Consumer-Driven Health Plans Could Save $57.1 Billion per Year

The RAND researchers we reviewed before have come out with a follow-up study in Health Affairs of the potential impact of consumer driven plans on the American health care system. This is “Growth Of Consumer-Directed Health Plans To One-Half Of All Employer-Sponsored Insurance Could Save $57 Billion Annually,” by Amelia M. Haviland, M. Susan Marquis, Roland D. McDevitt, and Neeraj Sood.

Most of the media reports have been reasonably accurate, see The Hill and The Washington Post, but have missed the real potential in the study.

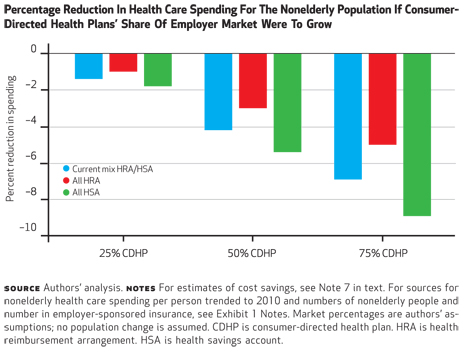

The media reports have focused on the study’s conclusion that if half the people with employer-based plans were in a consumer driven plan, the system-wide savings would be $57.1 billion. But this is a mid-range estimate that assumes an equal mix of HRA and HSA approaches. The study acknowledges that HSAs are far more cost-effective, and estimates that, if all of these people were in HSA plans the annual savings would be $73.6 billion.

Now that is a pretty big chunk of change, but even it likely underestimates the impact. The study’s authors write:

This estimate was based on cost reductions in the first year of consumer- directed plan enrollment and did not assume any reduction in cost trends for these enrollees.

First year savings are the least of it. The real value of consumer driven approaches is that trend is reduced and the savings mount up over time. The 2009 study by the American Academy of Actuaries, for one, found that the trend over time for CDHPs ranged from 12% to 17% lower than for traditional plans. (By the way, this new RAND study is one of the very few, if any, to cite the AAA study as a source.)

This difference in the experience of HRAs and HSAs is particularly important because this study relies on data from 59 large employers from 2003 to 2007. HSAs were signed into law in December 2003, and didn’t really go into effect until 2005. So the HSA experience studied here must have been very limited.

Importantly these savings do not accrue solely to employers. The study looks at out-of-pocket costs as well as premiums, and concludes that families themselves reduced their costs by over 20%. The authors write:

Savings derived from switching to consumer directed health plans could benefit both employers and employees. Inflation-adjusted health care costs have increased more rapidly than real wages in each of the past six decades. Reducing health care costs can boost output, income, and employment growth in US industries that provide employer-sponsored insurance to a large percentage of their workers.

So the savings are real and substantial, but what are the problem areas? The authors looked at several.

Are these savings due to selection? No, the authors controlled for that. They write:

Consumer-directed enrollees in these large employer plans spent less on health care than enrollees in traditional plans even in the year prior to their enrollment, and the estimates above controlled for this favorable selection into the consumer-directed plans.

Are “vulnerable populations” (high risk and/or low income) disadvantaged? They don’t seem to be. While “nonvulnerable” families decreased spending by 20.9%, those with low incomes reduced spending by 17.3% and those with chronic conditions reduced it by 14.7%.

Do people cut back on necessary care? Here it is hard to tell. Inpatient care dropped by 22.1%, outpatient by 18.2%, and prescription drugs by 16.0%. The drop in preventive care was much less, ranging from 2.7% to 4.7% for six different procedures. The authors note that prevention was fully covered in all these cases, so:

… Ongoing communication with plan enrollees may be necessary to improve their understanding and use of preventive service benefits.

They add:

One objective of consumer-directed plans is to encourage greater consumer shopping for health care. Our findings that reductions in spending occur through lower spending per episode, more use of generic versus brand-name drugs, less use of specialists, and lower inpatient hospitalization suggest that these plans do induce changes in treatment choices and not just access. Further research is required to determine whether these are appropriate changes, and our findings concerning preventive care demonstrate that more information is needed to improve consumer decision-making.

Once again, these authors have done some excellent research and we hope they continue this work. In particular, it would be very useful to find out more about the effects over time (how is trend affected?) and how effective are various forms of employee and patient education, support services, and access to information.

One of our main contentions has always been that people will navigate the system better as they become more accustomed to it. It would be useful to test that theory in real-world conditions.

Perhaps most importantly, this kind of quality research may persuade the so-called “research community” to finally put aside their partisan opposition and begin to take this trend seriously. It is the future of health care.

The rule of thumb is that consumerism (i.e. high-deductible plans with higher cost-sharing) could save about 30% of the cost of medical care. The RAND Heath Insurance Experiment (HIE) found this, as did a RAND study from last year. This is significant. However, I wonder if high-deductible plans couldn’t save even more. If doctors and hospital got in the habit of quoting prices because customers are price-sensitive, there might be spillover effects to the higher cost, impatient areas. If there was a way to remove much of the bureaucratic hassle of paying and tracking small claims, there would be more resources available to better managed the large claims. Providers have little incentive to justify prices in the current environment of third-party payment. As a result, prices bear little resemblance to costs. The RAND HIE identified what could be done in the current system with higher cost-sharing. I wonder what could be done if all consumers had a high-deductible plan and health care providers had no institutional memory of a time when consumers were not price sensitive.

great post. I bet it takes a while for those in the “research community” to see the trend.

Yes, it is true that the first year savings may only be the tip of the iceberg of potential savings, but it is equally true they may not be sustainable, as the researchers also noted a sizable portion of people enrolled in these plans may have postponed necessary care and even preventive care. The impact of these decisions could potentially raise the cost of care in future years.

That said, it is worth continuing to track the long-term effects of HRAs and HSAs while also seeing if their prevalence can actually influence providers to be more forthcoming with their pricing.

After all, what good is “consumerism” if it is hard to effectively comparison shop?

$73.6 billion provides a very compelling basis for action! Consumer empowerment is a great cost-saver that increases both the efficacy and efficiency of health care.

Good morning John,

America is lurching toward more consumer participation in health care purchasing, but it is doing so for the wrong reasons and for the wrong beneficiaries. Health plans are pushing consumers to pay more and more for health care through higher and higher deductibles for less and less coverage, all the while escalating their premiums. With or without a Supreme Court ruling on the health care reform act, we are headed toward a society in which most health insurance will be a skinny Oreo layer of coverage that will not cover low-level medical expenses and will cut out before paying for catastrophic care, leaving every American one banana peel or one diagnosis away from medical bankruptcy.

The principal beneficiaries of this narrowly underwritten health coverage, of course, are the health plans, not the people. This is not to blame health plans, who are simply trying to operate in a wholly irrational market.

The only way to bring rationality back to the market is to reset health care pricing in economic terms everyone can understand and agree upon. Why should the price of an appendectomy vary by tens of thousands of dollars in California–even within the same hospital?! Because we let it.

The PPA was formed to help communities rationalize pricing while maintaining and improving health person-by-person, community-by-community. So as we head inevitably toward much more consumer participation in health care payments, the PPA will be there to help organize and guide the market reorganization by giving patients and providers a voice and a program of direct action that can reduce costs and improve health.

Cheers,

Charlie Bond

Greg, perhaps part of the challenge with the “research community” is the funding of the research. There are plenty of rent seekers heavily invested in the anti CDHC model (let’s call it “managed” care) that are not at all interested in an informed public able to navigate the healthcare system through their own means.

Moreover, this debate over the healthcare models is really just a continuation of the overall political war between the entitlement crowd and the free market supporters.

In terms of healthcare, it is really not a winner take all conflict. Rather it is a philosophical battle to determine if our system is to primarily be a top down managed system with “bones” meted out to CDHC (the old MSAs are an example), or if it is to be primarily a consumer directed system with safety nets for outliers.

It seems the political approach should be that we have tried the top down management approach for decades (in various forms), and the financial numbers speak for themselves. Why don’t we try a different approach to solving the problem?

Charles Bond, can you explain the “PPA”?

“With or without a Supreme Court ruling on the health care reform act, we are headed toward a society in which most health insurance will be a skinny Oreo layer of coverage that will not cover low-level medical expenses and will cut out before paying for catastrophic care, leaving every American one banana peel or one diagnosis away from medical bankruptcy.”

I don’t understand your comment the coverage will “cut out.” In my experience these plans combine the high deductible with catastrophic coverage (high or unlimited maxs). Where is the cut out?

Sorry, my question is addressed to Charlie Bond, not the author.

Our real world experience with 20,000 employer groups shows the same results. HSA-compatible plans work both year over year and in helping families build health savings for the long term. This should surprise nobody.

The biggest effects of these products will come as they force the market – carriers, payers, employers – to build the kind of feedback loops that we take for granted in other sectors. Price transparency will come from the bottom up (it is the top that has prevented it thus far) as individual firms see economic interest in doing it.

Thank you Greg for highlighting the research.

I that in the earlier CDHC options many dismissed or

devalued the viral way in which consumers share their positive and negative health care experiences and expenses

our lives today force us to engage with friends family service providers and business colleagues and this trend is growing among multiple age demographics and behavioral and financial demographics and this will continue to impact the growth of consumer directed health options and consumer adaptations.

thanks again for sharing the article and research summary

Greg – I have gone to the original article and associated technical appendix to get a better feel for the conclusions you are taking from the new Rand related Health Affairs piece. Suffice it to say that there are, in my view, material open actuarial issues with the study, most of which are similar to any reliance on your also referenced American Academy of Actuaries “study,” which I have previously pointed out is only a survey of available literature and hardly qualifies as a study in its own right. At any rate, all the underlying data for both of these papers are somewhat dated now, and neither deals with the fundamental problem involved with attempting to evaluate the true, long term impact of HDHP on health care costs – the fact that it is impossible to “enter the same stream twice” (always the problem with testing human behavior), and the longitudinal issue – none of these studies have or probably can track a five year or longer experience for the health care costs of people under such programs that doesn’t inherently contain its own bias. I certainly believe that CDHP/HDHP programs can squeeze out a great deal of unnecessary care – one time – but the real impact on the system can only come if providers are compelled to compete on a rational price basis (which will lead to quality competition as well), and that is the best contribution that these kinds of plans can ultimately make, because the consumers will demand and deserve to have such a market system to operate in.

‘No one spends other people’s money as wisely as their own.’

Winston Churchill was speaking of gov’t money, but the same applies to insurance company $$ vs my own.

From the study.

“. We project that an increase in market share of these plans—from the current level of 13 percent of employer-sponsored insurance to 50 percent—could reduce annual health care spending by about $57 billion. That decrease would be the equivalent of a 4 percent decline in total health care spending for the nonelderly. However, such growth in consumer-directed plan enrollment also has the potential to reduce the use of recommended health care services, as well as to increase premiums for traditional health insurance plans, as healthier individuals drop traditional coverage and enroll in consumer-directed plans.”

Steve

H.D. Carroll —

All of the vendor reports (from Aetna, CIGNA, the Blues, etc) indicate these plans reduce trend substantially. This is borne out by employer surveys. Granted these are not academic studies, but they may be more reliable and certainly more timely than such an academic study.

The AAA paper is actually better than you suggest because it circles back to prior papers it published that raised issues that are now being answered. For instance, in earlier work AAA was skeptical that employees would reduce spending because they wouldn’t see the money as their own. If employees saw the money as employer money they would be less likely to conserve it. That concern is now being answered and it is a large part of the reason HSAs are more effective than HRAs.

As I said, this RAND study is limited because it uses only one year’s experience. Other information suggests that people do indeed change behavior as they stay with the program and learn how to navigate the support tools.

I agree entirely that providers need to start offering real prices and compete on that basis. Market penetration is what will force this.

Greg,

I’m curious why you believe that data provided by health plans (who have a vested monetary interest in supporting a model that fills their coffers more efficiently), may be “more reliable” than an academic study?

Seems to me “disinterested” parties are best at this work, and I hardly see the Aetnas, Cignas and Blues of this world as disinterested.

Chris: You’ve got it exactly backwards. The companies you listed were latecomers to the CDHC market, would have preferred traditional insurance, were they not forced to adapt, and make more money off of traditional insurance.

If buyers cut their premiums by one-third and put the savings in a Health Savings Account, that means the insurance company’s revenues have been cut by one-third. Ditto for brokers commissions.

So, no. The insurance industry does not have a self-interest in promoting CDHC plans. Quiet the opposite.

I have been pushing for consumer driven plans from the time I joined TeleDoc almost ten years ago. And the attractive part that I supported was that if the patients stayed healthy and follow their doctors example, by rolling over any surplus at years end could roll it over into the next year. If this scenario persisted, that for many they could fund their retirement. So it is a win-win situation; patients wanting to stay healthy, cost savings for the employer, reduction in the cost of care, and the ability of the doctors the chance to practice the kind of medicine they were taught. There is huge opportunity to practice elegant medicine, reduce the number of expensive testing, as the incentive to do so is lost. The fee schedule must be changed so that the doctor who is able to have a more compliant roster, can and will profit in the end. The economic model that should be espoused is the realization that the very best care, not necessarily ordering the most expensive tests, in the long run is the most cost effective. To avoid the “re-do” saves hundreds of millions of dollars; the patients have a compassionate healer who is reimbursed not on the basis of how quickly he can turn patients in and out, but by the extended good health, with adequate time to think, to treat patients in the very best way, regardless of the cost because a longer time reviewing the history of an episode, the best medical approach to make the proper diagnosis, and order only those tests to corroborate one’s clinical diagnosis, and not as we are doing now by taking an abbreviated or non existent history and a shortened physical exam and ordering the most expensive tests and make the diagnosis by using these tests to make the diagnosis and then have the physician be a hero. We were all taught in medical school they the most important steps were to 1) take a detaied history, 2)do a complete physical and not ausculting the chest and heart without having the patient remove the cloths fully so that the doctor is plying his craft, the patient has a sense of thankfulness that he or she are being treated the way they should be. My Dad was an internets and told me over 50 years ago, that if you listen to a patient they will tell you exactly what is wrong 80% of the time.

That’s all for now. Next I want you to address the importance of primary care and how with modifications can become more importantly the saviors of healthcare. Have you ever thought of gathering several of us physicians to share a round table discussion of how we implement change. Many doctors are leaving their practices to become “concierge” doctors, which will allow them to practice medicine properly. I am not sure if the expense precludes most folks who can’t afford it. $20,000 A YEAR IS MORE THAN MOST AVERAGE FOLKS CAN AFFORD.I guess if one wants to have only wealthy patients who stay well is OK, I guess driving a Lamborgenie, while others are driving Kia’s, is OK if you can afford it. Medical tourism is another efferent to our system. The very wealthy foreigners come to the US with bags full of cash because the care here, when you can afford it is the best in the world, Traveling to Bankock, Buenos Aires under the guise that better medicine is there, it is only because the expense here is too high.

Enough for now.

Dr. Bob Kramer.

Chris, let me add to John’s comment. Academic studies are always retrospective. By the time the study is proposed, funded, designed, implemented, and published, five years have passed. This is of no value whatsoever to a business doing strategic planning.

Business studies are designed to get information quickly so they can revise products NOW. Their purpose is not to influence public policy but to direct their product design and marketing efforts. They need to know what works and what doesn’t. If they manipulated the results they would be screwing themselves.

Bias would be far more likely in an academic study where the authors are more likely to have a political agenda.

Greg,

With today’s HDHP products 4% savings makes sense as the study notes due to more careful utilization in a full replacement situation. I don’t buy the study’s extra remark about the fallout from reduced utilization. The next step in health care consumerism is reference based product offerings. If they are on the hook for the increment above the allowance folks will shop. In today’s world consumers don’t care how much of the insurers money they spend above the deductible. If we do this then I think we’ll see the 30+% of the old Rand study, not to mention the benefits of a health care marketplace forming.

Steve,

The 4% referenced was for total system-wide costs if 50% of employees were in HSA/HRAs. The saving to those people is on the order of 30%. But that leaves out Medicare, Medicaid, the uninsured, and half the employer market. So they are saying if @one-quarter of the population saves @30% (especially a less-expensive quarter), the total would be 4% of the whole.

Steve, you are absolutely right in that the patient must have “skin in the game” in order for the plan to realize cost efficiency. The trick in the plan design is to recognize that magic point along the curve in which the patient (or patient advocate) loses effective (realistic) control of the medical course of action.

Put another way, the CDHC plan should be designed so that insurance becomes involved at the point in which effective self management has been minimized – not too soon and not too late. This can be done a number of ways, but the simplest methodology is the use of co-insurance (not copays).

Greg, I don’t think savings is even close to the 30% because today’s products don’t allow for balance billing on 90+% of providers vs. the plans of over 30 years ago. When a rich plan is offered as an option to an HDHP the allowed amount for the HDHP (employer claims + employee share) is generally about 1/2 of the richer benefit plan. There is significant selection going on where typically 20% (the best risks) migrate to the HDHP. Things would change dramatically if people were on the hook for 100% of the premium (almost everyone would buy an HDHP). A very large employer going to full replacement HDHP is a good study, but even then poor risks might migrate to a spouses richer plan.

Thank the Lord for small favors. I am having trouble even writing about the study in Consumer Driven Market Report because it is so flawed: (a) the control group is “traditional” coverage ending in 2007, so it ignores 5 years of rising deductibles recently outside the CDH account design that are certainly “high deductibles,” rendering the entire research model invalid, (b) it assumes that PPACA will stimulate growth in CDH accounts based on a 2009 analysis that was proven wrong (and even cites MLRs of as an example!), and (c) the findings about preventive benefits are obviously dated. Otherwise, it’s a good study. And it definitely comes to the right conclusions.

Bill,

Of course it is dated. That is the point I made above about academic studies — they always are looking five years into the rear view mirror. Still, to the extent it compares conditions at the time of the data collection, it is worthwhile for policy people. Very few policy types would have expected these kinds of results at the time. Perhaps they will be less smug going forward.