Reforming Health Insurance to Promote Diagnostic and Pharmaceutical Innovation

Sovaldi is a wonder drug that effectively cures a strain of the Hepatitis C virus. The headline price of Sovaldi is $1,000 per pill, or $84,000 for a course of treatment. Too expensive? That’s what the head of the health insurers’ trade association says, and many agree with her.

This charge is inaccurate. The problem with Sovaldi is that all the costs are upfront. Spending $84,000 in a few months will potentially save hundreds of thousands of dollars down the road. As Margot Sanger-Katz wrote in the New York Times:

Research on the cost-effectiveness of Sovaldi is still in the early stages, but it appears that use of the drug has the potential to actually save money over the long run. Data from the C.D.C. suggest that more than 60 percent of people with hepatitis C will end up with chronic liver disease — and as many as 20 percent will end up with cirrhosis. Treating those diseases is costly. A liver transplant, the most expensive option for the small group of patients with end-stage disease, costs nearly $600,000.

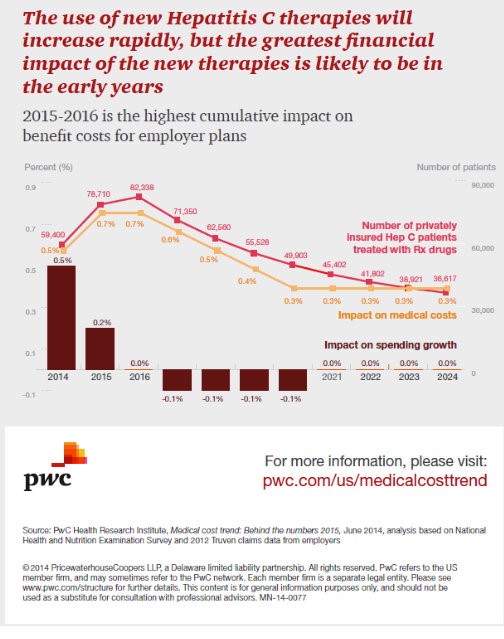

This development can take twenty or thirty years, and not every Hepatitis C patient will end up needing a transplant. Nevertheless, according to the PriceWaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute, Sovaldi will reduce long-term medical claims for employer-based plans.

Pent-up demand for Sovaldi and other Hep C drugs on the horizon will drive up medical costs in 2015 and 2016 by 0.7 percent per annum year, because about 80,000 patients each year will be treated with these drugs. However, as early as 2017, this will lead to a very slight reduction in overall spending growth, as patients cured in 2015 and 2016 stop incurring long-term costs.

And yet, the health insurance industry is extremely upset about Sovaldi’s price. Sanger-Katz continues:

The United States health insurance system works better for costs that are spread out and predictable. People change insurance frequently, discouraging insurers from making a big investment now that might pay off later.

Perhaps Medicare, which owns its patients for life, has a better incentive to pay up early for long-term benefits. A report by actuaries at Milliman concluded that Medicare beneficiaries with Hepatitis C have three times the medical costs of the average Medicare patient. Unfortunately, Medicare also has poor incentives.

Medicare has about 350,000 beneficiaries with Hep C. Scholars affiliated with the Kaiser Family Foundation have modeled a scenario in which 75,000 of them get Sovaldi, increasing Medicare Part D costs by $6.5 billion, or 8 percent. Medicare Part D insurers do not benefit from reducing costs to the rest of Medicare, or costs beyond the current year.

Plus, because voters seem largely immune to Medicare’s looming insolvency, politicians have no incentive to reform the government program so that it pays for treatments that save money over the long run.

As for other government health plans: 750,000 people with Hep C are dependent on Medicaid or in prison, according to Express Scripts. Treating them all with Sovaldi would cost states $55.2 billion. Interviewing Matt Salo, who represents state Medicaid plans, Sanger-Katz continues:

State Medicaid programs are particularly sensitive to annual cost increases. Medicaid coverage is paid for, in part, out of state budgets, which have to be balanced every year. A disproportionate number of infected people rely on it for insurance, because the population most at risk — intravenous drug users — tends to be poor.

“From a realistic perspective, when a Medicaid budget skyrockets like that, you aren’t going to hear from the U.S. taxpayer, ‘Thank goodness, Medicaid was here to solve this public health crisis,'” Mr. Salo said. “They’re going to say, ‘It’s another runaway government program.'”

And it gets worse. There is a lot of uncertainty over how many people in the U.S. have the disease. Milliman estimates 3.2 million, of which over half a million are in prison. However, there is no requirement to screen prisoners for Hep C. Of the remaining approximately 2.6 million, about 1.8 million are undiagnosed.

Obviously, these people are highly likely to transmit the virus to others. So, better diagnosis and treatment would have a knock-on effect. Unfortunately, incentives to diagnose and treat the disease are awful, and Sovaldi has actually made the incentives worse. Insurers and governments are less likely to seek out likely patients to screen, because diagnosis will just bring a gigantic drug bill.

A solution is one that NCPA has endorsed for a long time: Individually owned insurance that includes insurance against the costs of chronic illness (called health status insurance). Instead of forcing people to get health insurance that lasts only one year, this health insurance would take into account a person’s lifetime cost of illness.

As a result, unproductive conflicts like the current one over Sovaldi would recede from prominence. Insurers would have an incentive to screen patients early and often, in order to nip expensive conditions in the bud. Diagnostic and pharmaceutical innovation would accelerate, as insurers become more willing to pay up for tests that diagnose early-state illness and drugs that bring long-term benefits.

Unfortunately the up-front costs dissuade a lot of people from pursuing treatments that are cheaper in the long run

Upfront costs are one of those issues that very, very few people have the smarts to look beyond.

Patients with Hepatitis C can remain asymptomatic for 20-30 years. Nobody knows how many of those will get sick and die of something else such as heart disease or cancer or die in an accident before any symptoms related to Hepatitis C appear. I don’t think aggressive screening makes a lot of sense. Instead, as the medical director for the Illinois Medicaid program suggested in an interview with the WSJ, Sovaldi should be limited to the sickest patients and any of those who abused drugs or alcohol within the prior 12 months should be denied treatment because they are likely to be non-compliant in taking the drug.

Separately, I also think it’s inappropriate for GILD to charge different prices to patients in different DEVELOPED countries. While there are a lot of legitimate reasons to practice price discrimination, I don’t think differences in per capita GDP is one of them. Secondly, I think drug companies need to do a better job of balancing their need to earn a satisfactory return on invested capital to give them the incentive to innovate and to cover the cost of R&D failures with society’s ability to pay. As I’ve noted before, people don’t buy these products because they want to but because they have to and a significant part of the bill is paid by taxpayers.

In this instance, I think the argument suggesting that Sovaldi will save money in the long run is weak because we can’t quantify how many people will die of something else before Hepatitis C becomes life threatening and how many will have expensive to treat co-morbidities even if we cure their Hepatitis C. Finally, since such a large number of those with Hepatitis C are drug users, they are not the most sympathetic patient population as compared to, say, veterans.

That seems to be the gist of the proposals. Even in Medicare, the highest proportion modeled is to treat 75,000 of 35,000.

I doubt very much that the prison and Medicaid system would treat everyone, as was modeled by Express Scripts.

Consider that the $600,000 for a liver transplant in 30 years has a present value (at 6% annual interest) of about $84,000. Not much of a saving here.

Thank you. It is not that their are only the cost of the pills or the cost of transplantation. There are large and increasing costs over the years as the disease is not treated.

“The United States health insurance system works better for costs that are spread out and predictable. People change insurance frequently, discouraging insurers from making a big investment now that might pay off later.”

This is why it is better to provide portable health insurance to individuals. That way insurers do not have the disincentive from making that “big investment.”

“Insurers and governments are less likely to seek out likely patients to screen, because diagnosis will just bring a gigantic drug bill.”

Wow. So this, in turn, will have a adverse unintended consequence. It will lead to an increase in those undiagnosed and lead to a higher infection rate.

While I feel health status insurance could be beneficial to combat unexpected costs when people’s status changes (ex. becomes a diabetic), the idea of having insurance for your health insurance is off putting.

I agree. Having to insure your insurance seems counterproductive.

You probably would not have to buy it yourself. I expect it would be bundled into what we currently recognize as health insurance, and the health insurer would re-insure the health-status risk.

The high cost of Sovaldi combined with the perverse incentives of Medicare, Medicaid and insurers are a toxic combination for individuals with Hep C.

As if having Hep C is not bad enough by itself.

In the health insurance market, the cost of traditional reinsurance depends on the attachment point which is the aggregate dollar level of claims that needs to be reached before the reinsurance kicks in. I’m told that even a $100K attachment point would be considered low today which means it would be expensive insurance to purchase. To get the cost to an affordable level, the primary insurer or self-funded employer would probably have to accept a $250K attachment point.

The reinsurance program that’s part of the ACA’s 3 R’s reinsures claims above $45,000 up to a maximum of $250,000 and the primary insurer reassumes liability after that. The most expensive claims within the commercially insured population tend to be for low birthweight premature babies, especially multiple births. These cases can and often do run into seven figures.

I don’t think reinsurance or health status insurance as a mechanism to protect people against the cost of health insurance based on medical underwriting after they become sick would be workable. Where would the money come from, who would pay into the fund and how would it be administered? The total cost could well prove to be as much or more than the basic insurance itself. The most likely alternative is risk adjustment payments though the risk adjustment state of the art is not yet where it needs to be. Risk adjustments still tend to overpay for the healthy and underpay for the sick and, to the extent that the adjustments are claims based, there is a lag between the time claims are incurred and when they get reflected in the individual patient’s risk score.

It would not be a fund. But that is not the main thing. It would not take any more money than is now taken, because it has no direct effect on the cost of medical claims.

Hi, John and All.

Accidentally, I happened to be reading an article about Gilead and Sovaldi. It quoted the huge up front costs but gave the cost of a pill at only $130 to manufacture. (Avic Roy, Forbes, 61714) It is attempting to recoup all its investment in this drug, from buying the inventor firm, in one year–not standard procedure. It is also discounting massively in other countries. I see the reaction as justified and think the field should watch out for new calls for price regulation.

Wanda J. Jones, MPH

San Francisco

I’m pretty sure that the $130 figure is the marginal production cost for a 12 week course of treatment (84 pills) which works out to $1.55 per pill. GILD’s stated price per pill ranges from $1,000 in the U.S. to $10.00 in Egypt with lots of different prices among other countries. Developed country pricing is based on differences in per capita GDP which is hard to justify in my opinion. If the manufacturing cost were $130 per pill, that would be $10,920 for a course of treatment which suggests that GILD could not afford to offer it for $840 per course of treatment in Egypt.

I don’t know what the “right” price would be in the U.S. or anywhere else but I think $1,000 per pill is grossly excessive. Hopefully, the pushback will come, in part, from limiting access to the drug to the sickest patients with Hepatitis C and not just anyone who is infected with the virus whether they have symptoms or not.

As a Hep C survivor, I resent that you associate Hep C with convicted criminals. Many, many Hep C patients are stand up citizens, not convicts.

Thank you. As stated in the article, estimates are that 3.2 million Hep C patients are in the U.S., of which about half a million are in prison.

That leaves about 2.7 million out of prison.

I don’t really know much about Hepatitis C. I looked it up on WebMD and this is what is said…

You cannot get hepatitis C from casual contact such as hugging, kissing, sneezing, coughing, or sharing food or water with someone. You can get hepatitis C if you come into contact with the blood of someone who has hepatitis C.

The most common way to get hepatitis C is by sharing needles and other equipment (such as cotton, spoons, and water) used to inject illegal drugs.

Before 1992, people could get hepatitis C through blood transfusions and organ transplants. Since 1992, all donated blood and organs are screened for hepatitis C, so it is now rare to get the virus this way.

In rare cases, a mother with hepatitis C spreads the virus to her baby at birth, or a health care worker is accidentally exposed to blood that is infected with hepatitis C.

Experts aren’t sure whether you can get hepatitis C through sexual contact. If there is a risk of getting the virus through sexual contact, it is very small. The risk is higher if you have many sex partners.

If you live with someone who has hepatitis C or you know someone who has hepatitis C, you generally don’t need to worry about getting the disease from that person. You can help protect yourself by not sharing anything that may have blood on it, such as razors, toothbrushes, and nail clippers.