costs and adding a percentage representing overhead–all those other functions. To have prices cut, means that other clinical programs must pick up the difference–usually non-surgical programs. What happens when a lower price brings additional business over the forecast amount is that queues develop–waiting lists, which are one hallmark of a “planned” (non-market) system. In fact, Canada deliberately limits the number of procedures of various kinds to set up waiting lists to allocate its budgets with providers. This is why you either have a market-based health system or you have creeping government controls. Some mystical half-way measure leaves room for power-hungry people to migrate to the place where they can wield power.

Something else about California, John–we have a shorter length of stay than other states, and lower per case prices.

About health plans being the negotiator: we have an organization called the “Integrated Healthcare Association,” composed of all the other healthcare associations. It has been a setting for discussing new ways of doing things. It was the locus for developing Pay for Performance, first introduced by Hill Physicians, a 3500-doctor IPA in the Bay Area, now gone national. But they did not do so well when I, as a guest speaker, asked them to consider influencing the hundreds of billions of capitals dollars about to be spent on seismically renewing out older hospital structures. They reported not doing anything at all. (Now 500-600 billion) In the ladies’ room, I asked several women from this group why they did not; they said “We wouldn’t know what to ask. Uwe and others seem to think that health plans themselves are founts of wisdom, better to be relied on than providers or patients. I see them as still operating in a 1930’s casualty insurance mode. Hospitals could have used their help when cities began to extort reparations from hospitals seeking construction permits in the, literally, billions, egged on by healthcare unions. Health plans could have helped their future enrollees and themselves, by representing those interests in front of the bought and paid for elected officials.

So–don’t forget the fixed costs go on, even though a particular procedure has become a “loss leader.” Joints are a good example. But how about a case of MRSA?

Everyone needs to consider all the new tools consumers have, including new aps that offer comparative prices. The market is alive and working ever better just under the noses of policy-makers and regulators, who would like to believe only they can save the public. I’d yawn, except they are so harmful.

I hope this illustrates part of our collective dilemma in healthcare pricing; there are always more layers than you may think, and always more ways to skin a cat than anyone wants to consider.

This is a great debate and should continue.

Wanda J. Jones, MPH, President

New Century Healthcare Institute

San Francisco

Wanda, always enjoy your insights. Keep posting.

My very rough guess is that one half of hospital admissions start with emergency room admissions, and the other half are scheduled procedures such as joint replacements.

If the good application of price transparency forces lower prices for the scheduled procedures, will not hospitals just take their revenge and raise prices for emergency driven admissions?

I have long felt that getting some control of health care costs requires free markets in most areas and price control in a very few areas.

As Wanda suggests, hospitals have enormous overhead costs that they are desperate to force onto someone. Eternal vigilance over their cost shifting is needed.

So, we are now defining the market in terms of “health insurance company DEATH PANELS!” Yea, that’ll work. Remember that next time you need chemo, and the insurance company says we’ll only pay enough to give you 1/3 of what your doctor prescribed (and yes, it happens – on of my people is in that situation RIGHT NOW).

and now the government gets to do it. What an improvement. At least with insurance companies, you were able to chose which plan you wanted

Wellpoint’s thinking was greatly influenced by my colleague, the late Jim Pendleton, MD. Jim laid out a similar idea in Pennsylvania about 10 years ago, only his was a bit more nuanced. Instead of paying a flat $30,000 he would have had the carrier pay a graduated amount above or below the referenced price. If the patient got a better deal she could keep a portion of the savings, if she spent more she would have to pay a portion of the extra on a sliding scale basis. I have Jim’s original paper on this and will send it to anyone who is interested (I don’t think it is on-line anywhere). E-mail me at GMScan@comcast.net

John,

I wanted to let you know that Healthcare Blue Book is working with some leading hospital to have them promote fixed pricing/value to consumers via our platform both for our employer/payer clients and for general consumers on our public website. The concept is for the hospital to disclose and commit to a fixed price for typical inpatient services (which is unheard of for most hospitals today).

We will solve the pricing challenge for the inpatient services similar to what we have done for outpatient services.

John,

Interesting information from California. Is there any data on quality/outcomes or complications from these procedures?

FYI: A hip replacement as at a brand new splendid clinic in Bucharest, Romania (part of the EU since 2007) starts at 5,000 Euro (so I think $30,000 is still way to much for normal folks in the US). Blood tests run from $2 to $20 a piece and you receive them by email.

At the end of the day, free market principles will work in medical care if the same free market principles are used in any functioning free market. That means a competitive bidding process. This is how we have been able ot get prices for our employer groups that are 80% less than chargemaster, and about half of what insurance companies report as “allowables”

Dr. Goodman: before I accept health care competition based on the market, you’ll have to explain how it works for patients seeking care in the ER. The examples you cite, such as Lasik and cosmetic surgery, and walk-in clinics, apply to a small number of Americans which constitutes a very small fraction of the number who visit the ER.

Even most libertarians do not promote competition in the areas of fire fighting and police work. There is no time for price comparison and making informed contracts.

Also we want some service provided to everyone, including those who have no money or no savings.

Instead, we fund these institutions from general taxes rather than user fees.

This is imprecise and might waste a little money……but we live just fine with that imprecision.

If we can accept this small portion of socialism for our property, we ought to accept it for our bodies also.

I would like to see ER’s funded primarily from taxes and only partly from user fees. I could get behind a cap of $250 as the maximum patient bill, and an increase in taxes to cover the rest so that hospitals do not close their ER’s.

Logistically this would not be easy, there are many opportunities for financial waste here.

Still, I would like to see at least part of hospital care be taken out of competition.

And incidentally, I would love to see competition destroy the ability of hospitals to price-gouge on outpatient care with their ‘facility fees” and $150 per minute operating suites.

Bob Hertz, The Health Care Crusade

Hey, Bob, your urban bias is showing. Most firefighters in the U.S. are volunteers and volunteer fire departments are largely funded not with taxes but with fundraising efforts (bingo games, bake sales, annual carnivals). I would wager there are more private security guards than there are paid policemen. In my area people do indeed subscribe to ambulance/EMT services.

Arguing by analogy is always dangerous.

Your comments on volunteer firefighters made me research. You are correct in that the majority of U.S. Firefighters have a ‘volunteer’ status. Normally the term ‘volunteer’ implies free-gratis; however, in this case, that is not so. Most volunteer firemen do receive compensation.

Also, your term ‘ largely funded’ implies primarily funded. Primary funding comes from City, County, State, and Federal sources. That means our tax dollars … not cupcake sales. Therefore, insomuch that our tax dollars are providing the greatest part of this ‘social’ service, our interests should be protected through legislation by the areas of government providing those funds. Bob’s point is well taken.

In the old days, you paid a premium to a private firefighting service. You put a badge on your door and if there was a fire they came and (if they saw the badge) they fought the fire. If you did not subscribe, they (usually) put out the fire and sent you a bill. You either paid it or they took you to court.

My limited understanding of the history of government take-over of firefighting is that it took place with urbanization a little over a century ago. With the tenements, you could not count on a fire being limited to one house.

In any case, it is a false analogy. Even if I concede firefighting and ERs to the public sector (which I do not), nobody has argued that the public fire department should provide “preventive care” to your house. That is, the fire department does not install your fire detectors, etc.

Furthermore, the fire department puts out the fire. But it’s not a guarantee: If the whole neighborhood is on fire, they have to prioritize. If they get you out of the house safely, they might let your house burn and prioritize others.

Also, the fire department does not indemnify the house and goods inside it. For that, you buy private insurance. Can you imagine the cost to taxpayers if we said that the public purse had to replace the house and furnishings inside it?

But this is what we demand of health insurance. If you fall down on the ice because of a bad hip or knee, getting you in and out of the ER does not finish the health insurer’s obligation. They pay for a hip or knee replacement. Indeed, if you suffer burns in a fire, the health insurer will pay for the plastic surgery (because it is therapeutic, not cosmetic.)

“If you did not subscribe, they (usually) put out the fire and sent you a bill.”

John, maybe not always.

I lived in St Louis in the late 1960’s when there was a huge controversy that involved a volunteer fire department in one of the near suburbs (no way was this a rural area). One evening, the VFD was called to a residential fire only to discover the homeowner had not paid the VFD dues. The neighbors on both sides had paid their dues, so the VFD hosed down their roofs to protect them from flying embers.

Many people frantically offered to pay the dues for their neighbor’s burning house. The VFD refused to accept any payment and the burning house was destroyed. VFD defended its action on grounds that, had it accepted payment at the time of the fire, the VFD would cease to exist and the entire community would be left without protection.

A judge eventually ruled in VFD’s favor but in the end, no one was really satisfied.

True story. I doubt it was unique for the times.

That is interesting and disturbing. But nobody died, right? I think I might side with the VFD, but I’m not convinced.

The problem is that an urgent and emotional plea from the neighbors is unlikely enforceable. So, unless they had the money available in banknotes, their promises to pay might not have been worth much.

Plus, it would be a little absurd to expect the firemen to handle money (or checks or credit cards or gold coins or whatever means of payment) when they have arrived to fight a fire. That needs to be handled in the office before the fact.

So, the neighbors might be so distressed by what happened that they incorporate as a small village and levy taxes to pay for the service. In this case the cost of firefighting is, indeed, socialized.

However, it is only socialized amongst a few dozen households. It is not socialized amongst an entire nation covering half a continent and containing 330 million people. Thus, the burden of socialization is much smaller.

Similarly, with respect to health care, it is often argued that “we won’t let people die in the street”.

Fair enough: So, let the city council figure out how to pay for emergency care for those who cannot pay. For the federal government to tax the people, move their money through the IRS to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, back to state capitols and county seats, introduces a lack of accountability, friction costs, and bureaucracy that would not be tolerated if the socialization of the ER costs were limited to the local jurisdiction.

In K-12 eduction, we have suffered the same problem over the last half century or so.

I expect a rebuttal along the lines of “What about Detroit or Chicago?”, to which I answer “Don’t live there, and don’t let Congress tax you to bail them out!”.

I regret I have no perfect solutions. I think the best summary of the situation was by Mark Steyn: “Government can work tolerably acceptably under two conditions: 1: It is local; 2: There are no unions involved”.

Interesting discussion. To expand it a bit, about four years ago I included this item in my Consumer Power Report —

Uwe Reinhardt sent me a short video showing a fire department working under supposed capitalist conditions. An apartment building is in flames and the firemen have only one net to catch the people trapped inside, so victims in various apartments start bidding to be the one person who can be saved.

It’s pretty amusing and is intended to suggest that capitalism and health care don’t mix. But, does it really? I think it shows just the opposite.

First, the public (socialized) fire department is clearly under equipped for the task at hand. Ten or so people need to be rescued but they have only one net. That being the case, how should they allocate the resource? By random lottery? Or by choosing the person most worthy of rescue by some criteria — perhaps a child with the most years yet to live, or perhaps an elderly person who merits being saved for her many years of service to society, or perhaps the person with the greatest earning potential who will contribute the most to society’s well-being in the future? Or, most likely, the city councilman who votes on salary increases for the firemen holding the net? Are these methods better than an auction?

More importantly, with all these people bidding to be saved, a capitalist fire department will not want to forego the earning opportunity. It will invest in more nets to save more people and collect more money.

So it was with Ben Franklin and his privately owned Union Fire Company, which later led to the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire. By the way, this company did not believe in Community Rating. It charged wooden houses triple the premium as brick houses and denied coverage for houses with trees in front of them.

SOURCE:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bnjQ3cV4x1I

Fire Fighter Video

Competition can work in the ER as well. I see signs everyday boasting real time constantly updated wait times. Time is money too. Since i charge $650 an hour when I consult, time is very valuable to me.

On MediBid, ER is handled differently. Obviously there is no time for live bidding on the way to ER, so we do allow them to feed us a daily price.

It seemed easier than it would have been to install an app in every ambulance

When I was in San Francisco, I saw advertisements on the sides of buses from competing hospitals’ ERs all the time. However, they were competing on waiting time, not price. I understand that unscheduled surgeries admitted from the ER are very profitable for hospitals.

Plus, if (as discussed frequently at this blog), many visits to ERs are not really emergencies (due to EMTALA and other rules) we cannot look at the current ER caseload to tell us how much health care is really emergent.

“Patients were free to go to elsewhere, but they were told in advance that WellPoint would pay no more than $30,000 for a joint replacement.”

That sounds similar to balance billing something Medicare should consider.

It also incentivizes physicians to become staff members in less expensive hospitals for they will have treated patients for years and when the time comes to operate the patient might feel forced to find another doctor.

Greg, you are right I am a city kid, where firemen are paid employees.

Even in the country, I suspect there are tax dollars paying for the buldings and equipment. Bake sales cannot fund a $300,000 rig.

Also, Greg, can you explain what you mean by subscribing to ambulance services?

Does no one pick me up if I fail to pay my subscription? In St Paul MN the fire department provides most of the ambulances, and paramedics work for the fire department. Maybe we are in a liberal island?

Ralph, you do great work, but your comment also stumped me. Do you imply that ambulances should cruise the city looking for the cheapest ER? Or should they go 50 miles out of their way from one suburb to another to get a lower price? Please expand.

I do tend to see the darker sides of privatization, especially in the hospital sector.

You guys seem to imply that we can come on the far side of privatization with competitive good services. I am from Missouri on this, I guess.

John, great post and great Comments. I’ve enjoyed reading very much.

My only “add” is that consumer driven pricing is very important and can be quite effective in outpatient settings and procedure driven interventions, but this inpatient consumer driven pricing was made possible by the large and powerful third party Payor – plain and simple. I know that you are going to hate this statement, but in my humble opinion, You and Uwe are both right!

The lesson here is that, in healthcare, we have to have large Third Party Payors to exert pricing pressure upon the large institutional providers. Wanda Jones expressed the rationale for this very well insofar as institutional providers have very large fixed costs that must be allocated to the consumer through their third party providers. I was personally a hospital administrator for 25 years and it is a miserable profession due to the cost and reimbursement pressures of operating a high quality hospital.

Consumers cannot possibly influence the cost of healthcare by themselves alone. The healthcare system is far too complex and monopolized in most areas of the country by a few large Providers. The larger Third Party Payors exert a significant positive influence over the institutional Providers in this country. Our overall cost of providing healthcare would be much, much higher than it is today if these Third Party Payors were not around. Additionally, Coordination of Care efforts by IPA’s like Hill Country Physicians and IntegraNet Physician Resource are also making a positive difference in the health status of the members of these third party Payors; resulting in huge reductions in the cost of healthcare.

Note to John Graham — thanks for your comment on fire departments vs the ER. That is the most intelligent comment on my pet analogy that I have read in some time. We do expect health insurance to go well beyond emergency care.

However I am not comfortable with your first paragraph about how fire departments used to work in more rural areas…….”they put out the fire, and then if you did not pay their bill then they took you to court.”

I guess I am a liberal because I think a society where fire victims who have no house are then dragged into court is kind of barbaric. I am glad to pay a small amount of property tax so that the service is free to all. In my system, granted, a few people are still taken to court if they do not pay their property taxes….

All modern health care systems require a certain amount of financial coercion. Coercing people to pay taxes seems better to me than coercing them to pay medical bills.

Of course there must be limits. The property taxes to support a fire department are peanuts compared to the income and payroll taxes needed for full single payer health insurance.

Well, if they put out the fire, you have a house. If they didn’t put out the fire, you sleep at the school gymnasium until you get yourself sorted out, so there is some kind of safety net.

More seriously: There is the element of local control and tax base. I suppose we expect a national standard of firefighting, and that firemen have the same expertise wherever they are.

However, I would not expect a firefighter in Manhattan to have the same skills as one in rural Idaho. They face very different challenges.

Imagine what firefighting would look like if it were funded primarily by federal taxes and borrowing, and run by regional bureaucrats (like Medicare is). Water-hose manufacturers would have a trade association stuffed with veterans of Sen. Baucus’ and Sen. Grassley’s staffs, lobbying for changes to the “Firefighting Fee Schedule” to increase their reimbursements!

If we go back even just a half century or so, there was no federal involvement in private health care (except for federal jurisdictions such as military and mariners). There was precious little state involvement outside the criminally insane. If the people of a community wanted to fund a non-profit hospital, they got together and did so – often along denominational lines.

I struggle to find a good argument for a federal rather than a local safety net.

Good points, John.

I suppose the liberal fear is that in areas of racial tension, the majority might explicitly decide not to fund emergency care for the poor.

That did happen in the Deep South before Medicare. It is not hard to find accounts of black accident victims being turned away from hospitals.

But if you can overcome that objection, your argument for local control is very tempting.

(The quote from Mark Steyn about local non-union government is interesting. Sounds like he was thinking about the British NHS.)

“black accident victims being turned away from hospitals.”

Bob, are you talking about things like our first lady did… dumping?

“Michelle Obama Accused of Turning Away Poor Black Patients”

http://sandrarose.com/2009/03/michelle-obama-accused-of-turning-away-poor-black-patients/

No Allen I am not.

The people turned away by the U of Chicago hospitals thanks to Michelle were almost certainly treated at a county hospital.

The people turned away from Southern hospitals sometimes bled to death. I believe that is how Bessie Smith died.

I am not saying it happened every day, nor that we needed Medicare to fix it. I am only saying that local governments are not always generous. Read T H Watkins’ history of the Great Depression for more examples. People did starve to death in the 1930’s when federal aid was in its infancy.

Dumping can lead to death whether the person is black, white or any color or any religion. You don’t have the slightest idea whether or not that Michelle Obama’s type of dumping led to the death of not just one, but many black people so you shouldn’t be making the statement that they “were almost certainly treated at a county hospital”. Moreover the care at the county (other community) hospitals is not thought to be as good as the University hospital so that is a second problem you face in your argument, a long term one that negatively affected many people of color.

[Note: The reason anti dumping laws were created was that patients died in transit or died because of delays in treatment or treatment in facilities that lacked the needed infrastructure to provide the needed care.]

Yet you provide a singular anecdote and discuss things that happened in the distant past that no one Republican or Democrat agree with. At the same time you try to justify the prior actions of the wife of the President of the US dumping many blacks into an inferior hospital where the dumping might have been a contributing factor to subsequent deaths. What Michelle Obama did was racist against her own people, unethical and unbecoming to a First Lady as well as unbecoming to any American.

Take note the shuttle buses they used to dump these patients weren’t much different than the buses used to rid communities of unwanted people, many of whom were black. Also take note that the way the dumping was put to the people of the poor community, mostly black, was an attempt to convince them that the University was being charitable and that the dumping would lead to better care. Now they are using the same method to convince all the American people that Obamacare is a step towards Nirvana.