Medicare Experimenting with Bundled Payments for Hip Replacement

According to a Wall Street Journal article, Medicare is experimenting with how it pays some 800 hospitals. The bundled payment initiative will hold hospitals accountable for the cost of hip replacements for 90 days after surgery. Complications or inefficient care will eat into hospitals’ bottom line.

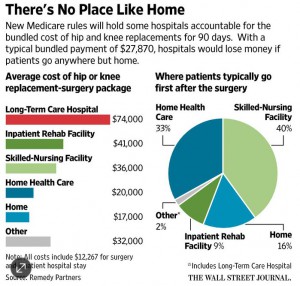

At issue is the rising cost of post-acute care. Those are the costs Medicare pays for seniors to convalesce after an acute care hospital stay. For example, if a senior has a hip replacement and is admitted to a long term acute care hospital (like I used to work at), the total cost runs about $74,000 on average. If a Medicare beneficiary is sent to an inpatient rehab facility after hip replacement, the total cost is $41,000. A senior discharge to home with home care costs $20,000, while one sent home without home care costs $17,000.

As you can probably imagine, Medicare is organizing its bundled payments in a convoluted way. Medicare is not giving hospitals a lump sum to divvy up among the various providers of care. Rather, Medicare is paying the charges on a fee-for-service basis and going back at the end of the year and calculating whether the total 90-day cost of care exceeds a benchmark. If total payments are lower, the hospital gets the savings. If total costs exceeds the Medicare benchmark, the hospital owes Medicare the difference. (I have an idea: just tell the hospitals how much the benchmark is, let them control the dollars and keep the savings. It would work much better.)

Medicare wants to discourage the unnecessary use of post-acute care. Hospitals are paid a fixed diagnosis related group (DRG) payment based on a policy that began in the early 1980s. The idea was to reimburse hospitals for caring for the average patient, while also encouraging hospitals to discharge patients quickly rather than pay for long, unnecessary hospital stays. But rather than eat the cost for caring for the outliers, hospitals found another way to move seniors out of the hospital into another hospital-owned facility where care was reimbursed. On the one hand, post-acute care facilities are much cheaper than hospital stays. But on the other hand, they can be used as a loophole to pad the bill. The hospital where I worked 25 years ago opened one of the first long term acute care facilities. The idea was to take very sick patients out of the big parent hospital, where reimbursements had ceased (DRGed out as we called it) and admit them to a neighboring hospital (it was across the street) where the patient would be cost reimbursed due to a loophole in earlier payment rules.

The key word here is experimenting. If it doesn’t work, CMS will have to try another approach. In theory, hospitals should have the management infrastructure to equitably divide up a bundled payment among all providers involved in each case.

In theory, CMS could tell the hospitals what the benchmark amount is and offer to let them manage the dollars. At the same time, if the alternative is to stick with the FFS status quo which is much less risky for hospitals, it’s questionable how many hospitals would be willing to accept the risk inherent in the bundled payment approach assuming they have a choice.

It seems whenever Medicare wants to use positive incentives, it is so lacking in knowledge that the bureaucracy cannot allow the incentives to work unattended.

In Accountable Care Organizations, rather than assign enrollees to an ACO and tell the ACO who they are, Medicare tells the ACO a year later who its members were the previous year.

In this case, rather than tell the hospital what the benchmark rate is and put the hospital in charge of paying various providers, Medicare pays the bills and tells the hospital a year later whether they get money or have to pay some back. If the hospital controlled the funds, it could probably enter into some beneficial collaborations to provide efficient care. This way, the hospital has no leverage to entice other providers to participate.

I agree with all that. I don’t understand why CMS isn’t prepared to take some risk and pilot your suggested approach with a limited number of hospitals who volunteer to give it a try.

If hospitals control the funds, the surgeons become virtual employees. The problem is hospitals know nothing else but controlling the funds. To reduce costs by using a cheeper, antiquated joint prosthesis, inferior anesthetic agents, less than optimal suture material, and lesser use of antibiotics all save money in the short run, but at what cost. Better packaging, newer more patient specific prostheses, anesthesia that enhances pain management are all integral to better patient care and long term outcomes, not to mention process and prosthesis improvement. The least costly and optimal outcomes are related to outpatient surgical settings. Inpatient hospitals are intrinsically inefficient.

Control of the financing by hospital administrators who know nothing about joint replacement or the fantastic associated advancements should not have this degree of control. It begins to suggest the corporate practice of medicine.

Finally, it places physicians in the middle of an ethical dilemma. Should better patient care or compromise for the sake of a short term 3% savings for a hospital be a decision any physician needs to make? Placing hospitals in total control of funding for these life saving and quality of life decisions is wrong.

If the hospital values its reputation and wants to achieve good outcomes, it presumably wouldn’t cut corners in the way you describe. Don’t chief medical officers have significant input into decisions like that?

Moreover, surgeons who generate a lot of profitable business for hospitals will not only be able to negotiate a satisfactory fee for their work but also appropriate control over the equipment, supplies and drugs needed to perform the procedure safely and effectively.

“If the hospital values its reputation and wants to achieve good outcomes, it presumably wouldn’t cut corners in the way you describe.”

Bull.

“Moreover, surgeons who generate a lot of profitable business for hospitals will not only be able to negotiate a satisfactory fee for their work but also appropriate control over the equipment, supplies and drugs needed to perform the procedure safely and effectively.”

Logical fallacy.

Devon, it appears that the government is in a quandary. They created the problem believing there is a magical way of determining who needs post operative hip surgery care in an institution and who needs it at home.

When I looked at the literature more than a decade ago it appeared that the benefits from institutional care after hip surgery didn’t improve outcomes. How valid those studies were I am unsure of, but assuming there is no improved outcomes why does Medicare pay for it in the first place? Maybe certain subsets could benefit, but such subsets are not clear and predictable so who should be institutionalized or not may be little more than a crap shoot. Is Medicare asking hospitals to roll the dice?

Perhaps the expert in this situation is the patient who knows his or her capabilities. How do we get them to make a good judgement call if the primary concern is reducing costs? Skin in the game.

When I worked for a long term acute care hospital, the concept was so new the doctors did but really understand our purpose. Many of our patients in the early days were either ones who needed a long convolescence, and were generally discharged to a rehab facility. Or they who left on a gourney with a red velvet blanket draped over them and were picked up by the funeral home. Our first few months in existence over half our patients took the latter route.

I wonder if those going to long term acute care after hip replacement are those who were not good candidates for hip replacement in the first place?

There are many things involved with hip fracture and its remedy, surgery. Sometimes it is palliative. There can be a lot of pain if left untreated. Not infrequently a patient fractures their hip while living in a nursing home. Sometimes in the very ill the surgery takes a lot out of the patient and they need more than the usual help after surgery. Sometimes they even die post op.

The problem is those that are making policy are too far removed from the trenches to actually know what is going on.

One problem with this initiative is that a bureaucratic program is forcing bundled payments using monopsony power. There’s certainly nothing wrong with that. But proponents of bundled payments often see payment bundles as a beneficial arrangement in and of itself.

Without actual competition, all of the benefits of bundled prices are not likely to occur. The only benefit will be Medicare demanding price breaks using its monopsony power and wily providers have ways of circumventing that since they do not gain from competing on price.

But what makes bundled payments the norm in every other market is competition. Suppliers know there is a limit to how many “gotchas” consumers will withstand. Suppliers also know that consumers can sometimes be enticed with a deal. Thus, car dealers quote a base model car as a loss leader they don’t expect anyone to want. The base model car is a bundle (that is: tires and engine and assembly are included). The automaker (and its dealers) then tally up all the overpriced optional items on the sticker price. Generally, the additional options come as packages.

Bundling is in response of competition, but also for purposes of convenience and marketing. Bundling often forces the consumer to buy more options that he/she would otherwise order (sort of how my cable has Lifetime and SPN). Health care does not bundle (except in cosmetic surgery) because is it not competing on price and knows piecemeal pricing will boost revenue (at the price of efficiency)