How Safe Is Your Hospital?

Hospitals are dangerous places to be. At least if you are a patient. In a Health Affairs study, my colleagues Pam Villarreal and Biff Jones and I estimate that as many as 187,000 patients die every year for some reason other than the medical condition which caused them to seek care. We also estimate there are 6.1 million injuries caused by the health care system, including hospital acquired infections that afflict one in every 20 hospital patients.

We estimate the economic cost of this loss of life and limb at between $393 billion and $958 billion in 2006 dollars. This is equal to between $4,000 and $10,000 a year for every household in America.

Roughly speaking, every time the health care system spends a dollar healing us, it causes up to 45 cents worth of harm. Of course, the system also does a lot of good. In fact the good is many, many times greater than the harm. Still, the cost of adverse medical events is so huge we would be foolish not to try to find ways to make it smaller.

Readers may wonder whether our study exaggerates the real size of the problem. The data on medical injuries comes from a study that was completed last year. However, our hospital mortality estimates are taken from a Harvard University study that is now 20 years old, using data that is 25 years old. This is the same study that formed the basis for the widely-cited Institute of Medicine (To Err is Human) finding that between 44,000 and 98,000 patients die every year because of preventable medical errors. You might suspect that hospitals have gotten better since then. Perhaps they have, but with so many patients now receiving outpatient surgery, the impatient population has become sicker and more vulnerable.

Moreover, a study just released finds that one in every three inpatients experiences an adverse event, including falling down, and suggests that our mortality estimates may be too conservative. For example, we estimate that the odds of a patient dying for some reason other than the medical condition which caused the patient to seek care in the first place is as high as one in 200. The newer study places those odds at one in 100.

To put those numbers in perspective, consider that a rule of thumb for many federal regulatory agencies is that any chance of death lower than one in one million is unacceptable. If we regulated hospitals the way we regulate the environment or consumer products we would have to close every hospital in America.

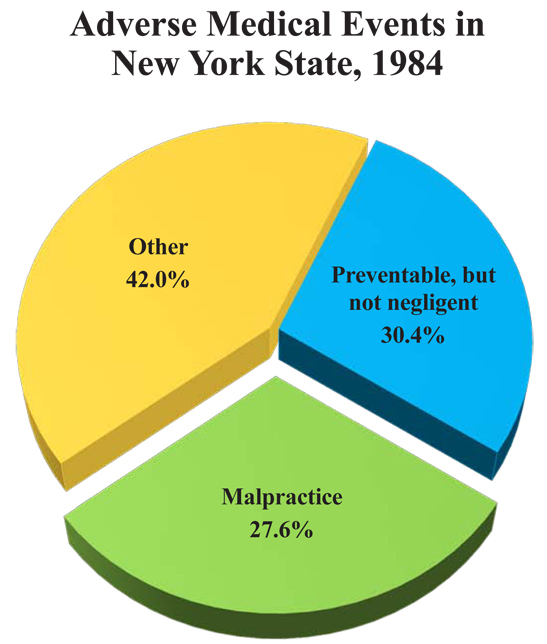

Our traditional method for dealing with this problem is through malpractice litigation. Yet, as the graph shows, only about one-fourth of adverse medical events involve actual malpractice. Even in these cases, the system is highly imperfect. Only 2% of victims ever file a lawsuit and even fewer receive any compensation. Also, more than half of all the money spent on malpractice litigation goes to someone other than the victims and their families.

Moreover, in forcing providers to focus on malpractice, we are encouraging them to do things that may make the overall problem much worse. To protect themselves from lawsuits, for example, doctors may order more blood tests and other procedures. But if those tests have potential adverse side effects, the risk to the patient may go up even as the risk of malpractice lawsuits goes down.

Fortunately, there is a better way. For the money we are now spending on a wasteful, dysfunctional malpractice system, we could afford to give the families $200,000 for every hospital-caused death. We could give every injury victim an average of $20,000 — with the actual amount varying, depending on the severity of the harm.

I’ll explain how to do that in the next Alert. Both Alerts are based on a piece I wrote for Town Hall last weekend and readers may comment on that post as well.

This was obviously written well before John Goodman was properly warned by me recently that the patient safety research of the Harvard Group in New York and Utah/Colorado was not reliable.

When I saw a blip that John was about to publish some big patient safety essay, I warned him. I sent him a paper I wrote for the American Council on Science and Health (available here http://www.acsh.org/factsfears/newsID.487/news_detail.asp), that was in depth and published in an earlier form in the Journal of the Texas Medical Association. So, tonight I saw this terrible hit job on American medicine at TownHall (http://townhall.com/columnists/johncgoodman/2011/04/16/how_safe_is_your_hospital) under John’s handsome face with an internal link to the original piece he did for Health Affairs (http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/4/590.full.pdf+html?ijkey=tRslSgwN8evoA&keytype=ref&siteid=healthaff).

I can’t decide if I am mad more than I am disappointed. I don’t need my friends to do this to me, and to my profession. This research is terrible and it vilifies American Medicine and medical care providers based on terrible and unreliable, politically motivated research.

I could see this coming when John spoke favorably about penalties for hospitals and physicians for bad outcomes or infections at a speech he gave at the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) last spring. I damn near fell off my chair. It went under the radar for the AAPS members who were there because they knew John was generally an ally. If they had noticed I am not sure what would have happened. I just hoped at the time it was a misstatement—it sure the hell wasn’t. John is after us and thinks we are dangerous—I am offended and outraged.

I was afraid to think then that John had turned into another doctor hospital hater. It was very alarming. It came a couple of years after I had to hold myself in check when one of John’s NCPA colleagues, Devon Herrick, started quoting the New York study and Institute of Medicine (IOM) study from the podium in Chicago at a Heartland meeting like he knew what he was talking about and he had to inform the audience how dangerous us docs were, and how we were killing people in hospitals. Devon sure knew a lot about medical care at the time. It’s amazing how many economists and social scientists know so much about medical practice.

John Goodman and NCPA, his baby, have this agenda that they want to resurrect the old Troyen Brennan, Clarke Havighurst, Patricia Danzon project of no-fault malpractice compensation. Too bad another administrative state program is not what NCPA should be thinking about. Particularly when they don’t know the faulty nature of the research on patient safety they rely on.

Having NCPA on this campaign is downright maddening, considering they are the fine organization that pushed HSAs/MSAs and showed how American medicine is good compared to socialist medicine, and less government meddling and more free market would right the ship and correct some problems.

This is no time for talking more government interference.

The numbers that John and his two NCPA coauthors use in the Health Affairs study are from the New York and Utah/Colorado studies that were led by Troyen Brennan. They are the basis for the IOM monograph, To Err is Human (1999 release, pre pub).

In the NY study they decided more than 50 percent of all deaths, even deaths of terminally ill patients, were negligence deaths. That’s called outcome bias, but bias is what people do when they are on the hunt. IOM is intent on proving that the health care system is a mess and needs their tender attentions—since they are all elites and very smart. The target is docs and nurses and hospitals. The hunters are elites with clipboards and an attitude.

The New York study group admitted that Kappa (level of agreement) for physician judgments of negligence was 0.4, which means their agreement between two reviewers on negligence was less than a coin toss. A coin toss gives you a Kappa of 0.5., Kappa of 1.0 is 100% agreement. In the Utah/Colorado study, Troyen Brennan and Thomas, his fellow and the other author, got rid of that inconvenience and just decided together what to call adverse or negligent.

Before he read my paper, written 5 years ago (available here http://www.acsh.org/factsfears/newsID.487/news_detail.asp), John Goodman assumed he knew stuff—he doesn’t, and he was terribly misled by his coauthors if he relied on them. However, he saw my paper that was put on the ACSH website only last week. Too bad, now I have to wonder. John, the Harvard group agreed they had some problems, as I will discuss below.

I am dismayed that this paper will give policy people and particularly readers of Health Affairs, who are professional finger pointers anyway, more reasons to distrust American medicine and hospitals, for what—so John Goodman can run the no-fault project up the flagpole again? The Utah/Colorado study was born of Brennan’s attempt to get Utah to do no-fault—ain’t gonna happen for many reasons. If it did it would be another major financial and administrative burden for the society and healthcare system. Lots of bogus claims and payouts from a generous administrative program for compensation.

I won’t bother telling you in detail why John’s administrative law compensation program would be expensive and become monstrous. Just consider workman’s comp and disability programs.

Here’s the pertinent section of my paper that includes Troyen Brennan’s admissions about the New York Study John and his coauthors like so much: http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pdfs/Excerpt-from-Dunn-study.pdf

Well, John, I warned you that you were talking carelessly about my profession and a lot of honorable people in hospitals and medical care across the country.

So you can promote you’re goofy no-fault program that would just add another financial nightmare to the cost of healthcare. Every less than ideal outcome would get a pat on the head and some money. That’s how the administrative legal remedy schemes work—until the money runs out.

John Dale Dunn, M.D., J.D.

John:

We looked carefully at the Texas study you cited and concluded that the differences are differences of degree, not of kind. Based on the Harvard study, your odds of dying from an adverse event in a hospital are roughly between 1/200 and 1/500. The Texas study you cited puts the odds at about 1/800. Another study published in Heath Affairs along with our paper puts the current odds at 1/100.

It really doesn’t make any difference which of these odds is the correct answer. They are all off the chart compared to what is regarded as an acceptable risk in regulated industries. Our solution: get rid of tort liability and give people the opportunity to voluntarily contract for no fault compensation for adverse events.

John

Questions:

1. If you DON’T go into the hospital, what are your risks? Does the hospital make things better, or worse?

2. How good are metrics if the rate varies by a factor of 5?

3. What is the evidence that no-fault compensation would lower the rate of adverse events?

4. You could give me an extreme incentive for a patient not to get a blood clot, say pulling my license and seizing all my goods, but I still might not be able to prevent the blood clot, except maybe by over-anticoagulating him. Hammurabi’s system worked pretty well at preventing surgical errors. How do you measure the adverse effects of the incentives?

5. How do you control output without controlling input?

6. Is medicine different from manufacturing?

I think you have too many unknowns and not enough equations. It is all guesswork and systems gaming. There is no substitute for a doctor who knows and cares about the patient, and a team that constantly looks for trouble and has the ability to respond as appropriate.

The best people should be seeing to patients, not looking over somebody’s shoulder. The overseers in my experience are usually clueless.

Jane Orient, M.D.

John (Goodman),

I haven’t had a chance to read your Health Affairs article yet nor the newer one you cite. But I agree with John Dunn that the NY and Utah studies have no credibility whatsoever. Indeed, the whole methodology of a couple of academic physicians poring over medical records years later in the quiet of their office and passing judgment on what the front line Docs should have been doing is suspect, in my opinion. Here is my write-up of this (http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pdfs/Excerpt-from-Scandlen-study.pdf) from my “Hyped Up” paper. Generally, I am appalled at the quality of the research that has been done on this issue.

On the other hand, as you know I am inclined to agree with you on moving to a no-fault system for compensating medical harm. John Dunn equates it with Workers’ Comp, but I don’t see that as a criticism. ISTM that Workers Comp works reasonably well, certainly better than having individual workers sue their employer for harm.

Greg

@Greg Worker’s comp is, at least in many places, a disaster. There are piles of money someplace, but doctors receive miserly payments. To get care, workers may have to lie about the cause of their injury, and claim it is not work-related.

Jane,

You and Greg are talking about two different parts of Workers Comp. The payment-for-medical-care part is awful. But the schedule of payments for injuries part ($X for a lost finger; $Y for a lost leg, etc.) is exactly what I have in mind. You would be able to opt out of the whole malpractice system, but you would have to compensate patients for iatrogenic injuries — whether or not you were a fault — based on a fee schedule known in advance.

This idea could go well beyond health care, BTW. In any interaction between you and me, we could agree in advance to buy insurance to cover anything bad that happens — without any finding of fault — and at the same time forgo our common law rights to sue each other.

John

If one could agree on definition of “iatrogenic” injury. And what about patient compensating doctor for bad results that are the patient’s fault?

@Jane

These are good questions to raise.

In the Utah/Colorado study when three doctors reviewed the records rather than just one, the number of adverse events was cut in half. So obviously it isn’t always cut and dried. I’m well aware of this problem. And there are also other problems, not yet mentioned.

I have two objectives, however:

1. Take care of sympathetic cases. OBGYNs shouldn’t have juries of lay people trying to decide if they did something wrong while looking at parents who may face a lifetime of needed care for their injured child. Let’s get all this insured for, so none of it ever has to go into a courtroom.

2. Get the lawyers out of the way and let the decisions be made by independent entities, using expert opinion.

As for patients contributing to, or even causing their adverse events, I would be in favor of less compensation, or even no compensation. But all these are details.

I would think that most doctors would welcome a change of this sort.

@JohnGoodman There is also the lost wages issue. Is it abused? Of course it is. Plenty of people fake conditions such as back pain to game the system. But it still beats the alternative of each individual worker bringing suit against his employer for a workplace injury.

Greg

@Greg Given the current legal system, that may be true. We have a serious cultural problem: cultural Marxism? Blame the employer, the rich, the man, the doctor, etc.

John,

You know I can’t resist a good battle with a great mind. Now I have two.

First, Greg, you be naïve if you think that administrative law solutions work—WC is not a good program, it is a black hole, same with SS disability, and other disabilities. No-fault results in too much generosity, kind of like public unions negotiating with politicians and public officials with the taxpayers not at the table.

One quick jab—the first patient safety study in the 70s was commissioned by the CA Med Assoc to study the benefits of no-fault. So the no-fault idea has been banging around for a long time. Troyen Brennan was a big fan of no-fault. Others, like Clark Havighurst and Patricia Danzon were in favor. I do not agree at all with Greg’s or John’s affection with administrative law solutions. WC is a disaster; disability — whether it’s VA, army, or Social Security — is a disaster. Anybody look at the rolls for Soc Sec disability people and note that they’re a tremendous burden and a lot of times the disability is very soft. Medicaid is affected a lot by SS Title 16 and 19, or whatever are the disability titles. Kids can now be on SS disability. The incentive is to compensate in administrative, non-adversarial compensation programs. Kind of like welfare rights as a governing principle or the right to medical care as political icons. Fine until the money runs out and if you like making people worthless welfare saps.

There is more than just comparing what I found in the Texas Medical Foundation study, which shows .14 % rate of confirmed quality problem as compared to 1.9% in New York.

A .28% rate over all in New York, .14 % in Texas. Understand this, TMF studies were multi layer and included interviews of the providers by committees, local and state wide.

I think that is the way to do it, not little bubble teams with an attitude, but people who have to interact with the provider.

Incidentally these PRO reviews were available for the asking—one reason I don’t accept the IOM or Harvard Patient Safety crusader researcher—if they were interested in objective robust studies, they didn’t have to do it their way.

Ok, so let’s deal with the rate of negligence, which is 0.14 in Texas and somewhat higher in the Harvard group studies, which are similar to the California Don Harper Mills study of the 70s.

Dr. Goodman says if we applied the EPA clean air act parameter for accepted risk or safety—1 in a million, no hospital could be allowed to remain open—and that is important to note, so what is the human element rate of error that is acceptable? He says it may be a goal of 1 in a million error or screw up or adverse unanticipated outcome—any of those will do.

The Clean Air Act and the EPA are not benchmarks for risk management programs or performance programs. In fact, the EPA is a joke for many reasons I won’t go into here, and their “accepted risk” is derivative of the asinine EPA and enviro fanatic governing rule — the precautionary principle. Does Dr. Goodman adopt the precautionary principle? Not likely, since he is smarter than me by half. Just doesn’t practice medicine and law at the grunt level — which forces one to know about some of these realities. So unfortunately the section on acceptable error, adverse event or negligence rate discussed in the paper is built on a bad EPA concept of accepted risk and was a bad choice by Dr. Goodman or his coauthors.

So one hospitalization involves how many potential human actions and decisions and possible errors? Anybody shoot traps—I don’t, but the best trap shooters hit almost, I say almost, 100 percent of their targets, the best ones. And shooting traps is just doing the same thing over and over, only wind or light vary once the trap launcher is set, the targets go out the same way pretty much, then you shoot ’em with the same motion.

So none of us can estimate the ways one hospitalization can produce an error, but the reason our rate of bad outcomes or adverse incidents or negligence with injury or death is less than 0.2 % is the professionalism of the people who do the work, the fail safe and backup systems that are, in fact, very good, like hospital pharmacists. However, we are just not perfect enough in the eyes of clipboard tyrants.

They always talk about air traffic and airplane safety, but I must remind you that back up and default systems and maintenance is extraordinary for the flying safety but even so there are occasional problems, and can we say that the goal is no more than one death in a million takeoffs and landings—how about aircraft accidents in military settings, where conditions and fail safes are not as complete or as effective?

I say taking care of a sick patient with a lot of other people participating is like flying in bad weather with help from people who are less skilled, while an enemy (disease) is trying to screw up the operation or plan for care.

Different set of safety considerations for elective surgical procedures, which do quite well with fail safes and safety protocols and routines. However, taking care of a sick patient is more like aircraft carrier landings at night in bad weather. My high school buddy Bill Englehart retired a Captain in charge of aircraft maintenance for the Atlantic fleet; the man loved fixing planes. He said that the carrier deck activities and operations killed one sailor every deployment for sure, sometimes more. Is that good? Yep, dangerous work, high-risk. Is it one in a million? Well, depends on how you count human judgment and actions, cumulative or summations?

In medical care circumstances and because men are mortal and fallible, what is the acceptable rate of bad or adverse or unexpected or negligent outcomes? What is a bad outcome when you’re using potent drugs and working on sick human beings who may be old or worn out? Flying in bad weather, so to speak.

See my American Council on Science and Health pub here http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pdfs/Patient-Safety-in-America-Comparison-and-Analysis.pdf, which includes tables that compare the patient safety studies. (Tables are available by themselves here: http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pdfs/Tables-from-Dunn.pdf

John Dunn

Dunn’s chart shows a summary of past studies, the occurrence of adverse events and what percent of them were considered preventable and/or negligent. However, all of these studies, including New York and Utah/Colorado, likely underestimate the occurrences. What is conveniently missing from this table are more recent studies that use the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Global Trigger Tool” method (http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/4/581.abstract?rss=1) in order to measure all adverse events (preventable or not), but which mainly focus on acts of commission, and not adverse events as a result of lack of treatment. The Global Trigger Tool guidelines provide a systematic way of examining patient records, including a minimum reviewer team (3 people), record sampling over time, and a short but rigorous review process for “trigger” events (such as a patient readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge) that deserve further review and consideration to determine whether an adverse event occurred. Because each review is limited to a specific amount of time reviewing each record, IHI admits that even their method may not detect all adverse events.

Studies that use the IHI Global Trigger Tool report a higher rate of adverse events than older studies, including the ones which we base our own estimates. For instance, a study of 1 million Medicare patients (http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-09-00090.pdf) over one month found that 1 in 7 percent experienced an adverse event, as defined by the Global Trigger Tool. Of all adverse events, about 44 percent were preventable. About 15,000 of these patients (1.5 percent) experienced an event that contributed to their deaths, an even greater rate than the New York and Colorado/Utah studies.

One could argue that a study of Medicare patients is biased upwards since they are likely to die anyway due to age-related conditions and their greater likelihood of entering the hospital compared to other age groups. But a 2010 study of 2,341 randomly selected North Carolina hospital records between 2002 and 2007 found that adverse events occurred 25 percent of the time. Of the 588 harms, 63 percent were preventable. Again, this is a far greater percentage than the New York and Utah/Colorado studies. The North Carolina study also used the IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events.

Finally, in a 2010 Society of Actuaries study, researchers examined 2008 medical claims data for “ICD-9 codes” used to identify adverse events that occur during the course of a patient’s treatment. Adverse events occurred in 7 percent of hospital admissions, nearly twice the rate of the New York study. SOA extrapolated that 6.3 million adverse events occur annually nationwide, with 24 percent of them the result of a medical error.

While Dr. Dunn may claim these estimates overstate the occurrence and nature of adverse events, it becomes almost irrelevant at this point. Something still needs to be done about the ones that do occur, and yes, they do occur and many of them are preventable. To split hairs is akin to looking at a three-story burning building and saying, “Only the first floor is on fire, thank goodness, so we don’t need to concern ourselves.”

Pamela Villarreal

Great analogy, John (Dunn):

With some patients, the circumstances are more like those that confronted the Mighty Eighth Air Force in WWII rather than today’s commercial airlines.

The clipboard tyrants (great term) need to see how well they do on a few shifts as Parkland Pit Boss.

Jane

@Greg

A correction, the rate of adverse events and negligence events using the Don Harper Mills list of sentinel events list for CA, NY and UT/CO, modified only slightly to deal with outpatient surgery in the Utah/Colorado, show no—no—change in rate of incidents or negligence. All three studies — Mills CA, Brennan NY, Brennan UT/CO — had adverse events 4%, negligence 1%, negligence with death or injury 0.25%.

That shows no crisis or epidemic and no real change in the rate of incidents. But the IOM declared a crisis, because they did something that got everybody’s attention—they projected the small study, small death by negligence rate or injury by negligence rate and projected it to hospital admissions in the nation of more than 30 million.

The deaths in UT/CO were indeed, when projected to the nation, lower. My multiplier for population of the two states to the nation in the early 90s showed negligence deaths of 25,000, but remember outcome bias inflates the negligence death numbers as Brennan admits. And in UT/CO they skipped review teams, and Brennan and his Fellow, Thomas, did the reviews for preventable and negligence.

However, another important factor for John’s project is this Global Trigger Tool, described in the Health Affairs article John referenced: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/4/581.abstract?rss=1

The authors are from the Cambridge Mass outfit on patient safety that goes back to the Harvard research. They call themselves the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). The study was of 3 tertiary hospitals, and the team they used was nurse and pharmacist and they looked for anything, and found a rate of adverse events of 33 % on a review of 795 charts.

They found 354 events with the Trigger tool, the AHRQ patient safety indicators found 35, and the hospital voluntary reporting system found 4. Cumulative events from lowest to highest E-I at the lowest level of event, E-227, F-133, G-11, H-14, I-8, and that’s on reviews of 795 charts.

The major groups of events are med related 150 (remember, a pharmacist was on the team), 109 procedure related not infectious, nosocomial inf 72, pulm DVT 17, pressure ulcers 11, device failure 6, patient falls 3, other 26.

Their conclusion is that three tertiary top of the line hospitals had a 33 percent rate of adverse events.

Another crisis, the IHI gets more funding and politicians say American medical care is expensive dangerous and needs government intervention by the smartest guys in the room.

Anybody ever notice the smartest guys in the room write the articles that declare the crisis—like the IOM or the NAS?

Guys and gals,

One thing I don’t understand in the thread above is how long comments can appear a minute apart. You don’t have time to type in that short time, let alone to think. Are these pasted in from a discussion that proceeded at a slower pace?

Interesting!

Good catch, David. This discussion took place yesterday and all these folks gave me permission to post the thread as comments today so we could share them with other readers.

I will obviously leave the discussion of the validity of the patient safety/adverse medical events studies to the doctors and the researchers, but being familiar with the “risk” business (as in insurance) I can comment on the Worker’s Comp references. Most will agree that insurance plays an important part in managing costs. The problem is that it is often overused especially in the application of health insurance.

Without trying to dispute Dr. Dunn’s primary point, I think he is generalizing regarding the performance of Worker’s Comp in the marketplace. It is only a “monstrous” problem when the enabling authorities (State Legislatures) allow gaming by the trial attorneys. Moreover it is not the concept of W.C., but the corruption in government that creates the problems. I know this because our company advocates for professionals and business owners (as well as employees)to make sure that W.C. expenditures do not become bloated feeding troughs for attorneys and employees looking to game the system. I assure you with the proper legislative support the system can work for both employers and employees. History of the various state approaches to W.C. bear this out.

Understanding that the point of John Goodman’s subject and Dr. Dunn’s response is not Worker’s Comp, I would only suggest that insurance and administrative solutions should not be ruled out with regard to possible medical liability problems (if the motivation for ruling them out is based upon a generalized misunderstanding of Worker’s Comp performance).

It seems clear that insurance is needed here because unexpected and unwanted medical outcomes are inevitable regardless of fault. It is also clear that a system must be in place to control “rent seekers” legally, and to administer payments without bias. Whether that entails the use of the “No Fault” model or something else is the debate, but there seems to be no question (as Greg Scandlen notes) that the worst alternative is placing the outcome in the hands of the judicial system. Worker’s Comp experience tells us this.

A good assessment. 10 years ago, the Institute of Medicine came out that an estimated 100,000 people died yearly of problems that were correctable. Your assessment goes further and looking at the whole picture comes up with frightening figures. As someone told me that a hospital is no place to be if you are sick. And to think that there are best practice guidelines how to avoid medical errors, and how little attention is embraced by the provider and the hospitals in which they practice. It would be wonderful if we could make it work, by employing knowledgeable reviewers and avoid the bureaucratic bull shit that hampers that initiative. remember Kramer’s rule of 6 to remove all of the shortcomings that our system now has. Contact me if you need my polyanish assessment once more.

Dr Bob Kramer

With respect to the no fault piece–before making a recommendation of automatic compensation, I think it is important to explain why nofault auto insurance regulations ended up increasing costs. One must also explain how the proposed hospital compensation system will create a different result.

It is also essential to deal with Jane Orient and John Dunn’s comments–how is a review board going to help when the metrics are basically nonexistent and therefore whatever the ideologically motivated “clip board tyrants” say they are?

My sentiments and experience are with Dr Dunn and Dr Orient. I have admired the columns by Mr Goodman for a long time. I have quoted him often. This current column is way off base. The IOM studies were so flawed and yet the numbers were so sensationalized in the media without question. They are repeated often and it brings to mind the saying that a lie repeated often enough becomes the truth.

I also have a concern with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement studies. Although they are a not for profit the principals make generous salaries pointing out the flaws in the health care system and then consulting to “fix” them. There is bias and that goes undisclosed. Their Trigger tool, as far as I can determine, is not validated but is assumed to be the “gold standard”. where are the validation studies?

@Linda

Linda, are metrics necessary if a no fault system is used? Aren’t we talking about separating the determination of liability from the “damages” reimbursement? The goal would be to protect doctors and facilities individually from huge damage awards.

Your question of “no fault” increasing costs is a valid one, although it is possible that auto liability and medical liability are not totally compatible in terms of risk models.

There would be many fewer reported hospital fatalities if the many thousands of nursing home patients who should be placed in hospice were not admitted to an acute care facility. These numbers are much less when charts are reviewed individually rather than using aggregated computerized data.

Frank, without a metric of harm how is one going to decide whether someone determines compensation?

In auto accidents one generally has at least some kind of crunched car and even then there is debate over the extent of injury. Whiplash? Bad back? Really?

Judging from the results, the adversarial system is better at controlling the faking.

The problem is that medical harm is even murkier than harm from an auto accident. Was the poor birth outcome really the fault of the physician? Did the infection come from the hospital or did the patient have it when admitted? We need clear metrics to define harm as well as fault.

John

After I the IOM released data from their original report I told people we should stay out of hospitals and die at home.

This data is fine for info but is not relevent as to the daily hospital mortality.

There certainly are inappropriate deaths and complications in the hospital but there is no study as to discern hospital vs no treatment, which would be a double blind study (not doable with a review board)

There is certainly a move by the nursing homes to not do hospice care and allow people to die there, they get transfered to the hospital.

If you lood at the adversre event studies – probably greater than 95% are relatively meaningless. There are certainly major events. The majority should be studied as system problems, and give system improvement ideas.

we have lots of room for improvement in the current system. Many are working hard at that. It is far from simple as many of you think. At our hospital we have been working for two years to get 100% appropriate antibiotic use preoperatively and fail at the 99% level. That last 1 % is tough. You would think this is a no brainer – but all the orders are written, the system is in place, and the drug is delayed from the pharmacy or some other useleess excuse. Amazingly complex system that we all think is simple.

Good Luck

Mark Fahey, MD

@Linda

Sorry Linda, I was assuming your reference to metrics concerned the relative performance of the medical providers to establish norms etc. I am sure I am viewing this in an overly simplistic manner, but I was thinking that it wouldn’t be all that difficult to determine whether or not negligence is involved in bad outcomes based on some common sense premises.

I realize that notion may seem pollyannish, yet I don’t see why clear definitions of negligence are beyond our common sense capabilities. The problem with the “adversarial” approach is the inevitable waste of resources due to attorney fees and court costs. And, how often can we claim justice has been served in tort cases?

The airline industry is often held out as a “good example”, but an aspect that is not often mentioned in these discussions is the poor financial performance of the airline industry as a whole and the major failures it does suffer when “new” dangers arise, such as 09-11. (Has the TSA improved safety and efficiency? Can we even imagine that it can meet some “pay for performance” measure? What about the current focus on air traffic controllers? Is this a “new” development? Not likely.)

I am not suggesting that profitability is the purpose of health care, only that this significant piece of the government expenditure will require financial accountability.

And, what if H1N1 had been a major killer? Our healthcare system had serious trouble without people dying in the streets, which we were fairly certain would not happen since it was not seen to happen in Mexico City. Yes, there are “cultural issues”, gaming, etc; and yet, an honest person who has to pay cash and is willing to do so, will almost always pay more than any other “buyer” in “organized” health care, which is the opposite of almost any other business in the world. I did a long shift today in a community hospital in a small community that is struggling with these issues every day. Everyone who shows up there to work, does their absolute best under the circumstances. Does anyone think that there is any significant percentage of places where people show up to do less than their best, intending to do less than they can? Of course not.

Thanks,

Stephen Nichols, M.D., a practicing physician in a community emergency department

Steve,

Ever worked in a U.S. Government Facility?

Bill Bass, MD

@Stephen. My best friend worked in a nursing home for 20 years. And according to her, yes, there were people who showed up and did less than their best. Maybe it was not intentional, but it was certainly careless. The biggest problem was charting correctly, but my friend often had to try to interpret vague descriptions, and wrong medications listed due to slight misspellings. These types of things can put a resident’s life in danger. In the area of preventable adverse events, there is certainly low-hanging fruit that can be picked.

I don’t think anyone disagrees that even one preventable error is too many and that every effort must be made to minimize adverse events.

It is interesting to note that John’s pie-chart specifies that of all adverse events – preventable but not negligent, malpractice, and “other,” only 27.6% of these events were listed as being the result of “malpractice.”

It doesn’t matter which set of numbers we use to determine the percentage of adverse events as compared to actual malpractice which occurs in America’s hospitals – because no matter what set of numbers we use, the ONLY people who profit from the status quo will use those numbers to prove that doctors and hospitals are criminally negligent and have to pay (mostly lawyers, but that’s another issue.)

As recently as last week, personal injury lawyers here in Pennsylvania who oppose any reforms to our existing system of medical “justice” were out in public announcing YET AGAIN that 98,000 die every year because of medical mistakes – and THAT’s why we shouldn’t adopt any reforms to the current system.

It doesn’t MATTER to them that the data set from the IOM study has been thoroughly debunked. It doesn’t matter to them that the IOM piece pointed more to system failure than individual negligence as the underlying cause of adverse events. It doesn’t matter to them that the IOM’s number of deaths from errors wasn’t really a hard 98,000 but a RANGE that began at fewer than half that amount, 44,000.

The only thing that matters to them is that they can tell audiences which don’t know any better that bad doctors and hospitals kill more people every year than, gasp, BREAST CANCER. Or that medical mistakes kill more people every year than a jumbo jet crashing every day, gasp! They’ve adopted the number as if Moses brought it down from Mount Sinai, and the ONLY THING that people who know better can do is to keep debunking it OVER AND OVER AGAIN – as Dr. Dunn has been forced to do here. (BTW, thanks for the additional data and ammunition.)

Knowing that trial lawyers will do or say anything to protect the contingent fee bonanza and their full participation IN that bonanza, what’s needed is for medical professionals and policy makers who sincerely want to protect patients while keeping doctors and hospitals in business to come together in support of a plan which removes medically ignorant jurors (not an insult, simply a statement of educational fact) from the equation.

It is simply not possible to teach an average American citizen enough medicine in a single week’s trial for him or her to make the RIGHT decision as to a health care provider’s level of competence or negligence. It takes a doctor upwards of 11-15 years to be qualified to make a medical decision that impacts a patient’s life. Alternating lawyers’ arguments and dueling medical “experts” and conflicting witness testimony cannot possibly provide enough objective data for a correct decision – particularly since the people making the decision need to be taught the basis for every aspect of the medical treatment involved in the suit. They couldn’t learn enough medicine in a YEAR to make the kind of objective medical decision courts expect of them.

So how do jurors decide? They CHOOSE whether or not they believe the plaintiff’s or the defendant’s lawyer and expert witnesses. How do they make that choice? Maybe the defense attorney speaks more clearly. Maybe the plaintiff looks more sympathetic. Maybe the defense witness seems more credible. Maybe the doctor seems like a really nice, caring guy who wouldn’t hurt a fly. Maybe they don’t like the plaintiff’s lawyer’s tie. But for one reason or another which has nothing to do with objective medical knowledge, the jury will decide who’s telling the truth, and that’s how they’ll rule.

The current system is now and always has been a virtual popularity contest between lawyers and expert witnesses – and which benefits lawyers on BOTH sides. It benefits legitimately injured patients rarely and unfairly (they receive roughly 46% of settlements and awards after costs) and benefits doctors and hospitals not at all, particularly considering that 90% of medical liability court cases are found FOR THE DEFENSE.

What’s needed is a system in which the people making decisions on who did what wrong and who should or shouldn’t be compensated actually KNOW something about medicine, so that they don’t need to be educated from scratch and so they have a reasonable certainly of making the right decision.

Sadly, personal injury lawyers will use debunked data like the IOM study and anything else they can find to terrify the public that their doctors and hospitals are going to kill them, and that they, the LAWYERS, are the only thing between doctors and death.

So as long as there’s a sensational headline for them to grab onto, they’ll use it as yet another reason NOT to reform a completely dysfunctional system. The IOM report is just one weapon they’ll continue to use to resist positive change, so it is particularly incumbent upon those who SUPPORT those changes to make sure that any data WE release is unimpeachable.

Hopefully, this newest data set won’t be used for the same purpose – although I fear that it will.

“I sent him a paper I wrote for the American Council on Science and Health . . .”

There goes any credibility you may have had.

I will right away snatch your rss feed as I can’t find your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly permit me recognise in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.