Connected Care: Moving (And Keeping) Patients Out Of Hospitals

(Part one of a two-part series. A version of this Health Alert was published by Forbes.)

(Part one of a two-part series. A version of this Health Alert was published by Forbes.)

One of the greatest frustrations in health care is that technology tends to drive up costs. In pretty much every other area of our lives, technology reduces costs. Increased health spending is associated with better health outcomes (as recently summarized by Cynthia Cox of the Kaiser Family Foundation). Nevertheless, we would like to get these benefits at less cost.

The opportunity to achieve this is at hand. A host of technologies promises to significantly reduce costs by eliminating friction in the flow of clinical data between providers and patients, making sense of data from different sources, and allowing patients and providers to interact in new, cost-effective ways. This will allow patients to get more care where they want it, and not where the system demands they show up.

The best way to describe this new environment is “connected care.” However, these technologies threaten the status quo in ways that incumbent providers and tried-and-true ways of doing business will resist or twist beyond recognition unless the incentives are properly designed. Experience thus far suggests cautious optimism.

The federal government has performed poorly in the first stage of this transformation to connected care: The interoperability of Electronic Health Records. Uncle Sam has spent almost $30 billion since 2009 to induce hospitals and doctors to deploy EHRs that were supposed to be interoperable (in other words, to talk to each other). They do not, which is largely due to perverse incentives in the federal subsidies.

That money is now spent, so the federal government’s ability to interfere in the development of connected care has shrunk. Nevertheless, challenges remain. Connected care promises to move more care out of institutions and into (or near) patients’ homes. This threatens inpatient facilities, which had previously thought they were going to profit mightily from the Affordable Care Act. However, HCA reported that uninsured volumes increased almost 9 percent in the second quarter versus a year earlier, and uninsured patients’ hospital admissions continued as a theme in the third quarter. Speaking at the Wall Street Comes to Washington Roundtable on November 17, Sheryl Skolnick of Mizuho Securities USA Inc. noted that investors seemed surprised to learn that the Affordable Care Act had not actually led to 100 percent universal coverage!

Congress has also started to nibble at hospitals’ ability to manipulate Medicare’s fee schedules to ensure excessive reimbursement. Hospital outpatient facilities look similar to physicians’ offices, but hospitals can charge more for procedures. Congress and the President just agreed to eliminate the excess payment for new outpatient facilities. Hospital prices have risen by 5.1 percent more than the Consumer Price Index over the last twelve months, so this is a small but significant step in the right direction.

Technologies that reduce the need to hospitalize patients should reduce overall health costs. However, new payment mechanisms also threaten other inpatient facilities. A couple of years ago, Medicare launched a series of Bundled Payment Care Improvement initiatives, which make providers financially liable for a longer period of care than usual. For example, a hospital will bear risk for the total cost of treating the patient for 30, 60, or 90 days, instead of just the hospitalization.

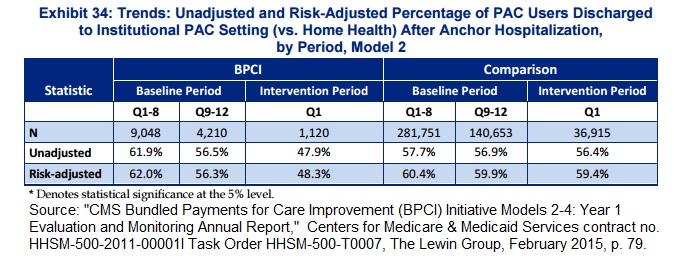

Paying hospitals this way appears to motivate them to discharge patients to lower-cost venues. One of the initiatives led to a significant reduction in the proportion of patients discharged into post-acute care institutions (skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, or long-term care facilities) versus going straight home with home-health assistance, in the first year. For the first eight months of the 12-month baseline period, 62 percent of patients were discharged into post-acute institutional care. The proportion dropped to 45 percent after the policy took effect (see Exhibit 34 of the consultant’s report, below).

However, those discharged straight home were not just given an aspirin and a pat on the back, but also assistance at home. Connected care – including telehealth, wearable sensors, smartphone apps, and other technologies – is on the verge of enabling much more care to be delivered at home, at much lower cost.

The promises of and obstacles to this new era of connected care will be the subject of the second part of this series.